When unpleasant right-wing governments seize control by one means or another, a lot of wishful thinking often goes on among radical artists. Hard times, they speculate, will encourage a new counterculture; angry political art will flourish in the face of oppression. We heard a lot of this rhetoric from dissenters trying to put a positive gloss on the election of David Cameron in 2010. But as yet, a provocative cultural revolt against the Tories, if there is one, remains too underground to register on most radar. In late ‘60s Brazil, however, there was ample evidence of how inspiring – and messy – the political reactions of artists could be. A military coup in 1964 had overthrown a leftist government, and protest could be found everywhere: on the streets, in art galleries, even at television song contests. While many of the country’s young singers and songwriters vehemently opposed the regime, they were not – as so frequently happens on the left – above squabbling among themselves. At the TV Globo festival in 1968, a young artist called Caetano Veloso provoked what, from the sound recordings and photographs in "Tropicalia", looks rather like a riot among the audience of left-leaning students. A year earlier, Veloso had colluded with a motley gang of other Brazilian artists to come up with a new movement that they named Tropicalia, after an installation piece by Hélio Oiticica. Their guiding principle was anthropophagy, or cannibalism: anything and everything – Brazilian folk music, American and British rock, the avant-garde, movies, philosophy, surrealism – would be enthusiastically devoured and regurgitated in a new form. For a couple of heady years, the Tropicalistas – chiefly Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes, Gal Costa, Nara Leao and Tom Zé – made a series of eclectic and mostly terrific albums showcasing a fierce local interpretation of ‘60s rock. But as Marcelo Machado’s new documentary illustrates, they had to contend with the opprobrium of both the military regime and most of the left-wing establishment. That leftist opposition was suspicious of even the most subversive American music, prizing the sanctity of Brazilian indigenous forms. When Veloso, backed by Os Mutantes, performed what was ostensibly a feedback jam at the TV Globo song contest, the hardline audience were appalled by what they perceived as a manifestation of American cultural imperialism. In "Tropicalia" you can see Mutantes turn their backs on the crowd, and hear Veloso ranting above the boos, “If you are the same in politics as you are in aesthetics, then we are done for.” Gil joined them onstage and was wounded by one of the missiles targeted at them. “We left the theatre a little frightened,” recalled Veloso in his autobiography. “On the sidewalk out front people were screaming.” “Anti-Americanism always seemed a bit shallow to me,” he notes in "Tropicalia". It’s a compelling story, and one of many that Machado chooses to tell impressionistically in his movie. "Tropicalia" begins with Gil and Veloso performing “Alfomega” together in 1969 and proclaiming, with typical contrariness, that “Tropicalia as a movement doesn’t exist anymore.” From there, Machado unleashes a kaleidoscopic bombardment of music and images, while the major players provide rueful, cerebral and (especially in the cases of Zé and the gruff, piratical theorist, Rogério Duarte) idiosyncratic commentaries. “The Tropicalia aesthetic was the only one that could take my contradictions,” claims Duarte. “Between the rogue and the man of culture… Between the European and the African.” Certain knowledge is assumed, or at least deemed unnecessary: “anthropophagy” is much discussed, but never quite explained. The richness of the subject matter inevitably means there is little room for some extraordinary tales, like that of Torquado Neto, the vampiric lyricist and “Bad Angel” who introduced marijuana to the scene before committing suicide in 1972. The psychedelic Os Mutantes could fill a film by themselves, and Machado secures interviews not only with Sergio Dias, the reformed band’s sole original member, but also with singer Rita Lee (distractedly cleaning her glasses throughout) and, frustratingly briefly, with Dias’ brother, Arnaldo Baptista, whose life and career were derailed by a taste for LSD and a leap from the window of a psychiatric hospital. The focus, understandably, rests on Gil and, especially, Veloso; “A sort of civilizing hero,” says Zé admiringly of the latter. Machado documents the pair’s 1969 arrest, imprisonment and subsequent exile in London, and uncovers home movies that show them immersed in an expat hippy scene, participating in an anarchic happening at the Isle Of Wight Festival. He’s not afraid of slowing the movie down and letting a whole song tell its own story, either, so the doleful, hirsute Veloso is caught in extreme close-up, playing “Asa Branca” on a French TV show, his words emotionally devolving into buzzes, tongue-clicks and rhythmic lip-smacks. Finally, Machado runs an extended clip of the pair returning to their home state of Bahia in 1972. It begins with crowded beaches and the ecstasies of Carnival, before Gil and his band kick into a wild version of “Back In Bahia”. For much of the film, the director has kept his protagonists hidden, only using his new interviews as voiceovers. Now, though, he reveals Veloso and Gil (Brazil's Minister Of Culture between 2003 and 2008) watching the old footage of themselves, quietly and movingly singing along, reflecting on a brief but seismic period in their lives, and in the history of Brazilian music. In 1968, Hélio Oiticica had printed the image of a protester knocked to the ground that became a flag of the Tropicalia movement, emblazoned with the slogan, “Seja marginal, seja heroi” (“Be an outcast, be a hero”). Soon enough, Gil and Veloso would become part of the country’s musical establishment, but on their own, unusually fearless terms. Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

When unpleasant right-wing governments seize control by one means or another, a lot of wishful thinking often goes on among radical artists. Hard times, they speculate, will encourage a new counterculture; angry political art will flourish in the face of oppression. We heard a lot of this rhetoric from dissenters trying to put a positive gloss on the election of David Cameron in 2010. But as yet, a provocative cultural revolt against the Tories, if there is one, remains too underground to register on most radar.

In late ‘60s Brazil, however, there was ample evidence of how inspiring – and messy – the political reactions of artists could be. A military coup in 1964 had overthrown a leftist government, and protest could be found everywhere: on the streets, in art galleries, even at television song contests. While many of the country’s young singers and songwriters vehemently opposed the regime, they were not – as so frequently happens on the left – above squabbling among themselves.

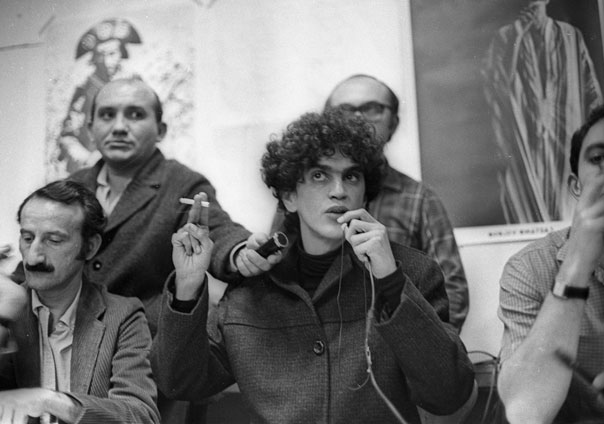

At the TV Globo festival in 1968, a young artist called Caetano Veloso provoked what, from the sound recordings and photographs in “Tropicalia”, looks rather like a riot among the audience of left-leaning students. A year earlier, Veloso had colluded with a motley gang of other Brazilian artists to come up with a new movement that they named Tropicalia, after an installation piece by Hélio Oiticica. Their guiding principle was anthropophagy, or cannibalism: anything and everything – Brazilian folk music, American and British rock, the avant-garde, movies, philosophy, surrealism – would be enthusiastically devoured and regurgitated in a new form.

For a couple of heady years, the Tropicalistas – chiefly Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Os Mutantes, Gal Costa, Nara Leao and Tom Zé – made a series of eclectic and mostly terrific albums showcasing a fierce local interpretation of ‘60s rock. But as Marcelo Machado’s new documentary illustrates, they had to contend with the opprobrium of both the military regime and most of the left-wing establishment.

That leftist opposition was suspicious of even the most subversive American music, prizing the sanctity of Brazilian indigenous forms. When Veloso, backed by Os Mutantes, performed what was ostensibly a feedback jam at the TV Globo song contest, the hardline audience were appalled by what they perceived as a manifestation of American cultural imperialism. In “Tropicalia” you can see Mutantes turn their backs on the crowd, and hear Veloso ranting above the boos, “If you are the same in politics as you are in aesthetics, then we are done for.” Gil joined them onstage and was wounded by one of the missiles targeted at them. “We left the theatre a little frightened,” recalled Veloso in his autobiography. “On the sidewalk out front people were screaming.” “Anti-Americanism always seemed a bit shallow to me,” he notes in “Tropicalia”.

It’s a compelling story, and one of many that Machado chooses to tell impressionistically in his movie. “Tropicalia” begins with Gil and Veloso performing “Alfomega” together in 1969 and proclaiming, with typical contrariness, that “Tropicalia as a movement doesn’t exist anymore.” From there, Machado unleashes a kaleidoscopic bombardment of music and images, while the major players provide rueful, cerebral and (especially in the cases of Zé and the gruff, piratical theorist, Rogério Duarte) idiosyncratic commentaries. “The Tropicalia aesthetic was the only one that could take my contradictions,” claims Duarte. “Between the rogue and the man of culture… Between the European and the African.”

Certain knowledge is assumed, or at least deemed unnecessary: “anthropophagy” is much discussed, but never quite explained. The richness of the subject matter inevitably means there is little room for some extraordinary tales, like that of Torquado Neto, the vampiric lyricist and “Bad Angel” who introduced marijuana to the scene before committing suicide in 1972. The psychedelic Os Mutantes could fill a film by themselves, and Machado secures interviews not only with Sergio Dias, the reformed band’s sole original member, but also with singer Rita Lee (distractedly cleaning her glasses throughout) and, frustratingly briefly, with Dias’ brother, Arnaldo Baptista, whose life and career were derailed by a taste for LSD and a leap from the window of a psychiatric hospital.

The focus, understandably, rests on Gil and, especially, Veloso; “A sort of civilizing hero,” says Zé admiringly of the latter. Machado documents the pair’s 1969 arrest, imprisonment and subsequent exile in London, and uncovers home movies that show them immersed in an expat hippy scene, participating in an anarchic happening at the Isle Of Wight Festival. He’s not afraid of slowing the movie down and letting a whole song tell its own story, either, so the doleful, hirsute Veloso is caught in extreme close-up, playing “Asa Branca” on a French TV show, his words emotionally devolving into buzzes, tongue-clicks and rhythmic lip-smacks.

Finally, Machado runs an extended clip of the pair returning to their home state of Bahia in 1972. It begins with crowded beaches and the ecstasies of Carnival, before Gil and his band kick into a wild version of “Back In Bahia”. For much of the film, the director has kept his protagonists hidden, only using his new interviews as voiceovers. Now, though, he reveals Veloso and Gil (Brazil’s Minister Of Culture between 2003 and 2008) watching the old footage of themselves, quietly and movingly singing along, reflecting on a brief but seismic period in their lives, and in the history of Brazilian music. In 1968, Hélio Oiticica had printed the image of a protester knocked to the ground that became a flag of the Tropicalia movement, emblazoned with the slogan, “Seja marginal, seja heroi” (“Be an outcast, be a hero”). Soon enough, Gil and Veloso would become part of the country’s musical establishment, but on their own, unusually fearless terms.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey