Lysergic landmark gets stereo/mono remaster treatment... It isn’t easy to pinpoint singular, watershed moments in a culture’s evolution – in fact, it’s a messy business, heroes and hucksters alike laying claims to history. But it is safe to say that when Electric Music For The Mind And Body arrived via Vanguard on May 11, 1967 – six weeks ahead of the fabled Summer Of Love – the pop landscape had seen nothing of its kind. Bursting forth as if it could hardly hold Young America’s collective, bottled-up repression and restlessness a second longer, Country Joe & The Fish’s super-charged debut was a game-changer, a one-of-a-kind artefact, projecting a hippy “new normal” out to an almost uncomprehending world. While certain mega-popular recording artists danced around the notion of mind expansion via recreational drug use circa 1965-67, the Fish came right out with it. “Hey partner, won’t you pass that reefer round,” singer Country Joe McDonald moaned in “Bass Strings”. In the daring “Superbird”, the Fish harboured the suggestion that Lyndon Johnson retire to his Texas ranch and, oh, drop some LSD. And then things got really weird without any lyrics at all in “Section 43”, a virtually indescribable swirl of fog and sound, a psychedelic masterpiece assembled in movements, that simulated an acid trip. “I liked the music full of holes,” McDonald said recently, “as opposed to a wash of sound.” A product of the radicalised San Fran/Berkeley mix of progressive politics, youth culture, the Beats and anti-war protests, Country Joe & The Fish (singer/writer/guitarist Joe McDonald, guitarist Barry Melton, keyboardist David Cohen, bassist Bruce Barthol, drummer “Chicken” Hirsh) evolved from McDonald’s solo talking-blues coffeehouse sets into a full-blown, even-the-kitchen-sink electric band circa early 1966. Two DIY-style EPs, the second of which included a trippy early version of “Section 43”, were grassroots hits. Under the production tutelage of musicologist and folk/blues wunderkind Sam Charters (whose original stereo mix-down appears here), though, the Fish poured their chaotic all into Electric Music, (arguably) outgunning the celebrated psychedelic frontiers represented by the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Musically, the Fish revolved around Melton’s blistering, raga-like guitar runs – which sparred with McDonald’s vocals – and Cohen’s buzzsaw Farfisa leads, which took Al Kooper’s keyboard work with Bob Dylan to an electrifying extreme. Their ostentatious approach is so varied, though, that high-minded analysis is useless. Blues structures collide with unconventional time changes, classical composition blends with backwoods harmonica, straightforward folk/rock morphs into baroque improv, jazz/world music undertones float by – Electric Music came at listeners from myriad angles. Lyrically, the Fish were provocative, outrageous, absurd. Politically strident, yes, but their protests, like the scathing “Superbird” – Melton’s wildfire guitar front-and-centre – carried plenty of good-natured, common sense humour. Their aural acid trips, a Fish specialty in the early years, are infused with grandeur and exploratory wonder. But they could be darkly fatalistic, too, as on the feral “Death Sound Blues”. From the hyper-blues riffs opening the tumbling rollercoaster “Flying High”, Electric Music transcends the polite coffeehouse fare often passing for 1960s folk/rock. McDonald’s wry, wide-eyed vocal approach is perfectly apropos here, and even better on “Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine”. A character sketch of sorts, a romance gone awry, it leaves boy/girl, moon/spoon pop fare in the dust, its unconventional rhythms and surreal storytelling making it the album’s most compelling track. There were less-distinguished moments: “Sad And Lonely Times”, pleasant as it is, aims for a Byrds-style melding of psych and country, and misses the mark; “Love”, more-or-less straight boogie, gets by on some intricate interplay. But it’s an inadvertent preview of the moribund soul/blues workouts that would eventually sour the San Francisco scene. But “The Masked Marauder” and “Grace” close out Electric Music amid some of the more outré recesses of early psych. The former, another of the group’s dizzying patchworks, traverses a cycle of spacey keyboards, childlike chants and bluesy harmonica – a band showpiece. On the latter, written for Grace Slick, they opt, for once, for some studio trickery – bells, chimes, water sound effects, reverbed vocals – an enchanting work of no small mystery. EXTRAS: Original mono mix – not heard since the late ’60s – extensive photos, reproduced posters, liner notes by Alec Paleo, and reminiscences from many principals, including Country Joe McDonald and Barry Melton. Like Torn Q+A Country Joe McDonald What were some of the influences in this record? R’n’B from my teenage years and C&W; cool West Coast jazz… some semi-classical stuff. I was a big fan of John Fahey and he probably influenced “Section 43”. All the songs were written by me on my guitar with harmonica. “Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine” has a very unusual sound. How did that one come about? It just popped into my head one day. It is odd because it has a verse, chorus and bridge. It is of course blues-based, but not a blues as such. The guitar parts and organ give it a unique sound. Also Chicken and Bruce gave everything a very distinct drum and bass bottom to the songs – not typical of rock or blues bands. How did “Superbird” go over back then? Was it censored from radio? I don’t remember anyone ever objecting to “Superbird”. Of course there was hardly any radio for us to get play on back then. Just progressive FM stations and very few of those. I think we put it in our shows all the time because it had a nice beat and seemed like a regular R’n’B song. INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN

Lysergic landmark gets stereo/mono remaster treatment…

It isn’t easy to pinpoint singular, watershed moments in a culture’s evolution – in fact, it’s a messy business, heroes and hucksters alike laying claims to history. But it is safe to say that when Electric Music For The Mind And Body arrived via Vanguard on May 11, 1967 – six weeks ahead of the fabled Summer Of Love – the pop landscape had seen nothing of its kind. Bursting forth as if it could hardly hold Young America’s collective, bottled-up repression and restlessness a second longer, Country Joe & The Fish’s super-charged debut was a game-changer, a one-of-a-kind artefact, projecting a hippy “new normal” out to an almost uncomprehending world.

While certain mega-popular recording artists danced around the notion of mind expansion via recreational drug use circa 1965-67, the Fish came right out with it. “Hey partner, won’t you pass that reefer round,” singer Country Joe McDonald moaned in “Bass Strings”. In the daring “Superbird”, the Fish harboured the suggestion that Lyndon Johnson retire to his Texas ranch and, oh, drop some LSD. And then things got really weird without any lyrics at all in “Section 43”, a virtually indescribable swirl of fog and sound, a psychedelic masterpiece assembled in movements, that simulated an acid trip. “I liked the music full of holes,” McDonald said recently, “as opposed to a wash of sound.”

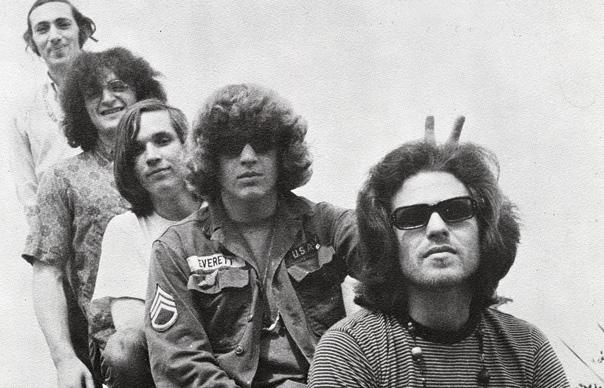

A product of the radicalised San Fran/Berkeley mix of progressive politics, youth culture, the Beats and anti-war protests, Country Joe & The Fish (singer/writer/guitarist Joe McDonald, guitarist Barry Melton, keyboardist David Cohen, bassist Bruce Barthol, drummer “Chicken” Hirsh) evolved from McDonald’s solo talking-blues coffeehouse sets into a full-blown, even-the-kitchen-sink electric band circa early 1966. Two DIY-style EPs, the second of which included a trippy early version of “Section 43”, were grassroots hits. Under the production tutelage of musicologist and folk/blues wunderkind Sam Charters (whose original stereo mix-down appears here), though, the Fish poured their chaotic all into Electric Music, (arguably) outgunning the celebrated psychedelic frontiers represented by the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

Musically, the Fish revolved around Melton’s blistering, raga-like guitar runs – which sparred with McDonald’s vocals – and Cohen’s buzzsaw Farfisa leads, which took Al Kooper’s keyboard work with Bob Dylan to an electrifying extreme. Their ostentatious approach is so varied, though, that high-minded analysis is useless. Blues structures collide with unconventional time changes, classical composition blends with backwoods harmonica, straightforward folk/rock morphs into baroque improv, jazz/world music undertones float by – Electric Music came at listeners from myriad angles.

Lyrically, the Fish were provocative, outrageous, absurd. Politically strident, yes, but their protests, like the scathing “Superbird” – Melton’s wildfire guitar front-and-centre – carried plenty of good-natured, common sense humour. Their aural acid trips, a Fish specialty in the early years, are infused with grandeur and exploratory wonder. But they could be darkly fatalistic, too, as on the feral “Death Sound Blues”. From the hyper-blues riffs opening the tumbling rollercoaster “Flying High”, Electric Music transcends the polite coffeehouse fare often passing for 1960s folk/rock. McDonald’s wry, wide-eyed vocal approach is perfectly apropos here, and even better on “Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine”. A character sketch of sorts, a romance gone awry, it leaves boy/girl, moon/spoon pop fare in the dust, its unconventional rhythms and surreal storytelling making it the album’s most compelling track.

There were less-distinguished moments: “Sad And Lonely Times”, pleasant as it is, aims for a Byrds-style melding of psych and country, and misses the mark; “Love”, more-or-less straight boogie, gets by on some intricate interplay. But it’s an inadvertent preview of the moribund soul/blues workouts that would eventually sour the San Francisco scene.

But “The Masked Marauder” and “Grace” close out Electric Music amid some of the more outré recesses of early psych. The former, another of the group’s dizzying patchworks, traverses a cycle of spacey keyboards, childlike chants and bluesy harmonica – a band showpiece. On the latter, written for Grace Slick, they opt, for once, for some studio trickery – bells, chimes, water sound effects, reverbed vocals – an enchanting work of no small mystery.

EXTRAS: Original mono mix – not heard since the late ’60s – extensive photos, reproduced posters, liner notes by Alec Paleo, and reminiscences from many principals, including Country Joe McDonald and Barry Melton.

Like Torn

Q+A

Country Joe McDonald

What were some of the influences in this record?

R’n’B from my teenage years and C&W; cool West Coast jazz… some semi-classical stuff. I was a big fan of John Fahey and he probably influenced “Section 43”. All the songs were written by me on my guitar with harmonica.

“Not So Sweet Martha Lorraine” has a very unusual sound. How did that one come about?

It just popped into my head one day. It is odd because it has a verse, chorus and bridge. It is of course blues-based, but not a blues as such. The guitar parts and organ give it a unique sound. Also Chicken and Bruce gave everything a very distinct drum and bass bottom to the songs – not typical of rock or blues bands.

How did “Superbird” go over back then? Was it censored from radio?

I don’t remember anyone ever objecting to “Superbird”. Of course there was hardly any radio for us to get play on back then. Just progressive FM stations and very few of those. I think we put it in our shows all the time because it had a nice beat and seemed like a regular R’n’B song.

INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN