Lou Reed was back in the news last week and for reasons other than his recent life-saving liver transplant. It turned out that some boorish actor, a self-styled hell-raiser, Rhys Ifans, by name, had thrown a bit of a strop during a newspaper interview and so one of the Saturday broadsheets, presumably stuck for anything else to fill its pages, canvassed some notable journalists about their most difficult celebrity interview. Two of the first three writers they spoke to nominated Lou, one of them describing him as ‘vile and bullying’, not to mention ‘fantastically hostile and contemptuous’. The same sensitive soul, previously a fan, was left bereft by Lou’s behaviour. “We were meant to see him play that night, but I just went back to my hotel room and wept,” he recalled, lip doubtless quavering at the memory, which probably would have made Lou laugh out loud if he’d known. Lou could definitely be touchy and a conversation with him was a little like putting your hand in a fire. But by some great good fortune I was never exposed to his full withering wrath and where others may have felt chewed up by him I seem to have escaped serial encounters relatively unscathed. I was more than once reduced to tears by things he said, but usually of laughter. Anyway, the article I’m talking about made me think about people I’ve interviewed over the years who turned out to be in one way or another ‘difficult’. I have spent perhaps more time than is reasonable with an assortment of cantankerous souls, but none worse than, you may be surprised to learn, the Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot (pictured above), in whose inhospitable company I spent an uncomfortable hour or so in October 1975. He was staying at London’s Westbury Hotel and barrels into his suite like someone looking for trouble who won’t be happy until he finds it, an unexpectedly burly man in a leather flying jacket, with a face that’s clearly seen hard times and worse weather. “Man flies all the way from Frankfurt,” he’s shouting over his shoulder as he comes through the door, “the least he expects of his record company is that they get him a goddamn beer.” Gordon throws a case across the room, follows it with a shoulder bag he flings with some force against a wall. “Someone,” he booms, “get me a drink,” and you’d have to say straight off that the first impression Gordon makes is that he’s a bit of a bully, someone used to having his own way in pretty much every circumstance, and very much in love with the sound of his own voice. As are, of course, at the time of which I’m writing, many hundreds of thousands of fans around the world, Gordon the author of mawkish MOR hits like the folkie “Early Morning Rain” and “If You Could Read My Mind”, songs that have or will be covered by Dylan, Cash and Presley, among others. Anyway, here’s Gordon storming around the room, banging doors, ill-tempered. I presume he’s looking for the mini-bar, which I have myself only located with some difficulty during a search of the premises during a long wait for Gordon, whose flight from Frankfurt has been considerably delayed. “It’s built into the cabinet over there,” I pipe up now, clearly startling the Canadian songsmith. “Who the fuck,” Gordon wants to know, noticing me for the first time, “are you?” I tell him I’m from what used to be Melody Maker, and he looks at me suspiciously, like he thinks I might suddenly leap on him and nail his head to the door frame. “And what are you doing here?” It’s a good question. Why I am here to talk to this grizzled old cur, I have even after all these years absolutely no fucking idea. I suspect, however, it has much to do with my nemesis at Melody Maker, quiche-nibbling, cravat-sporting, Chablis-sipping assistant editor Michael Watts, who with impish regularity sends me out to interview people he knows I won’t get on with, clearly in the hope that at least one of them will end up taking a swing at me. Anyway, back at the Westbury, I’m engaged in what passes for conversation with grumpy Gordon, the morose Canadian telling me now with no great animation about his early career in Canada, where he played the same small club circuit as Joni Mitchell, or Joni Anderson as Gordon knew her back then, the mists of time just parting, the way he tells it. “This is going way back,” he says, like he’s remembering the world’s first dawn. “We were just callow youths. You were probably kicking the slats out of your cradle.” These days, he only tours maybe once every 18 months, the rest of his time spent sailing on the Great Lakes, he tells me, mistakenly thinking I’m interested. “There comes a point, though,” he adds with a manly shrug, “when a man has to get out and be active. It’s my job. A man,” he says with suitably masculine sagacity, “needs his work.” How we come to be talking about it, I can’t remember, but the next thing you know, Gordon’s lambasting the young American draft dodgers who made lives for themselves in exile in Canada rather than get shipped off to Vietnam. As far as he’s concerned, Canada should have booted them all out, sent them packing back to the States or banged them up in prison. A man, he says, is nothing without a sense of duty. If he’d been an American, he would have volunteered to fight in Southeast Asia. “Only Americans know the anguish of that war, but what kind of leniency can you extend to a guy who skips out of his country when 50,000 men get killed in a war?” I may in some circumstances have let this pass. But during the long wait for Gordon, I appear to have grown somewhat cantankerous. So I launch into a patently ridiculous speech about America and Vietnam and the peace movement, generally coming on here like a veteran of the Weather Underground or the SLA, a history of random bombings on an FBI rap sheet, guns stashed in every cupboard of a South Compton safe-house, Patty Hearst trussed up in a closet close-by, peeing on the carpet and going out of her mind. “Why didn’t I write about the war?” he says, in answer to that very question. “It was none of my goddamn business,” he says. “The United States at that time was a target for every loose tongue around. I didn’t think it was my place to say anything. I have,” he goes on, “a lot of sympathy for America. I also make a lot of money there. And if you don’t mind me saying so, some of the nicest people on earth are Americans and I wish you wouldn’t dwell on this particular subject. I suggest we talk about something else.” We do. His songs. I have come across in one of them the following lyrics: “In the name of love she came, this foolish winsome girl/She was all decked out like a rainbow trout. . .” I fail to stop myself laughing out loud when I read this to Gordon from my notebook, where I have dutifully jotted it down, alongside adjectives like “sentimental” and words like “schmaltz”. “Schmaltz?” Gordon seethes through grimly gritted teeth, almost coming at me out of his chair. “You’re calling my songs sentimental?” In a word, yes. Gordon, taking deep breaths, says then: “Well, I guess I’ve been accused of that before. Just not to my face. But I’d defend myself against an accusation like that. We all know the world isn’t exactly in a placid state right now, but I don’t think we have to dwell on it.” Your songs, generally, though, are pretty wet, aren’t they? “Wet?” Like I say, they have a tendency towards sentimentality, weepiness, that sort of thing. “One or two, maybe,” he grudgingly consents. “But people love ‘em. So I sing ‘em. I’m not going to apologise if you have a problem with that.” It must be embarrassing, though, being lumped in with the kind of tepid troubadours whose serial confessional outpourings are often sentimental to the point of complete banality. “Sentimental to the point of complete banality?” Gordon splutters. “Whose work are we talking about?” I reel off a list of singer-songwriters, most of whom turn out to be friends of his and mention of whom in such a disparaging context is turning his face puce. “Interview’s over, son,” he snaps. I tell him I have one more question, and he leans over the table between us, close enough for me to feel his breath on my face. “Listen,” he says, “beat it now. That’s my advice,” Gordon sounding like he means business in a big way. I’m out the door before he unclenches his fist.

