Four-CD box set honours the great Krautrock producer and collaborator... When Conny Plank is credited as the man that produced the lion’s share of great experimental German music between the years of 1969 and 1980, it may yet be selling him short. Plank, like but a few production greats – Joe Meek, George Martin, Phil Spector, Martin Hannett – wasn’t just a talented studio hand: he was a collaborator, and sometimes, an architect. Krautrock as we know it would likely not exist without him. A bear of a man from Hütschenhausen, West Germany, Plank began his career as soundman for an icon of the old Germany, fading Weimar starlet Marlene Dietrich. His enthusiasm for early electronic music drew him to Cologne’s new music community, where he worked as assistant to Stockhausen. But Plank soon tired of the classical avant-garde, which he deemed stuffy and lifeless. It was in the burgeoning West German musical counterculture that he would find those closer to his artistic temperament - emergent groups such as Kraftwerk, Neu!, and Cluster. Enamoured by the possibilities of sampling and multi-track recording, it was Plank’s technical know-how that helped bring many of Krautrock’s most revolutionary records into existence. He didn’t make groups sound ‘the Conny Plank way’, or strive to capture their live sound. Instead, he explained his role as “a medium”, and helped bands to find ways to bring their ideas to life through a fusion of technology and frenzied experimentation. In an interview published in 1987, the year of his death from cancer, he summed up his philosophy with admirable brevity: “Craziness is holy.” Such legacies can be difficult to summarise, although Who’s That Man - a four-CD box honouring Plank’s career - makes a noble attempt. There are inevitable, but still painful omissions. Plank worked with Ralph Hütter and Florian Schneider for five years, starting with the 1969 album Tone Float by the proto-Kraftwerk group Organisation, and finishing with their first masterpiece, 1974’s Autobahn. None of that, of course, appears here. Instead, the first two CDs are, while something of a curate’s egg, at least faithful to the breadth of Plank’s vision: a mix of canonical Krautrock cuts, collaborations, oddities and rarities seemingly chosen because they bear clear traces of the mad scientist’s fingerprints. The two Neu! tracks here speed out to the duo’s polar reaches. “Negativland” builds from the hammer of pneumatic drills, Klaus Dinger’s motorik drums circling Michael Rother’s cosmic guitar in a fearful orbit. “Leb’ Wohl”, meanwhile, strikes a note of new-age meditation, Dinger bidding a tearful auf wiedersehen over the gentle crash of waves. A number of collaborations with Cluster’s Dieter Moebius showcases the pair’s playful studiocraft – from the proto-techno of 1982’s “Pitch Control”, recorded with Guru Guru drummer Mani Neumeier, to “Farmer Gabriel”, a bizarre tale of chicken slaughter narrated by the Red Krayola’s Mayo Thompson. One fan of Cluster’s early work was Brian Eno, who travelled to Plank’s studio in June 1977 to record with Moebius and Rodelius - and, one suspects, to pick up a few tricks in the process. Included here is “Broken Head”, a surrealistic highlight from 1978’s collaborative After The Heat. Less interesting are the proggier selections: the interminable 14 minutes of Ibliss’ jazzy, saxophone-heavy “Drops”, and Streetmark’s misfiring cover of “Eleanor Rigby”. But Eurythmics’ “Le Sinistre”, originally a B-side to the group’s 1981 single “Never Gonna Cry Again”, cloaks Annie Lennox’s voice in the sonic tropes of horror cinema, while two tracks by electro-industrial duo D.A.F suggest that for all Plank’s association with Krautrock, he continued to innovate well into the post-punk ‘80s. The third disc passes Plank productions over to a team of remixers, who with the honourable exception of Boredoms’ Yamataka Eye – who turns in a psychedelic mangling of Neu!’s “Fur Immer” – add little but height to the European Remix Mountain. The final disc unearths a performance by the trio of Plank, Moebius and Arno Steffen, recorded in Mexico, 1986. A strange soup of Arp and Oberheim synthesisers, blasts of trumpet, primitive techno and occasional enthusiastic yodelling, it is 80 minutes of pure invention, at times sublime and at times ridiculous. But, then, as Conny Plank might have put it, craziness is next to Godliness. Louis Pattison Q&A Dieter Moebius, Cluster How was it to work with Conny? With us, he was a collaborator – a co-musician, in a way. When he got his own studio, he bought all kinds of new things that we couldn’t afford – we could use his synthesisers, all the new gadgets. The studio was a big stall in a farmhouse - a stable, where pigs were kept. But he changed it totally. It didn’t smell anymore! We would make tape loops, stretching tape all around the room, 20 metres long, and sample things from the radio. But he was happy to remain in the background? He was very modest. But he was also very sure of what he wanted to do. He recorded a lot of things that were not his kind of music, because he liked the people. But he could have produced U2 when they started out, and he didn’t. I don’t know why – perhaps he didn’t like the guy… A show from Mexico in 1986 is included in the box. How did that tour come about? We were invited by the Goethe institute, a German cultural organisation, who paid for it all. The word travelled fast, and the shows got bigger and bigger as we went. We played in some countries where rock’n’roll was not allowed – in Chile, for example, where Pinochet was terrorising his people. For some, it was like finally – we can go to a rock show. It was Conny’s last and only tour – for him, this was unique. INTERVIEW: LOUIS PATTISON

Four-CD box set honours the great Krautrock producer and collaborator…

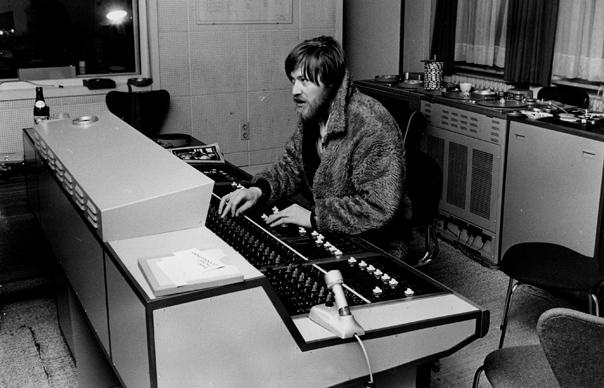

When Conny Plank is credited as the man that produced the lion’s share of great experimental German music between the years of 1969 and 1980, it may yet be selling him short. Plank, like but a few production greats – Joe Meek, George Martin, Phil Spector, Martin Hannett – wasn’t just a talented studio hand: he was a collaborator, and sometimes, an architect. Krautrock as we know it would likely not exist without him.

A bear of a man from Hütschenhausen, West Germany, Plank began his career as soundman for an icon of the old Germany, fading Weimar starlet Marlene Dietrich. His enthusiasm for early electronic music drew him to Cologne’s new music community, where he worked as assistant to Stockhausen. But Plank soon tired of the classical avant-garde, which he deemed stuffy and lifeless. It was in the burgeoning West German musical counterculture that he would find those closer to his artistic temperament – emergent groups such as Kraftwerk, Neu!, and Cluster. Enamoured by the possibilities of sampling and multi-track recording, it was Plank’s technical know-how that helped bring many of Krautrock’s most revolutionary records into existence. He didn’t make groups sound ‘the Conny Plank way’, or strive to capture their live sound. Instead, he explained his role as “a medium”, and helped bands to find ways to bring their ideas to life through a fusion of technology and frenzied experimentation. In an interview published in 1987, the year of his death from cancer, he summed up his philosophy with admirable brevity: “Craziness is holy.”

Such legacies can be difficult to summarise, although Who’s That Man – a four-CD box honouring Plank’s career – makes a noble attempt. There are inevitable, but still painful omissions. Plank worked with Ralph Hütter and Florian Schneider for five years, starting with the 1969 album Tone Float by the proto-Kraftwerk group Organisation, and finishing with their first masterpiece, 1974’s Autobahn. None of that, of course, appears here. Instead, the first two CDs are, while something of a curate’s egg, at least faithful to the breadth of Plank’s vision: a mix of canonical Krautrock cuts, collaborations, oddities and rarities seemingly chosen because they bear clear traces of the mad scientist’s fingerprints.

The two Neu! tracks here speed out to the duo’s polar reaches. “Negativland” builds from the hammer of pneumatic drills, Klaus Dinger’s motorik drums circling Michael Rother’s cosmic guitar in a fearful orbit. “Leb’ Wohl”, meanwhile, strikes a note of new-age meditation, Dinger bidding a tearful auf wiedersehen over the gentle crash of waves. A number of collaborations with Cluster’s Dieter Moebius showcases the pair’s playful studiocraft – from the proto-techno of 1982’s “Pitch Control”, recorded with Guru Guru drummer Mani Neumeier, to “Farmer Gabriel”, a bizarre tale of chicken slaughter narrated by the Red Krayola’s Mayo Thompson. One fan of Cluster’s early work was Brian Eno, who travelled to Plank’s studio in June 1977 to record with Moebius and Rodelius – and, one suspects, to pick up a few tricks in the process. Included here is “Broken Head”, a surrealistic highlight from 1978’s collaborative After The Heat.

Less interesting are the proggier selections: the interminable 14 minutes of Ibliss’ jazzy, saxophone-heavy “Drops”, and Streetmark’s misfiring cover of “Eleanor Rigby”. But Eurythmics’ “Le Sinistre”, originally a B-side to the group’s 1981 single “Never Gonna Cry Again”, cloaks Annie Lennox’s voice in the sonic tropes of horror cinema, while two tracks by electro-industrial duo D.A.F suggest that for all Plank’s association with Krautrock, he continued to innovate well into the post-punk ‘80s.

The third disc passes Plank productions over to a team of remixers, who with the honourable exception of Boredoms’ Yamataka Eye – who turns in a psychedelic mangling of Neu!’s “Fur Immer” – add little but height to the European Remix Mountain. The final disc unearths a performance by the trio of Plank, Moebius and Arno Steffen, recorded in Mexico, 1986. A strange soup of Arp and Oberheim synthesisers, blasts of trumpet, primitive techno and occasional enthusiastic yodelling, it is 80 minutes of pure invention, at times sublime and at times ridiculous. But, then, as Conny Plank might have put it, craziness is next to Godliness.

Louis Pattison

Q&A

Dieter Moebius, Cluster

How was it to work with Conny?

With us, he was a collaborator – a co-musician, in a way. When he got his own studio, he bought all kinds of new things that we couldn’t afford – we could use his synthesisers, all the new gadgets. The studio was a big stall in a farmhouse – a stable, where pigs were kept. But he changed it totally. It didn’t smell anymore! We would make tape loops, stretching tape all around the room, 20 metres long, and sample things from the radio.

But he was happy to remain in the background?

He was very modest. But he was also very sure of what he wanted to do. He recorded a lot of things that were not his kind of music, because he liked the people. But he could have produced U2 when they started out, and he didn’t. I don’t know why – perhaps he didn’t like the guy…

A show from Mexico in 1986 is included in the box. How did that tour come about?

We were invited by the Goethe institute, a German cultural organisation, who paid for it all. The word travelled fast, and the shows got bigger and bigger as we went. We played in some countries where rock’n’roll was not allowed – in Chile, for example, where Pinochet was terrorising his people. For some, it was like finally – we can go to a rock show. It was Conny’s last and only tour – for him, this was unique.

INTERVIEW: LOUIS PATTISON