The vanguard's first three albums are difficult, but peerless... Van Dyke Parks is pop’s weirdest straight guy. Or, just as plausibly, he is rock’s straightest weird guy. Whether the foreground of his reputation is dominated by his oddness or his ordinariness depends on who is holding the binoculars. To Mike Love of the Beach Boys, listening to the lyrics penned for SMiLE, Parks might represent the embodiment of kooky indulgence. There is a case for that. (The prosecution will now hear a recording of Brian Wilson singing “Vega-tables”.) But listen to Parks now, with a clearer understanding of the context of his work, and its plain that his primary motivation has always been to celebrate common decency. In truth, Parks has always been misunderstood, and the incomprehension which greeted his debut in 1967 clouded his reputation. Warner Brothers signed Parks in the belief that he might bring with him the secrets of Brian Wilson’s genius. Over time, he delivered, though his success came as a producer, midwifing the careers of Randy Newman and Ry Cooder, among others. But, thanks to the Warners publicist who took a trade ad, boasting that the company had “lost $35,509 on 'the album of the year' (dammit)”, Song Cycle was seen as an expensive folly, albeit one worth revisiting (it inspired Joanna Newsom’s Ys). Parks modestly suggests that it’s a record on which he made every possible mistake. It’s true that Song Cycle does not go out of its way to accommodate the listener. It flits between styles. Its songs are abstruse affairs, masking the intentions of their author. In a way, it’s a protest record, but the iron fist of Parks’ anger is gloved in velvety sonic experiments, as he and producer Lenny Waronker explore the possibilities of 8-track recording. It offers a kaleidoscopic vision of American popular music, drifting in and out of focus, like show tunes wafting from a passing riverboat. A snippet of Steve Young playing a gospel country tune crashes into the theatrical melancholy of “Vine Street”, a Randy Newman composition in Brechtian dungarees; then you get “Palm Desert”, which has a chorus, almost, and some birdsong, while musing lyrically about “the very old search for the truth within the bounds of toxicity”. It feels, at times, like California, reimagined as a musical, but without hackneyed references to girls or surf. Instead, on “Widows Walk”, Park addresses civil strife, while the beautiful instrumental, “Colours” employs Caribbean colours, to point forward to the record that Parks considers his best, 1972’s Discover America. On paper, Discover America is a calypso record, with Parks remodelling traditional songs in a celebration of Trinidadian culture. It does that, and it sounds joyous. But it’s not all sunlight. Hidden behind the breezy rhythms, he’s also making a sly comment about post-colonial Trinidad and, by implication, race relations in the US. That sounds grim, but it’s largely playful, and sometimes straightforwardly funny (see “G-Man Hoover”, which tirelessly mocks the fabled FBI chief). Little Feat provide the salty atmospherics on “FDR in Trinidad”, and the gangster theme is continued on the lazy, tropical-sounding “John Jones”. Ry Cooder is an obvious point of reference, but, really, it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that The Clash colonised this territory a decade later in their pan-global phase (though Parks is slower to anger, and has superior table manners). The calypso experiment was continued on the 1975 release, Clang Of The Yankee Reaper, which has its moments (the exuberant “Tribute To Spree”), while sounding more frivolous, and dated in a way the first two albums do not. On Song Cycle and Discover America, Parks looked back to face the future, and made music that still sounds mysterious. It’s not timeless, exactly, but neither is it dated. Perhaps it still intrigues because it has almost nothing to do with rock. You might call it beat, without the jazz; or Americana, without the tractors. Alastair McKay Q&A Song Cycle still seems mysterious: what was it about? From June 1963, when I got my first job, arranging “The Bare Necessities” - that was to pay for the black suit and the airplane ticket to my brother’s funeral. That is before John Kennedy got his, and then Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. In fact, we were in a psychological collapse, Americans, every damn one of us! So when you listen to Song Cycle, you get that sense of catastrophe. I talk about my father’s war trunk. I say ‘God send your son home safe to you’. I use that squaresville expression for my father, who had lost his son, my brother. So it was an expensive record for me. Warner Brothers said it was expensive for them – they were lying through their teeth. Discover America has an interesting mood – both happy and sad. You can feel that there is an underlying contentment, but beyond that there is urgency. Those are the writings of Trinidadian authors and they show great authorial command. I liked the troubadour: music that is the truth, the ballad, and the news that’s fit to sing. I saw that in Phil Ochs work; it somehow captured an era. INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