Lou Reed was back in the news last week and for reasons other than his recent life-saving liver transplant. It turned out that some boorish actor, a self-styled hell-raiser, Rhys Ifans, by name, had thrown a bit of a strop during a newspaper interview and so one of the Saturday broadsheets, presumably stuck for anything else to fill its pages, canvassed some notable journalists about their most difficult celebrity interview.

Two of the first three writers they spoke to nominated Lou, one of them describing him as ‘vile and bullying’, not to mention ‘fantastically hostile and contemptuous’. The same sensitive soul, previously a fan, was left bereft by Lou’s behaviour. “We were meant to see him play that night, but I just went back to my hotel room and wept,” he recalled, lip doubtless quavering at the memory, which probably would have made Lou laugh out loud if he’d known.

Lou could definitely be touchy and a conversation with him was a little like putting your hand in a fire. But by some great good fortune I was never exposed to his full withering wrath and where others may have felt chewed up by him I seem to have escaped serial encounters relatively unscathed. I was more than once reduced to tears by things he said, but usually of laughter.

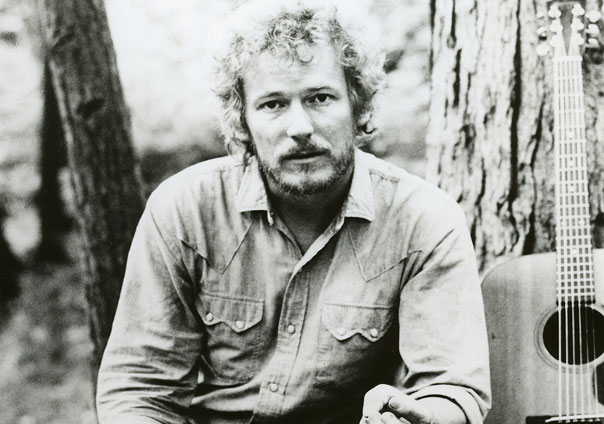

Anyway, the article I’m talking about made me think about people I’ve interviewed over the years who turned out to be in one way or another ‘difficult’. I have spent perhaps more time than is reasonable with an assortment of cantankerous souls, but none worse than, you may be surprised to learn, the Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot (pictured above), in whose inhospitable company I spent an uncomfortable hour or so in October 1975.

He was staying at London’s Westbury Hotel and barrels into his suite like someone looking for trouble who won’t be happy until he finds it, an unexpectedly burly man in a leather flying jacket, with a face that’s clearly seen hard times and worse weather.

“Man flies all the way from Frankfurt,” he’s shouting over his shoulder as he comes through the door, “the least he expects of his record company is that they get him a goddamn beer.”

Gordon throws a case across the room, follows it with a shoulder bag he flings with some force against a wall.

“Someone,” he booms, “get me a drink,” and you’d have to say straight off that the first impression Gordon makes is that he’s a bit of a bully, someone used to having his own way in pretty much every circumstance, and very much in love with the sound of his own voice.

As are, of course, at the time of which I’m writing, many hundreds of thousands of fans around the world, Gordon the author of mawkish MOR hits like the folkie “Early Morning Rain” and “If You Could Read My Mind”, songs that have or will be covered by Dylan, Cash and Presley, among others.

Anyway, here’s Gordon storming around the room, banging doors, ill-tempered. I presume he’s looking for the mini-bar, which I have myself only located with some difficulty during a search of the premises during a long wait for Gordon, whose flight from Frankfurt has been considerably delayed.

“It’s built into the cabinet over there,” I pipe up now, clearly startling the Canadian songsmith.

“Who the fuck,” Gordon wants to know, noticing me for the first time, “are you?”

I tell him I’m from what used to be Melody Maker, and he looks at me suspiciously, like he thinks I might suddenly leap on him and nail his head to the door frame.

“And what are you doing here?”

It’s a good question. Why I am here to talk to this grizzled old cur, I have even after all these years absolutely no fucking idea. I suspect, however, it has much to do with my nemesis at Melody Maker, quiche-nibbling, cravat-sporting, Chablis-sipping assistant editor Michael Watts, who with impish regularity sends me out to interview people he knows I won’t get on with, clearly in the hope that at least one of them will end up taking a swing at me.

Anyway, back at the Westbury, I’m engaged in what passes for conversation with grumpy Gordon, the morose Canadian telling me now with no great animation about his early career in Canada, where he played the same small club circuit as Joni Mitchell, or Joni Anderson as Gordon knew her back then, the mists of time just parting, the way he tells it.

“This is going way back,” he says, like he’s remembering the world’s first dawn. “We were just callow youths. You were probably kicking the slats out of your cradle.”

These days, he only tours maybe once every 18 months, the rest of his time spent sailing on the Great Lakes, he tells me, mistakenly thinking I’m interested.

“There comes a point, though,” he adds with a manly shrug, “when a man has to get out and be active. It’s my job. A man,” he says with suitably masculine sagacity, “needs his work.”

How we come to be talking about it, I can’t remember, but the next thing you know, Gordon’s lambasting the young American draft dodgers who made lives for themselves in exile in Canada rather than get shipped off to Vietnam. As far as he’s concerned, Canada should have booted them all out, sent them packing back to the States or banged them up in prison.

A man, he says, is nothing without a sense of duty. If he’d been an American, he would have volunteered to fight in Southeast Asia.

“Only Americans know the anguish of that war, but what kind of leniency can you extend to a guy who skips out of his country when 50,000 men get killed in a war?”

I may in some circumstances have let this pass. But during the long wait for Gordon, I appear to have grown somewhat cantankerous. So I launch into a patently ridiculous speech about America and Vietnam and the peace movement, generally coming on here like a veteran of the Weather Underground or the SLA, a history of random bombings on an FBI rap sheet, guns stashed in every cupboard of a South Compton safe-house, Patty Hearst trussed up in a closet close-by, peeing on the carpet and going out of her mind.

“Why didn’t I write about the war?” he says, in answer to that very question. “It was none of my goddamn business,” he says. “The United States at that time was a target for every loose tongue around. I didn’t think it was my place to say anything. I have,” he goes on, “a lot of sympathy for America. I also make a lot of money there. And if you don’t mind me saying so, some of the nicest people on earth are Americans and I wish you wouldn’t dwell on this particular subject. I suggest we talk about something else.”

We do. His songs. I have come across in one of them the following lyrics: “In the name of love she came, this foolish winsome girl/She was all decked out like a rainbow trout. . .” I fail to stop myself laughing out loud when I read this to Gordon from my notebook, where I have dutifully jotted it down, alongside adjectives like “sentimental” and words like “schmaltz”.

“Schmaltz?” Gordon seethes through grimly gritted teeth, almost coming at me out of his chair. “You’re calling my songs sentimental?”

In a word, yes.

Gordon, taking deep breaths, says then: “Well, I guess I’ve been accused of that before. Just not to my face. But I’d defend myself against an accusation like that. We all know the world isn’t exactly in a placid state right now, but I don’t think we have to dwell on it.”

Your songs, generally, though, are pretty wet, aren’t they?

“Wet?”

Like I say, they have a tendency towards sentimentality, weepiness, that sort of thing.

“One or two, maybe,” he grudgingly consents. “But people love ‘em. So I sing ‘em. I’m not going to apologise if you have a problem with that.”

It must be embarrassing, though, being lumped in with the kind of tepid troubadours whose serial confessional outpourings are often sentimental to the point of complete banality.

“Sentimental to the point of complete banality?” Gordon splutters. “Whose work are we talking about?”

I reel off a list of singer-songwriters, most of whom turn out to be friends of his and mention of whom in such a disparaging context is turning his face puce.

“Interview’s over, son,” he snaps.

I tell him I have one more question, and he leans over the table between us, close enough for me to feel his breath on my face.

“Listen,” he says, “beat it now. That’s my advice,” Gordon sounding like he means business in a big way.

I’m out the door before he unclenches his fist.