Revitalised by Grinderman, Cave and band return with an aquatic, slow-moving work of hushed beauty... Over the last decade or so, Nick Cave has been juggling quite a few balls, work-wise, and somehow managing not to drop them. Having long ago augmented his core business as singer-songwriter with a creditable sideline as author, he's lately become rather more involved with film, creating soundtracks with Warren Ellis for movies such as The Road and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and charting various villainies in brutal style in his scripts for the John Hillcoat films The Proposition and Lawless. He's not, however, so much a Renaissance Man as a protean talent: rather than finding limitless new ways to interpret the world, Cave's able to realise a fairly narrow range of themes in diverse ways, recontextualising his fascinations - notably with the visceral trinity of religion, sex and violence - to fit different media. Cave's restlessness has affected his music, too, leading him to bifurcate his musical endeavours between The Bad Seeds and the more lubricious, erotically tortured Grinderman, two bands heading in quite different directions despite sharing effectively the same personnel. That disparity becomes even more pronounced with Push The Sky Away, a record whose thoughtful tone and drifting, becalmed manner have very little to do with rock'n'roll and much more to do with the sonic colouration explored by Cave and Ellis in their soundtracks. Ellis is clearly the musical driving force here, particularly now that Mick Harvey has departed the band. His string and keyboard loops hang over the songs like mist, haunting the action with a deep, contemplative melancholy; and freed from the imperative of carrying guitar riffs, the drums and percussion of Thomas Wydler and Jim Sclavunos are able to explore more intimate, subtle rhythms, allowing the songs to find their own pulses, rather than urging them to more explosive efforts. The effect is transformative: for all the comparative lack of overt activity, there is a much greater expressivity about the songs on Push The Sky Away, even when nothing seems to be happening. It's as if the new approach were better able to reveal the emotional currents working beneath the songs' surfaces, rather than be preoccupied with the surface activity. This works wonders with Cave's songs, as by his own admission he's more of a voyeuristic, narrative songwriter than an emotional miner: here, the music fills in the unwritten emotional content lurking behind his observations. The tone is set by the opening "We No Who U R", on which simple organ, bass and drum figures create a sombre, acquiescent mood akin to Leonard Cohen's I'm Your Man, with detail provided by a fragile flute and occasional understated keening noise. Cave's delivery likewise has something of Cohen's undemonstrative, worldly sagacity, turning the titular threat into a Zen acceptance of one's essential nature. "Wide Lovely Eyes" then heralds a sequence of songs with a watery theme, the most striking of which is "Water's Edge". Over restless, throbbing bass, hints of piano chords and string loops shift in and out, swelling and subsiding like waves lapping the shoreline, as Cave sits in his study, observing from his window the courtship rituals and youthful erotic play of boys and girls on the beach, "their legs wide to the world like bibles open", occasionally interrupting his reverie with the repeated portent, "But you grow old, and you grow cold". This sense of tainted, enervated eros continues into "Jubilee Street", a portrait of a red-light district from the aspect of a punter ambivalently caught between shame and elation, at one point "pushing my wheel of love up Jubilee Street" with "a ten ton catastrophe on a sixty pound chain", yet by the end of the song decked out in tie and tails, with "a foetus on a leash", an image that pivots uneasily between parenthood and something much more queasily disturbing. It's the first track to feature guitar, just a simple cycling figure, but it's Ellis's wistful, weeping violin that's the dominant element here, particularly during the epiphanic transformation as the song reaches its climax. In "Mermaids", the young seaside frolickers have become mermaids, sunning themselves out on rocks over a gentle lilt of vibes and guitar, with a keening violin phrase yearning at the edge of the song. Cave is prompted to muse upon myth and belief - if one believes in God, why not in mermaids too, or in 72 virgins on a chain? The nature of belief is the motor behind "We Real Cool" too, as over an ominous bass throb, piano and sad strings, his ruminations shift from facts knowable through their intimacy - family things - to the untestable prognostications of astrophysics: "Sirius is 8.6 light years away, Arcturus is 37/The past is the past, and it's here to stay", before ending on another spike of ambivalence with the observation, "Wikipedia is heaven, when you don't want to remember no more". The religio-scientific ruminations reach their apogee in the album's longest track "Higgs Boson Blues", where over quietly strummed guitar and rolling tom-toms, Cave's focus shifts between locations and characters - himself in Switzerland, Martin Luther King shot in Memphis, Miley Cyrus floating in a pool in California - as he surveys what he's subsequently described to me as "great spiritual catastrophes". The writer himself also appears, Martin Amis-like, in "Finishing Jubilee Street", an account of a dream he had shortly after writing the song in question. Again, it's the hazy, unstable nature of belief and information that drives the song, Cave's waking anxieties triggered by his dream-time marriage to a child bride. There's something deeply satisfying about the way the songs fit together as an album, their sequence strengthened both by the homogenous tone of the music, with its air of wistful melancholy, and by the way each song seems to push the next one forward, in an unimposing but implacable wave-like succession, to the closing title-track, with its soft but stolid assertion of self-belief in the face of uncertainty. It may not be the most heroic of acts, but sometimes endurance is as good as it gets. Andy Gill For an interview with Nick Cave about the new Bad Seeds album, pick up this month's Uncut - on sale now!

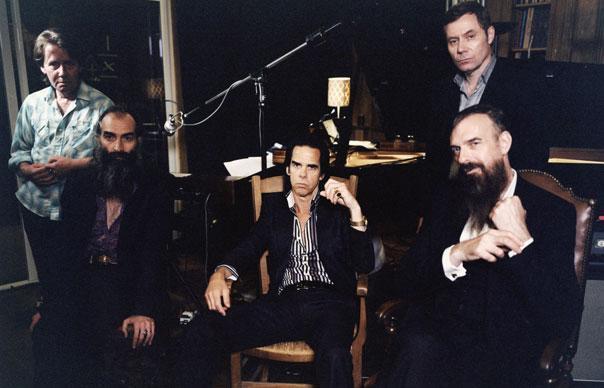

Revitalised by Grinderman, Cave and band return with an aquatic, slow-moving work of hushed beauty…

Over the last decade or so, Nick Cave has been juggling quite a few balls, work-wise, and somehow managing not to drop them. Having long ago augmented his core business as singer-songwriter with a creditable sideline as author, he’s lately become rather more involved with film, creating soundtracks with Warren Ellis for movies such as The Road and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and charting various villainies in brutal style in his scripts for the John Hillcoat films The Proposition and Lawless.

He’s not, however, so much a Renaissance Man as a protean talent: rather than finding limitless new ways to interpret the world, Cave’s able to realise a fairly narrow range of themes in diverse ways, recontextualising his fascinations – notably with the visceral trinity of religion, sex and violence – to fit different media. Cave’s restlessness has affected his music, too, leading him to bifurcate his musical endeavours between The Bad Seeds and the more lubricious, erotically tortured Grinderman, two bands heading in quite different directions despite sharing effectively the same personnel.

That disparity becomes even more pronounced with Push The Sky Away, a record whose thoughtful tone and drifting, becalmed manner have very little to do with rock’n’roll and much more to do with the sonic colouration explored by Cave and Ellis in their soundtracks. Ellis is clearly the musical driving force here, particularly now that Mick Harvey has departed the band. His string and keyboard loops hang over the songs like mist, haunting the action with a deep, contemplative melancholy; and freed from the imperative of carrying guitar riffs, the drums and percussion of Thomas Wydler and Jim Sclavunos are able to explore more intimate, subtle rhythms, allowing the songs to find their own pulses, rather than urging them to more explosive efforts.

The effect is transformative: for all the comparative lack of overt activity, there is a much greater expressivity about the songs on Push The Sky Away, even when nothing seems to be happening. It’s as if the new approach were better able to reveal the emotional currents working beneath the songs’ surfaces, rather than be preoccupied with the surface activity. This works wonders with Cave’s songs, as by his own admission he’s more of a voyeuristic, narrative songwriter than an emotional miner: here, the music fills in the unwritten emotional content lurking behind his observations.

The tone is set by the opening “We No Who U R”, on which simple organ, bass and drum figures create a sombre, acquiescent mood akin to Leonard Cohen‘s I’m Your Man, with detail provided by a fragile flute and occasional understated keening noise. Cave’s delivery likewise has something of Cohen’s undemonstrative, worldly sagacity, turning the titular threat into a Zen acceptance of one’s essential nature.

“Wide Lovely Eyes” then heralds a sequence of songs with a watery theme, the most striking of which is “Water’s Edge”. Over restless, throbbing bass, hints of piano chords and string loops shift in and out, swelling and subsiding like waves lapping the shoreline, as Cave sits in his study, observing from his window the courtship rituals and youthful erotic play of boys and girls on the beach, “their legs wide to the world like bibles open”, occasionally interrupting his reverie with the repeated portent, “But you grow old, and you grow cold”.

This sense of tainted, enervated eros continues into “Jubilee Street“, a portrait of a red-light district from the aspect of a punter ambivalently caught between shame and elation, at one point “pushing my wheel of love up Jubilee Street” with “a ten ton catastrophe on a sixty pound chain”, yet by the end of the song decked out in tie and tails, with “a foetus on a leash”, an image that pivots uneasily between parenthood and something much more queasily disturbing. It’s the first track to feature guitar, just a simple cycling figure, but it’s Ellis’s wistful, weeping violin that’s the dominant element here, particularly during the epiphanic transformation as the song reaches its climax.

In “Mermaids“, the young seaside frolickers have become mermaids, sunning themselves out on rocks over a gentle lilt of vibes and guitar, with a keening violin phrase yearning at the edge of the song. Cave is prompted to muse upon myth and belief – if one believes in God, why not in mermaids too, or in 72 virgins on a chain? The nature of belief is the motor behind “We Real Cool” too, as over an ominous bass throb, piano and sad strings, his ruminations shift from facts knowable through their intimacy – family things – to the untestable prognostications of astrophysics: “Sirius is 8.6 light years away, Arcturus is 37/The past is the past, and it’s here to stay”, before ending on another spike of ambivalence with the observation, “Wikipedia is heaven, when you don’t want to remember no more”.

The religio-scientific ruminations reach their apogee in the album’s longest track “Higgs Boson Blues“, where over quietly strummed guitar and rolling tom-toms, Cave’s focus shifts between locations and characters – himself in Switzerland, Martin Luther King shot in Memphis, Miley Cyrus floating in a pool in California – as he surveys what he’s subsequently described to me as “great spiritual catastrophes”. The writer himself also appears, Martin Amis-like, in “Finishing Jubilee Street”, an account of a dream he had shortly after writing the song in question. Again, it’s the hazy, unstable nature of belief and information that drives the song, Cave’s waking anxieties triggered by his dream-time marriage to a child bride.

There’s something deeply satisfying about the way the songs fit together as an album, their sequence strengthened both by the homogenous tone of the music, with its air of wistful melancholy, and by the way each song seems to push the next one forward, in an unimposing but implacable wave-like succession, to the closing title-track, with its soft but stolid assertion of self-belief in the face of uncertainty. It may not be the most heroic of acts, but sometimes endurance is as good as it gets.

Andy Gill

For an interview with Nick Cave about the new Bad Seeds album, pick up this month’s Uncut – on sale now!