Moz reissues his fine solo debut... It’s hard to recall now, after a quarter-century of stardom, scandal, exile, rebirth and lingering notoriety, quite how dicey Morrissey’s prospects seemed in the livid aftermath of the Smiths’ disintegration. The form of previous frontmen gone solo, from Mick Jagger to Joe Strummer to Ian McCulloch, was not promising. Paul Weller, with the considerable advantages of the singer/songwriter, had successfully escaped the Jam, but by the late 80s even he faced being dropped by his label. In the winter of 1987 it seemed all too easy to imagine Morrissey, draped in his widow’s weeds, anticipating an endless circuit of cemetery tours with Howard Devoto and Linder. Of course he had considered the prospect. One of the best songs on Viva Hate is “Little Man, What Now?”, a scintillating consideration, by way of Dennis Norden’s Looks Familiar, of the fatally fleeting nature of fame: “Friday nights, 1969/ATV you murdered every line/.../Four seasons passed and they AXED you”. Was the demise of the Smiths to prove his own chopping block? That he eluded this fate is testament to his enduring genius for emergency escapology and a certain Irish luck. The luck being the unlikely emergence of Stephen Street, long-time Smiths engineer/producer, as a credible songwriting partner. The genius being his ability to fashion the urgency and trauma of the split into some of the finest songs of his career. “Suedehead”, the lead single from Viva Hate, released in February 1987, just two months after the final Smiths release, was a breezy, easily loveable, mock apology (“I’m so sorry”, addressed to both Marr and the Smiths audience, curdling into “I’m so sickened”), radiant with early spring jangle, propelled with the backing of EMI to his highest chart placing to date. But “Every Day Is Like Sunday”, was the real clincher, a career-defining song that proved indupitably that his muse could flourish outside the Smiths. Elevated by Street’s majestic, swarming string arrangement, the song felt like a coronation, the establishment of Morrissey into an honoured English lineage alongside the likes of John Betjeman (the cadging of “Come friendly bombs...” from “Slough”) and Tony Hancock (the existential English exasperation of “Sunday Afternoon At Home”, the suicidal seaside of The Punch and Judy Man). The album itself didn’t disappoint. Howling into furious life with “Alsation Cousin”, rising to a elegiac pitch on “Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together”, lost in moonglow reverie on “Late Night, Maudlin Street”, and concluding with the dreamy execution of “Margaret On The Guillotine”, it was enlived by the very desparation and urgency that was largely missing from Strangeways. It’s hard to overstate the contribution of Moz’s fellow Ed Banger and the Nosebleeds alumnus Vini Reilly - one of the few English guitarists in the same league as Marr. Reilly’s entranced playing almost redeems “Bengali In Platforms” (a song Morrissey might claim is an imaginative act of identification, part of the cast of tutued vicars, rent boys, failing boxers, and wheelchair users elsewhere in his corpus, but which singularly fails to escape patronising mockery) and sublimely stages the centrepiece of the album “Late Night Maudlin Street”. It’s a song about the pain of transition,the misery of eviction from the home, or band, you thought you’d made, and it’s the closest Morrissey ever got to kind of Joni Mitchell/Rickie Lee Jones intimate epic he revered. So it’s puzzling to find that on this reissue the song is abruptly shorn of its final minute. The puzzle is compounded when “The Ordinary Boys”, admittedly one of the weakest tracks on the album, is replaced with an, if anything, even weaker song, “Treat Me Like A Human Being”, a demo that’s incongruously lofi amid the general excellence of the remaster. Is he embarrassed by perceived weakness of singing and writing? Has Preston’s shameful treatment of Chantelle soured his feelings for “The Ordinary Boys”? These odd revisions follow the 2009 reissues of Southpaw Grammar and Maladjusted, where he reordered and revised tracklistings and commissioned new artwork. However you try to explain it, in the absence of a new record on the horizon, Morrissey increasingly resembles the elder Henry James or Wordsworth, driven to endless, fruitless, tinkering with their vital early work. Can even Morrissey escape this final ignominy? Stephen Troussé

