It’s impossible to overestimate Chuck Berry’s mammoth influence on rock’n’roll, indeed on western culture at large. Irrespective of the bizarre way his 60-year career has played out, his music, poetry and early spirit cast an enormous shadow on everything rock’n’roll was, is, even what i...

It’s impossible to overestimate Chuck Berry’s mammoth influence on rock’n’roll, indeed on western culture at large. Irrespective of the bizarre way his 60-year career has played out, his music, poetry and early spirit cast an enormous shadow on everything rock’n’roll was, is, even what it might still be. Berry had it all. A fine singer, arranger and melodist, well-versed in pop, jazz, country, boogie and blues, he was adept at assimilating everything, formulating it anew for young ears.

His sly wordplay – compact but complex narratives and deft character sketches – reflected the hopes and aspirations, trials and tribulations of school-age (and beyond) persons. Berry was the portent of a new kind of adulthood, and those rolling, roiling and over-boiling guitar arpeggios, carried the listener into ecstatic new realms, signaling more than just a watershed. After “Roll Over Beethoven” Sinatra was on the ropes, Mitch Miller in the ditch. The music, especially once the formative Rolling Stones, Beatles and Beach Boys paid their debts, swiftly became canonical, overshadowing mightily the oft-troubled figure that created it.

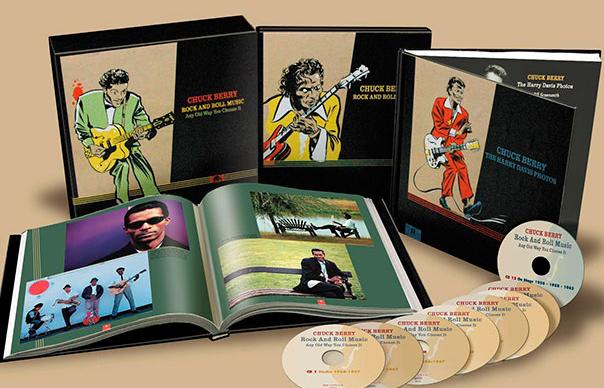

At the same time in a bitter twist of irony, Berry himself – brilliant yet paranoid, outrageously vilified in Jim Crow America – struggled to command his chaotic, if quasar-like career. Despite some notable exceptions, dime-store nostalgia, artistic redundancy and cavalier performances would dominate his career post-1965. While Berry’s been endlessly anthologised, Bear’s 16-disc, 21-hour monster represents the first effort at beginning-to-(presumably)-end documentation, foisting the brilliant early rocker against the bland pop vocalist, raucous, brain-rattling riffage against excruciating Latin balladry and “exotic” pop excursions, and finally to the diminishing return of countless remakes, remodels and, well, “My Ding-A-Ling”. Its formula invites liberal use of the skip button, yet countless rare treasures await: instrumentals galore, with extraordinary Berry/Johnnie Johnson guitar-piano interplay; superb, little-noticed Berry compositions both early (“Dear Dad”) and late (“Tulane”); the virtually forgotten Rock It, his final studio LP from 1979. His momentous, oh-so-brief 1964 post-prison comeback – “Nadine”, “Promised Land” and, eventually, his finest LP, St Louis To Liverpool – may stand as his definitive work.

As tangible as this set is – the life’s work of a musical giant – it’s the intangibles, the pure joy of Berry’s finest work, that rule the day. There was a sense of freedom flying out of those guitar solos; of possibility, optimism, adventure. Human aspirations transcending time and generations lie within those rhythms. It’s simply some of the most glorious pop music ever produced.

Luke Torn