More death, Vicar? Aged 76, KK faces down the Reaper... When Dos Was penned the sleeve notes for Kris Kristofferson’s 1996 album A Moment Of Forever, he didn’t shrink from the superlatives. Kristofferson, he suggested, offered the emotional directness of Hank Williams, and the poetic artistry and intellect of Bob Dylan circa Blonde on Blonde. Well, no one could live up to that, and A Moment Of Forever didn’t, quite. Perhaps Was misstated his case, because Kristofferson’s gift has always been to blend the conventions of the best country music – the cask-conditioned hard stuff – with narrative. He is poetic, but he’s a storyteller. Since then Was’s role as a producer has evolved almost to the point of invisibility. For 2006’s This Old Road, the sound was stripped back, and the songs were left unvarnished, a process which continued on 2009’s Closer To The Bone, prompting comparisons with Johnny Cash’s spartan Rick Rubin recordings. Equally, the release in 2010 of Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends, a brilliant compendium of early publishing demos, showed that Kristofferson has always had this stuff in him. But intimacy has a different purpose when you’re 76 years old. “Feeling Mortal” is as good a song as Kristofferson has written; a beautifully weary country strum which contemplates death (or, if you allow the pun, drunkenness) in a way that combines a bit of self-pity with awe and thankfulness. True, it borders on self-parody; you could imagine it being delivered by Jeff Bridges’ Bad Blake in the film Crazy Heart, but Blake was almost a Kristofferson tribute act. In sentiment and execution, “Feeling Mortal” is more Hank than Dylan, yet there’s a subtle poetry in the way the lyric flits between life and death, dreams and wakefulness. Kristofferson is certainly aware of the architecture and grammar of a maudlin country song, and there’s not a syllable out of place as Was allows the suggestion of Mexican borderland to bleed into the melody. The performance is understated; the cracks in the vocal are left unrepaired. It’s funny, beautiful, and heartbreakingly sad. The mood is maintained on “Mama Stewart”, a deathbed narrative about a 94 year-old blind woman who regains her sight through “the miracle of medicine and good old time religion”. It may be about the grandmother of Kristofferson’s ex-wife, Rita Coolidge. Whatever, it’s a perilously sad composition illuminated by the faintest flicker of optimism, and a tune so slow it’s almost in reverse. More death, vicar? “Bread For The Body” comes from the perspective of a life nearing completion, but it’s a spirited anti-materialist folk song. “Life is a song for the dying to sing,” Kristofferson suggests, over ribald fiddles and twanging guitars, “it’s got to have feeling to mean anything.” “You Don’t Tell Me What To Do” is a road song about “losing myself in the soul of a song”. It sounds ready-made for Willie Nelson, but there’s a bit of Bob in the harmonica. “Stairway To The Bottom” and “Just Suppose” are classic dark night of the soul numbers, both employing the trick of a narrator describing himself in the third person. “Castaway” has Kristofferson identifying with a “lost abandoned vessel” adrift in the Caribbean, rudderless and sinking. “My Heart Was The Last One To Know” has the feeling of a 3am confessional, with Sara Watkins offering Emmylou-ish vocal support. It’s not all desperation. “The One You Chose” is an impish love song, and the closing song “Ramblin’ Jack” is a playful tribute to – we may assume – Mr Elliott, though there’s a bit of self-portraiture at work in a tale of a singer who enjoys risky nights and wasted days. “I know he ain’t afraid of where he’s goin’/and I’m sure he ain’t ashamed of where’s he’s been,” Kristofferson offers, before ending the song in a way that suggests he’s forgotten where the exit is. Just before the disc stops spinning, there’s a ghost of a chuckle. Is Kristofferson laughing at death? Probably, a bit. Alastair McKay Q&A KRIS KRISTOFFERSON The album title says a lot… Yeah! Saying it straight! The whole album is more reflective of me now, but also reflecting on different parts of my whole life. What does Don Was bring to the party? Oh, Don keeps me going! He’s great. I know he works with a lot of other people too, but I’ve been working with him for about 30 years and he has always brought the right creative inspiration for me. On this album I was recording just with him and a couple of musicians he had, and we really were on the same page all along. “My Heart Was The Last One To Know” is an old co-write with Shel Silverstein. Were many of these songs written a while ago? I’m not writing much at all these days. I write some, but I like going over a lot of songs that I haven’t necessarily performed in public that I’m getting reacquainted with and that I think are really good. That was one of them. People like Shel and Mickey Newbury were so much a part of my life. Probably the best part of my career is that I found a place where my heroes turned out to be my friends. INTERVIEW: GRAEME THOMSON

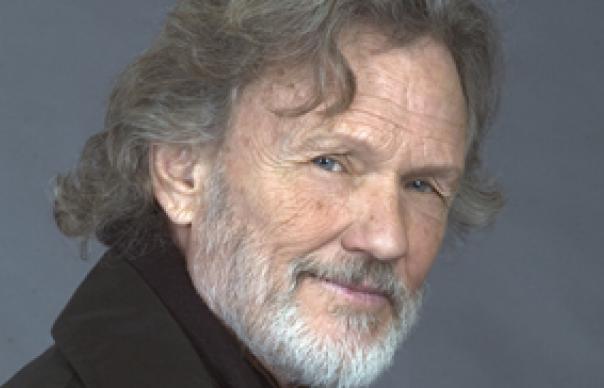

More death, Vicar? Aged 76, KK faces down the Reaper…

When Dos Was penned the sleeve notes for Kris Kristofferson’s 1996 album A Moment Of Forever, he didn’t shrink from the superlatives. Kristofferson, he suggested, offered the emotional directness of Hank Williams, and the poetic artistry and intellect of Bob Dylan circa Blonde on Blonde.

Well, no one could live up to that, and A Moment Of Forever didn’t, quite. Perhaps Was misstated his case, because Kristofferson’s gift has always been to blend the conventions of the best country music – the cask-conditioned hard stuff – with narrative. He is poetic, but he’s a storyteller.

Since then Was’s role as a producer has evolved almost to the point of invisibility. For 2006’s This Old Road, the sound was stripped back, and the songs were left unvarnished, a process which continued on 2009’s Closer To The Bone, prompting comparisons with Johnny Cash’s spartan Rick Rubin recordings. Equally, the release in 2010 of Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends, a brilliant compendium of early publishing demos, showed that Kristofferson has always had this stuff in him.

But intimacy has a different purpose when you’re 76 years old. “Feeling Mortal” is as good a song as Kristofferson has written; a beautifully weary country strum which contemplates death (or, if you allow the pun, drunkenness) in a way that combines a bit of self-pity with awe and thankfulness. True, it borders on self-parody; you could imagine it being delivered by Jeff Bridges’ Bad Blake in the film Crazy Heart, but Blake was almost a Kristofferson tribute act. In sentiment and execution, “Feeling Mortal” is more Hank than Dylan, yet there’s a subtle poetry in the way the lyric flits between life and death, dreams and wakefulness. Kristofferson is certainly aware of the architecture and grammar of a maudlin country song, and there’s not a syllable out of place as Was allows the suggestion of Mexican borderland to bleed into the melody. The performance is understated; the cracks in the vocal are left unrepaired. It’s funny, beautiful, and heartbreakingly sad.

The mood is maintained on “Mama Stewart”, a deathbed narrative about a 94 year-old blind woman who regains her sight through “the miracle of medicine and good old time religion”. It may be about the grandmother of Kristofferson’s ex-wife, Rita Coolidge. Whatever, it’s a perilously sad composition illuminated by the faintest flicker of optimism, and a tune so slow it’s almost in reverse.

More death, vicar? “Bread For The Body” comes from the perspective of a life nearing completion, but it’s a spirited anti-materialist folk song. “Life is a song for the dying to sing,” Kristofferson suggests, over ribald fiddles and twanging guitars, “it’s got to have feeling to mean anything.” “You Don’t Tell Me What To Do” is a road song about “losing myself in the soul of a song”. It sounds ready-made for Willie Nelson, but there’s a bit of Bob in the harmonica. “Stairway To The Bottom” and “Just Suppose” are classic dark night of the soul numbers, both employing the trick of a narrator describing himself in the third person. “Castaway” has Kristofferson identifying with a “lost abandoned vessel” adrift in the Caribbean, rudderless and sinking. “My Heart Was The Last One To Know” has the feeling of a 3am confessional, with Sara Watkins offering Emmylou-ish vocal support.

It’s not all desperation. “The One You Chose” is an impish love song, and the closing song “Ramblin’ Jack” is a playful tribute to – we may assume – Mr Elliott, though there’s a bit of self-portraiture at work in a tale of a singer who enjoys risky nights and wasted days. “I know he ain’t afraid of where he’s goin’/and I’m sure he ain’t ashamed of where’s he’s been,” Kristofferson offers, before ending the song in a way that suggests he’s forgotten where the exit is.

Just before the disc stops spinning, there’s a ghost of a chuckle. Is Kristofferson laughing at death? Probably, a bit.

Alastair McKay

Q&A

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON

The album title says a lot…

Yeah! Saying it straight! The whole album is more reflective of me now, but also reflecting on different parts of my whole life.

What does Don Was bring to the party?

Oh, Don keeps me going! He’s great. I know he works with a lot of other people too, but I’ve been working with him for about 30 years and he has always brought the right creative inspiration for me. On this album I was recording just with him and a couple of musicians he had, and we really were on the same page all along. “My Heart Was The Last One To Know” is an old co-write with Shel Silverstein.

Were many of these songs written a while ago?

I’m not writing much at all these days. I write some, but I like going over a lot of songs that I haven’t necessarily performed in public that I’m getting reacquainted with and that I think are really good. That was one of them. People like Shel and Mickey Newbury were so much a part of my life. Probably the best part of my career is that I found a place where my heroes turned out to be my friends.

INTERVIEW: GRAEME THOMSON