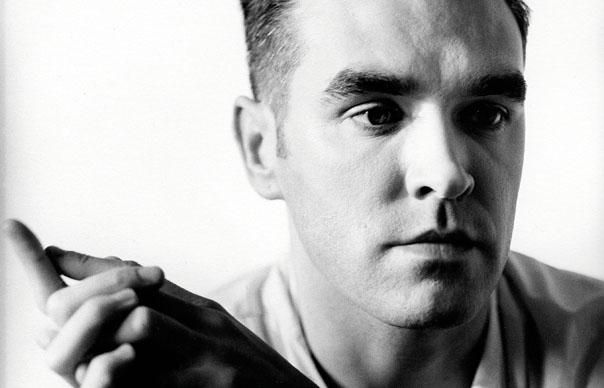

Moz reissues his fine solo debut…

It’s hard to recall now, after a quarter-century of stardom, scandal, exile, rebirth and lingering notoriety, quite how dicey Morrissey’s prospects seemed in the livid aftermath of the Smiths’ disintegration. The form of previous frontmen gone solo, from Mick Jagger to Joe Strummer to Ian McCulloch, was not promising. Paul Weller, with the considerable advantages of the singer/songwriter, had successfully escaped the Jam, but by the late 80s even he faced being dropped by his label. In the winter of 1987 it seemed all too easy to imagine Morrissey, draped in his widow’s weeds, anticipating an endless circuit of cemetery tours with Howard Devoto and Linder.

Of course he had considered the prospect. One of the best songs on Viva Hate is “Little Man, What Now?”, a scintillating consideration, by way of Dennis Norden’s Looks Familiar, of the fatally fleeting nature of fame: “Friday nights, 1969/ATV you murdered every line/…/Four seasons passed and they AXED you”. Was the demise of the Smiths to prove his own chopping block?

That he eluded this fate is testament to his enduring genius for emergency escapology and a certain Irish luck. The luck being the unlikely emergence of Stephen Street, long-time Smiths engineer/producer, as a credible songwriting partner. The genius being his ability to fashion the urgency and trauma of the split into some of the finest songs of his career.

“Suedehead”, the lead single from Viva Hate, released in February 1987, just two months after the final Smiths release, was a breezy, easily loveable, mock apology (“I’m so sorry”, addressed to both Marr and the Smiths audience, curdling into “I’m so sickened”), radiant with early spring jangle, propelled with the backing of EMI to his highest chart placing to date. But “Every Day Is Like Sunday”, was the real clincher, a career-defining song that proved indupitably that his muse could flourish outside the Smiths. Elevated by Street’s majestic, swarming string arrangement, the song felt like a coronation, the establishment of Morrissey into an honoured English lineage alongside the likes of John Betjeman (the cadging of “Come friendly bombs…” from “Slough”) and Tony Hancock (the existential English exasperation of “Sunday Afternoon At Home”, the suicidal seaside of The Punch and Judy Man).

The album itself didn’t disappoint. Howling into furious life with “Alsation Cousin”, rising to a elegiac pitch on “Angel, Angel, Down We Go Together”, lost in moonglow reverie on “Late Night, Maudlin Street”, and concluding with the dreamy execution of “Margaret On The Guillotine”, it was enlived by the very desparation and urgency that was largely missing from Strangeways.

It’s hard to overstate the contribution of Moz’s fellow Ed Banger and the Nosebleeds alumnus Vini Reilly – one of the few English guitarists in the same league as Marr. Reilly’s entranced playing almost redeems “Bengali In Platforms” (a song Morrissey might claim is an imaginative act of identification, part of the cast of tutued vicars, rent boys, failing boxers, and wheelchair users elsewhere in his corpus, but which singularly fails to escape patronising mockery) and sublimely stages the centrepiece of the album “Late Night Maudlin Street”. It’s a song about the pain of transition,the misery of eviction from the home, or band, you thought you’d made, and it’s the closest Morrissey ever got to kind of Joni Mitchell/Rickie Lee Jones intimate epic he revered.

So it’s puzzling to find that on this reissue the song is abruptly shorn of its final minute. The puzzle is compounded when “The Ordinary Boys”, admittedly one of the weakest tracks on the album, is replaced with an, if anything, even weaker song, “Treat Me Like A Human Being”, a demo that’s incongruously lofi amid the general excellence of the remaster.

Is he embarrassed by perceived weakness of singing and writing? Has Preston’s shameful treatment of Chantelle soured his feelings for “The Ordinary Boys”? These odd revisions follow the 2009 reissues of Southpaw Grammar and Maladjusted, where he reordered and revised tracklistings and commissioned new artwork. However you try to explain it, in the absence of a new record on the horizon, Morrissey increasingly resembles the elder Henry James or Wordsworth, driven to endless, fruitless, tinkering with their vital early work. Can even Morrissey escape this final ignominy?

Stephen Troussé