Neil Young is not, at a guess, an artist who suffers much from writer’s block. In the past few years, many of his albums have felt like spontaneous dispatches from an over-productive mind. He has been provoked into action by a useless president, and by an obsessive need to apply driving metapho...

Neil Young is not, at a guess, an artist who suffers much from writer’s block. In the past few years, many of his albums have felt like spontaneous dispatches from an over-productive mind.

He has been provoked into action by a useless president, and by an obsessive need to apply driving metaphors to America’s parlous economic state. Some projects have been shaped by a new relationship – with, say, producer Daniel Lanois – while others have stemmed from reunions with old collaborators, as Young cycles through the musicians he has relied upon, with an admittedly capricious brand of loyalty, for over four decades. It is easy, too, to imagine Young foraging in his own archives, repeatedly postponing the next volume of his retrospective endeavours when something old stimulates him into creating something new, at speed.

Talking to Uncut a few months ago, Young gave the impression that bashing out a book came just as simply. “Writing was a very easy thing to do,” he told Jaan Uhelszki, “things came out.” Later, though, he suggested that his artistic hyperactivity was born of necessity: “They paid me some money to write the book,” he said, “and that means I don’t have to go on the road [he has subsequently, of course, gone back on the road]. I spend money as soon as I get it. I don’t care how much money I have, I can use it to do something.”

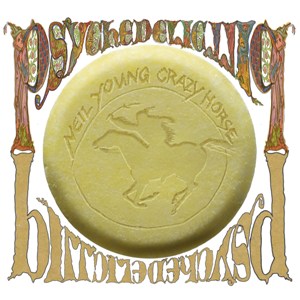

In 2012, then, this haphazard magnate has found a cunning new way to build multiple revenue streams from one idea. First, he wrote what may be an autobiography: Waging Heavy Peace, due to be published this autumn. Secondly, he reconvened the doughty Crazy Horse to channel folk songs remembered from his youth into a scrappy, invigorating album, Americana. Finally, Young kept Ralph Molina, Billy Talbot and a notably engaged Frank Sampedro around for further sessions, that have coalesced into the 35th and longest studio album of his career: Psychedelic Pill, a remarkable series of jams that keep returning to the subject of writing a memoir.

Psychedelic Pill opens, quaintly, with a kind of acid flashback. As “Driftin’ Back” begins, Young is alone with his acoustic guitar, “dreaming about the way things sound now/Write about them in my book,” and grappling with the relationship between himself and his readers. After about 80 seconds, Crazy Horse join him for some unusually sweet, CSNY-like harmonies, but in an audacious coup de théâtre, they are gradually overwhelmed by another, electric version of the song. A looming jam on the song is faded in, midway through what proves to be one of many protean solos.

If “Driftin’ Back” is anything to go by, Waging Heavy Peace will be inventive, idiosyncratic, digressive and preposterously long. “Driftin’ Back” ebbs and flows for 27 minutes, anchored – if that’s the right word – by Ralph Molina’s highly personal interpretation of keeping time, while Young sorts through a wide selection of his most languid and mellifluous attack strategies. The best antecedent might be “Slip Away” on 1996’s undervalued Broken Arrow, an album that shares a good few similarities, at least sonically, with Psychedelic Pill. Verses here are strewn randomly across the rugged terrain, impressionistic snippets from various rants and reveries about the acts of creation and meditation, about “blocking out my anger” and, evidently, succumbing to it. “Don’t want my MP3,” he protests at one stage (somewhat ironically, given how Psychedelic Pill can only be reviewed as a digital stream), before complaining about the use of Picasso in wallpaper design. Much, much later, he will announce, bafflingly, “Gonna get me a hip-hop haircut,” and eventually conclude, more plausibly, “Finding my religion/I might be a pagan…”

As a method of repelling the sceptics, it’s hard to think of a more effective album opener than “Driftin’ Back” in anyone’s catalogue. For those faithful Rusties who relished the “Horse Back” jam – a horizontal, 37-minute extrapolation of “Fuckin’ Up” and “Cortez The Killer”, posted on neilyoung.com this January to herald the return of Crazy Horse – the good news is that Psychedelic Pill features three more new classics in that unhurried, expansive style. Two of them, “Ramada Inn” and “Walk Like A Giant”, will already be familiar to fans who’ve listened assiduously to bootlegs of the recent Crazy Horse American tour.

“Ramada Inn” (16:50) is the more tender of the pair, with an uncharacteristically nuanced and coherent narrative about a long-term relationship being tested by alcoholism. The presence in recent setlists of “Love And Only Love”, from 1990’s Ragged Glory, gives a clue as to the elegaic tone that Young conjures up with both his voice and his guitar, and the gentleness that he solicits from his traditionally rough and ready bandmates. Meanwhile, “Walk Like A Giant” (16:29; live, the Arc-style clanging finale stretches for ten more minutes) finds Young’s questing solos brought back down to earth by a jauntily whistled refrain.

The subject matter will be familiar from many of the vigorous and strange albums Young has made since Greendale in 2003 – namely, the failure of his generation to deliver on their strident promises to save the world. “I used to walk like a giant on the land,” he sings, “Now I feel like a leaf floating on the stream.” But if the lyrics allude to defeat, he manifestly still believes in the transformative possibilities of an electric guitar solo. As “Walk Like A Giant” sputters to its conclusion, he has rarely sounded so furious, and so potent.

In contrast, the fourth lengthy track, “She’s Always Dancing”, is a comparative trinket, clocking in at 8:33. Evidently delighted by “Driftin’ Back”’s opening gambit, Young repeats the trick, letting an a capella intro be consumed by another torrid and ecstatic jam, this one in the vein of “Like A Hurricane”. The protagonist, a hazily-drawn free spirit much given to “burning”, is very like the woman in the “shiny dress” who practises her “party moves” in the title track. “Psychedelic Pill” itself is pretty flimsy stuff, in which Young finds a decent riff and lets a fragment of a tune cling on to it for dear life: he even introduced it, during an August show at Red Rocks, Colorado, by admitting, “It’s a new song but it sounds exactly like an old song. I don’t even know what it is.” “Cinnamon Girl” might be the reflex answer, but an even closer analogue is “Sign Of Love” from Le Noise (2010). The thinnest song on the album, Young stubbornly plays it twice, once in a “Phased Mix” that subjects the entire track to strafing effects, presumably in a stab at psychedelic resonance, or else as a crude, homebrewed response to Daniel Lanois’ sonic gerrymandering on Le Noise.

“Twisted Road” is a good-natured amble through nostalgic reference points (“Like A Rolling Stone”, Hank Williams, Roy Orbison, “listening to the Dead on the radio”), written for what became the Le Noise sessions: Crazy Horse reportedly rehearsed it before they were dismissed in favour of Lanois’ gadgetry. “For The Love Of Man”, a heartfelt bit of schmaltz, is Psychedelic Pill’s “Hitchhiker” or “Ordinary People” – an unreleased curio plucked from the archives and revamped, for obscure reasons. Bootleg live versions of “For The Love Of Man”, often called “I Wonder Why”, date it from 1981, and it shares an inspiration – Young’s son Ben, who has cerebral palsy – with that year’s Re-Ac-Tor, if not a style.

Psychedelic Pill runs for nearly 88 minutes, across two CDs, three vinyl records, or one of Young’s beloved Blu-Ray discs. It’s the work of a man still preoccupied with concepts of liberty, who still feels the need – both spiritually and, it seems, financially – to work, but who has engineered himself into a position where he can carry out his business with extraordinary freedom. Jonathan Demme, the director who has now collaborated on three films with Young, told Jaan Uhelszki, “Before Neil had the aneurysm [in 2005] he told me he used to feel like a giant, and now he feels like a leaf in the stream… It was a watershed moment. It’s allowed him to take bigger risks.”

To some, Psychedelic Pill will seem like a monumental work of self-indulgence. To others, though, its heft and eccentricity make it one of the purest expressions of Young’s genius to date. At its centre is one last song, a cranky, boisterous little country number called “Born In Ontario”, which compresses the themes of this enthralling record into a digestible nugget distantly related to “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere”. “Born In Ontario” breezily encompasses roots, family, rough-hewn philosophy, the pursuit of freedom, life on the road, and the consolations of writing: “Once in a while, when things go wrong/ I pick up a pen, scribble on a page/Try to make sense of my inner rage.”

Like many things that Neil Young sings, it comes across as rather facile on paper. In the context of this mammoth album, though, juxtaposed against so much eloquent and emotional guitarplay, it encapsulates the joy, depth and paradox of Psychedelic Pill: an album, inspired by the writing of a book, that is at its most profound when the words are swamped by a great, irresistible weight of music.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey