Satisfaction guaranteed! The band's fascinated early days... It’s not as if the Stones are lacking pivotal film documents – there’s the Maysles brothers’ Gimme Shelter and Godard’s One Plus One for starters, not to mention Robert Frank’s notorious, unreleased Cocksucker Blues – and they’re about to hit us with a monumental new career-overview documentary, Crossfire Hurricane. But no filmmaker ever got closer than Peter Whitehead, who was there before the rocky masks had been tugged in place and the myths coalesced. Shot over three days in 1965, on stage, backstage and on the road during a short tour of Ireland, Charlie Is My Darling, the first Stones film, is a Stones film like no other. Barely released in 1966, since trapped in legal tangles, Whitehead’s vibrant, hand-held verité documentary has emerged in various washed-out bootlegs, but the team behind this meticulous release have returned to the archives and not only restored the print but uncovered additional footage, including extended versions of the band’s fantastically raw performances: Jagger, Richards, Jones, Watts and Wyman when they were a young blues band in shirts and sports jackets, playing small venues, close enough for the hysterical audience to storm the stage. Filming shortly after the release of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, Whitehead captures them in the process of going stratospheric, loving what is happening, yet also apprehensive. Here are the Stones when they weren’t much more than kids, impersonating Elvis, getting chased by screaming fans across railway tracks, jamming Beatles songs, and, amazingly, caught in the act composing their own, as Mick talks Keith through his idea for “Sittin’ On A Fence” (“It’s about a guy sitting on a fence…”). What emerges is not a portrait of young gods. Getting so close you get to watch Keith lathering concealer over his spots, this is the band unformed, unvarnished and, when Whitehead pins them down for interviews, uncomfortable. As they get bored, show off, lark around, try on intellectual pretension and mumble, the results are astonishingly intimate, often charming, sometimes toe-curling. Just as fascinating as the picture of the band, however, is the context around them. It’s 1965, but the grey, parochial world we glimpse could as easily be 1948. Whitehead uniquely captures the real sense of the group, and their fans, trying to escape grinding reality by creating something else, something that doesn’t really exist – this music - to believe in instead. Simply essential stuff. EXTRAS: Whitehead’s original cut and Andrew Loog Oldham’s “producer’s cut” alongside the 2012 restoration and outtakes. The “Super Deluxe” edition is pricey, but amazing, including a 10-inch vinyl compilation of live 1965 performances recorded by Glyn Johns, two CDs (those same live tracks, plus the film’s soundtrack) an excellent hardback book, replica poster from the Belfast 1965 gig, and a random film cell. 10/10 Damien Love Photo credit: irish photo archive/www.irishphotoarchive.ie

Satisfaction guaranteed! The band’s fascinated early days…

It’s not as if the Stones are lacking pivotal film documents – there’s the Maysles brothers’ Gimme Shelter and Godard’s One Plus One for starters, not to mention Robert Frank’s notorious, unreleased Cocksucker Blues – and they’re about to hit us with a monumental new career-overview documentary, Crossfire Hurricane.

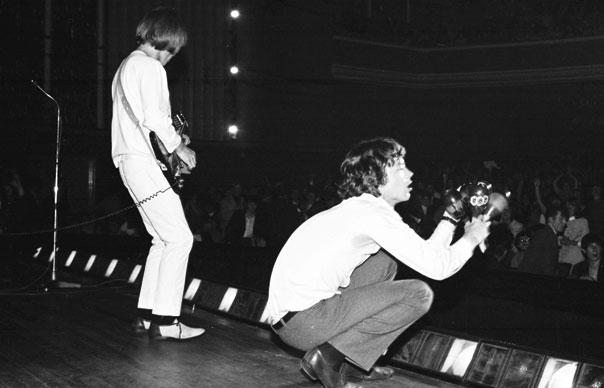

But no filmmaker ever got closer than Peter Whitehead, who was there before the rocky masks had been tugged in place and the myths coalesced. Shot over three days in 1965, on stage, backstage and on the road during a short tour of Ireland, Charlie Is My Darling, the first Stones film, is a Stones film like no other.

Barely released in 1966, since trapped in legal tangles, Whitehead’s vibrant, hand-held verité documentary has emerged in various washed-out bootlegs, but the team behind this meticulous release have returned to the archives and not only restored the print but uncovered additional footage, including extended versions of the band’s fantastically raw performances: Jagger, Richards, Jones, Watts and Wyman when they were a young blues band in shirts and sports jackets, playing small venues, close enough for the hysterical audience to storm the stage.

Filming shortly after the release of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, Whitehead captures them in the process of going stratospheric, loving what is happening, yet also apprehensive. Here are the Stones when they weren’t much more than kids, impersonating Elvis, getting chased by screaming fans across railway tracks, jamming Beatles songs, and, amazingly, caught in the act composing their own, as Mick talks Keith through his idea for “Sittin’ On A Fence” (“It’s about a guy sitting on a fence…”).

What emerges is not a portrait of young gods. Getting so close you get to watch Keith lathering concealer over his spots, this is the band unformed, unvarnished and, when Whitehead pins them down for interviews, uncomfortable. As they get bored, show off, lark around, try on intellectual pretension and mumble, the results are astonishingly intimate, often charming, sometimes toe-curling.

Just as fascinating as the picture of the band, however, is the context around them. It’s 1965, but the grey, parochial world we glimpse could as easily be 1948. Whitehead uniquely captures the real sense of the group, and their fans, trying to escape grinding reality by creating something else, something that doesn’t really exist – this music – to believe in instead. Simply essential stuff.

EXTRAS: Whitehead’s original cut and Andrew Loog Oldham’s “producer’s cut” alongside the 2012 restoration and outtakes. The “Super Deluxe” edition is pricey, but amazing, including a 10-inch vinyl compilation of live 1965 performances recorded by Glyn Johns, two CDs (those same live tracks, plus the film’s soundtrack) an excellent hardback book, replica poster from the Belfast 1965 gig, and a random film cell.

10/10

Damien Love

Photo credit: irish photo archive/www.irishphotoarchive.ie