The vanguard’s first three albums are difficult, but peerless…

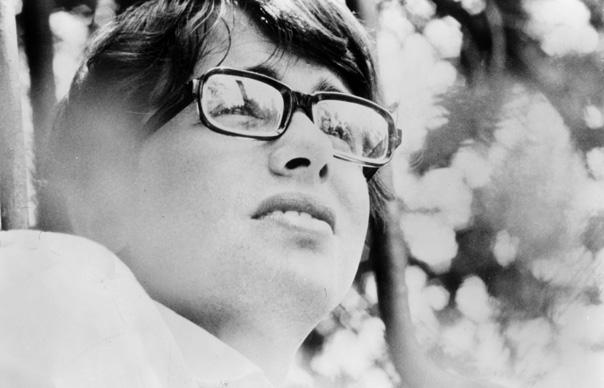

Van Dyke Parks is pop’s weirdest straight guy. Or, just as plausibly, he is rock’s straightest weird guy. Whether the foreground of his reputation is dominated by his oddness or his ordinariness depends on who is holding the binoculars. To Mike Love of the Beach Boys, listening to the lyrics penned for SMiLE, Parks might represent the embodiment of kooky indulgence. There is a case for that. (The prosecution will now hear a recording of Brian Wilson singing “Vega-tables”.) But listen to Parks now, with a clearer understanding of the context of his work, and its plain that his primary motivation has always been to celebrate common decency.

In truth, Parks has always been misunderstood, and the incomprehension which greeted his debut in 1967 clouded his reputation. Warner Brothers signed Parks in the belief that he might bring with him the secrets of Brian Wilson’s genius. Over time, he delivered, though his success came as a producer, midwifing the careers of Randy Newman and Ry Cooder, among others.

But, thanks to the Warners publicist who took a trade ad, boasting that the company had “lost $35,509 on ‘the album of the year’ (dammit)”, Song Cycle was seen as an expensive folly, albeit one worth revisiting (it inspired Joanna Newsom’s Ys). Parks modestly suggests that it’s a record on which he made every possible mistake.

It’s true that Song Cycle does not go out of its way to accommodate the listener. It flits between styles. Its songs are abstruse affairs, masking the intentions of their author. In a way, it’s a protest record, but the iron fist of Parks’ anger is gloved in velvety sonic experiments, as he and producer Lenny Waronker explore the possibilities of 8-track recording.

It offers a kaleidoscopic vision of American popular music, drifting in and out of focus, like show tunes wafting from a passing riverboat. A snippet of Steve Young playing a gospel country tune crashes into the theatrical melancholy of “Vine Street”, a Randy Newman composition in Brechtian dungarees; then you get “Palm Desert”, which has a chorus, almost, and some birdsong, while musing lyrically about “the very old search for the truth within the bounds of toxicity”. It feels, at times, like California, reimagined as a musical, but without hackneyed references to girls or surf. Instead, on “Widows Walk”, Park addresses civil strife, while the beautiful instrumental, “Colours” employs Caribbean colours, to point forward to the record that Parks considers his best, 1972’s Discover America.

On paper, Discover America is a calypso record, with Parks remodelling traditional songs in a celebration of Trinidadian culture. It does that, and it sounds joyous. But it’s not all sunlight. Hidden behind the breezy rhythms, he’s also making a sly comment about post-colonial Trinidad and, by implication, race relations in the US. That sounds grim, but it’s largely playful, and sometimes straightforwardly funny (see “G-Man Hoover”, which tirelessly mocks the fabled FBI chief). Little Feat provide the salty atmospherics on “FDR in Trinidad”, and the gangster theme is continued on the lazy, tropical-sounding “John Jones”. Ry Cooder is an obvious point of reference, but, really, it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that The Clash colonised this territory a decade later in their pan-global phase (though Parks is slower to anger, and has superior table manners).

The calypso experiment was continued on the 1975 release, Clang Of The Yankee Reaper, which has its moments (the exuberant “Tribute To Spree”), while sounding more frivolous, and dated in a way the first two albums do not. On Song Cycle and Discover America, Parks looked back to face the future, and made music that still sounds mysterious. It’s not timeless, exactly, but neither is it dated. Perhaps it still intrigues because it has almost nothing to do with rock. You might call it beat, without the jazz; or Americana, without the tractors.

Alastair McKay

Q&A

Song Cycle still seems mysterious: what was it about?

From June 1963, when I got my first job, arranging “The Bare Necessities” – that was to pay for the black suit and the airplane ticket to my brother’s funeral. That is before John Kennedy got his, and then Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King. In fact, we were in a psychological collapse, Americans, every damn one of us! So when you listen to Song Cycle, you get that sense of catastrophe. I talk about my father’s war trunk. I say ‘God send your son home safe to you’. I use that squaresville expression for my father, who had lost his son, my brother. So it was an expensive record for me. Warner Brothers said it was expensive for them – they were lying through their teeth.

Discover America has an interesting mood – both happy and sad.

You can feel that there is an underlying contentment, but beyond that there is urgency. Those are the writings of Trinidadian authors and they show great authorial command. I liked the troubadour: music that is the truth, the ballad, and the news that’s fit to sing. I saw that in Phil Ochs work; it somehow captured an era.

INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY