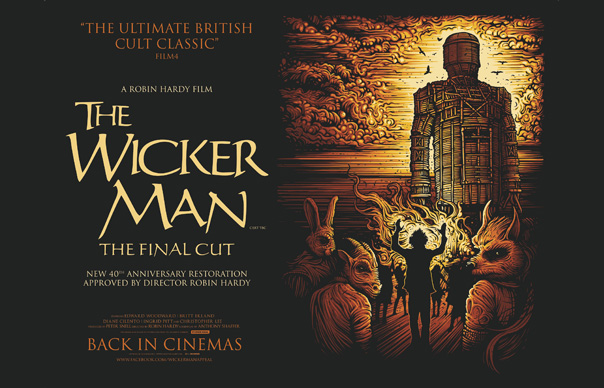

The Wicker Man, the granddaddy of British cult horror movies celebrates its 40th anniversary with what we’re told is ‘The Final Cut’ making an appearance in cinemas this month before a Blu-ray and DVD release. Coincidentally, the BFI are releasing on DVD a near-forgotten BBC Play For Today,...

The Wicker Man, the granddaddy of British cult horror movies celebrates its 40th anniversary with what we’re told is ‘The Final Cut’ making an appearance in cinemas this month before a Blu-ray and DVD release.

Coincidentally, the BFI are releasing on DVD a near-forgotten BBC Play For Today, Robin Redbreast, that shares similar themes with The Wicker Man. Although today the farming methods practised in most rural communities are sophisticated and modern, a cold, miserable spring can still prove disastrous for a crop. Such a failure might prompt a correspondence with DEFRA, or perhaps a concerned editorial on Farming Today; in these two films, however, a successful harvest is secured by other means.

Robin Redbreast – which originally aired in December 1970 as part of the BBC’s Play For Today strand – and 1974’s The Wicker Man are part of a wider cultural re-engagement with England’s folkloric history during the late Sixties and early Seventies. Led Zeppelin got it together at Bron-Yr-Aur, folk musicians embraced the spirit of old Albion, and authors Alan Garner and Susan Cooper delved into Arthurian magic, Gaia myths and the occult history of Britain. In cinemas, Blood On Satan’s Claw, Winstanley and Witchfinder General revisited an older, agrarian landscape. But Robin Redbreast and The Wicker Man – along with another BBC Play For Today, Penda’s Fen – had slightly different heads on. They were not so much concerned with reviving the past as they were with illustrating the continued existence of pagan traditions in contemporary life. They also both drew inspiration from the same real life incident: the 1945 murder of farmer Charles Walton in Lower Quinton, Warwickshire, who was discovered in a field with a cross carved on his face and neck and his body pinned to the ground by his pitchfork.

Both pieces follow broadly the same narrative: an outsider enters a remote community; a specific set of events must be played out to ensure a successful harvest ensues for the locals. In Robin Redbreast, the outsider is Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) a TV script editor who moves to the country to get her head together following a relationship break-up. “You don’t speak the Old Tongue, I suppose?” asks local historian Fisher (Bernard Hepton). “If you mean Anglo Saxon, not since Oxford,” replies Norah. At first, Norah finds the aarr-thee isms of the locals eccentric but harmless; less so later. Norah is presented as a modern, liberated woman, self-aware and articulate (at one point, she chides herself: “Stop talking to yourself, you’re making me nervous.”). Her counterpart in The Wicker Man, sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) is very much the opposite – an uptight man of strong Christian values, purse-lipped throughout. But whatever their differences, both Norah and Howie make the same mistake of failing to fully comprehend what’s going on around them until it’s too late. At the heart of the respective communities in Robin Redbreast The Wicker Man are Fisher and Lord Summerisle. Both are very different men: Fisher is a peculiar, owlish man – he works for the council by day – with none of the apparent charisma of the more urbane, intellectual Lord Summerisle.

Robin Redbreast has been largely unseen since 1971. Watched today, it stands up well, accents of tharr locals notwithstanding. Director James McTaggart – a former producer of The Wednesday Play who helped launch the careers of Dennis Potter and Ken Loach – shoots Robin Redbreast straight, with the minimum of fuss and no histrionics. The Wicker Man is still very creaky, though Anthony Shaffer’s discursive script is full of compelling ideas – the clash of oppositional belief systems, the pursuit of an alternative lifestyle, the enduring power of myth – complimented by plenty of memorable images: a breast-feeding woman holding an egg in the ruined churchyard, a beetle attached by a piece of string to a pin in a school desk, the wicker man itself. The first 20 minutes or so are Hauntology 1.0: ambient noise, hymns, folk songs. But The Wicker Man doesn’t entirely live up to its reputation. The tone is inconsistent, with half the cast playing their parts as grotesques (especially Lindsay Kemp’s pub landlord) and the other half playing it straight – or trying to. As actors, Ingrid Pitt and Britt Ekland are slow to reveal their talents. Meanwhile, cast as Lord Summerisle, Christopher Lee plays Christopher Lee: ripe. The final sequence still feels genuinely transgressive, but there’s a lot of woody undergrowth to hack through before you get there.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.