The Canadian went looking for a new producer. What she found, on her fourth album, was love. The story of Voyageur is the very definition of bittersweet. Newly divorced after five years of marriage to Colin Cripps, her guitarist and bandleader, Kathleen Edwards was writing up a storm and itching to break out of the alt-country/singer-songwriter cul-de-sac. Edwards’ search for a new producer led her to the doorstep of Justin Vernon’s Wisconsin studio. Vernon took a break from his labours on this year’s Bon Iver to cut a quick track with Edwards, in order to determine whether the two had any chemistry. She chose the autumnal ballad “Wapusk”, which she’d recently written and recorded for Canada’s National Parks Project (the new version was released last September as a non-LP single). To say that the impromptu session broke the ice would be an understatement; not only did Edwards locate a simpatico co-producer in Vernon, she also found her soul mate. Vernon acknowledged their shared experience in an ardent dedication found in the Bon Iver booklet: “To Kathleen for… bringing the most peace I’ve ever felt in my life”. The album opens on a doggedly hopeful note, as, amid the exuberant, acoustic guitar-driven onrush of “Empty Threat”, Edwards anticipates a fresh start: “I hit my head ’til it bled/I pressed reset, goddammit!/I’m moving to America… It’s not an empty threat”. She’d written the song right after spending several weeks in Seattle and Portland, where she’d done some co-writing with John Roderick of the Long Winters, and though the lyric relates to that experience, it dramatically foreshadows what would subsequently go down in Wisconsin. Two songs later, on the hushed ballad “A Soft Place To Land”, she’s practically crushed under the weight of unfinished business, desperately clawing her way out of the wreckage. “Calling it quits/You think this is easy”, she asks at the top of the song, over her own mournful violin. From these thematic scene-setters, the album erupts into sustained grandeur. The blend of Edwards’ beguiling voice, sticky handcrafted melodies and sing-along refrains with Vernon’s heady arrangements is consistently intoxicating, as the moods and images continually shift between lacerating heartbreak (“A House Full Of Empty Rooms”, “Pink Champagne”) and open-hearted anticipation (the chunky, Tom Petty-style rocker “Mint”, the percolating “Sidecars”). These juxtapositions continue through the course of Voyageur, forming its psychological and its musical dynamic, posed by continual shifts between the visceral and the ethereal. The most striking moments occur when the two extremes collide on “Change The Sheets” and “Going To Hell”, with Edwards’ wounded vocals enclosed in Vernon’s pillowy sonic tapestries like a lover’s embrace. “Change The Sheets” boasts the album’s biggest hook in Edwards’ urgent chanting of “Go ahead, run, run, run, run”, as if she can’t wait for the past to recede and the future to flood over her. Though Voyageur can legitimately be seen as a companion piece to Bon Iver, Edwards’ defining characteristics have never been more dramatically present. Her alternating personas (vulnerable ingénue; ballsy chick).The Neil Young-like elliptical resonance of her lyrics. The homespun elegance of her melodies. As a divorce record, Voyageur is as brutally honest as Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out The Lights, but this is a song cycle that documents a journey from darkness toward a light at the end of the tunnel. Throughout, Vernon’s arrangements and performances come off not as an overlay to Edwards’ songs but rather as an ecstatic outgrowth of them, a literal labour of love. It’s hard to conceive of a more thrillingly romantic record than this one. Bud Scoppa Q&A Kathleen Edwards Were you consciously trying to escape the Americana/singer-songwriter pigeonhole in making this record? I look at my body of work and everything is a snapshot of who I am and where I’ve been, and I don’t think any of it’s dishonest, but at the same time I have all of these musical influences laying under the surface that I’ve never had the opportunity to get on a record: Randy Newman, John Prine, and Richard Buckner. And Wilco has been able to progress as a musical entity without having to reinvent themselves. That’s what you’ve done with Voyageur... I finally got the opportunity to work with somebody who was really committed to the idea of helping me see that through. Someone who could step in and wasn’t just gonna finish the tracks but was actually gonna work on the ideas until they were where they needed to be – for him as a producer and for me as the person, going, “I need something to be different this time, not because I’m desperate but because I haven’t done it yet”. “Empty Threat”, with its “Coming to America...” chorus, seems to anticipate what was about to happen to you. [Laughs] Yeah, it’s pretty fucked up. The going joke with my friends and family is, “Not such an empty threat, is it”? And I’m like, “Well, I couldn’t see that comin’”. INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA

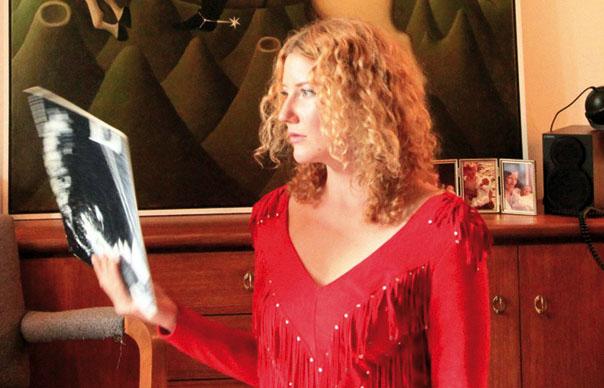

The Canadian went looking for a new producer. What she found, on her fourth album, was love.

The story of Voyageur is the very definition of bittersweet. Newly divorced after five years of marriage to Colin Cripps, her guitarist and bandleader, Kathleen Edwards was writing up a storm and itching to break out of the alt-country/singer-songwriter cul-de-sac. Edwards’ search for a new producer led her to the doorstep of Justin Vernon’s Wisconsin studio. Vernon took a break from his labours on this year’s Bon Iver to cut a quick track with Edwards, in order to determine whether the two had any chemistry.

She chose the autumnal ballad “Wapusk”, which she’d recently written and recorded for Canada’s National Parks Project (the new version was released last September as a non-LP single). To say that the impromptu session broke the ice would be an understatement; not only did Edwards locate a simpatico co-producer in Vernon, she also found her soul mate. Vernon acknowledged their shared experience in an ardent dedication found in the Bon Iver booklet: “To Kathleen for… bringing the most peace I’ve ever felt in my life”.

The album opens on a doggedly hopeful note, as, amid the exuberant, acoustic guitar-driven onrush of “Empty Threat”, Edwards anticipates a fresh start: “I hit my head ’til it bled/I pressed reset, goddammit!/I’m moving to America… It’s not an empty threat”. She’d written the song right after spending several weeks in Seattle and Portland, where she’d done some co-writing with John Roderick of the Long Winters, and though the lyric relates to that experience, it dramatically foreshadows what would subsequently go down in Wisconsin. Two songs later, on the hushed ballad “A Soft Place To Land”, she’s practically crushed under the weight of unfinished business, desperately clawing her way out of the wreckage. “Calling it quits/You think this is easy”, she asks at the top of the song, over her own mournful violin.

From these thematic scene-setters, the album erupts into sustained grandeur. The blend of Edwards’ beguiling voice, sticky handcrafted melodies and sing-along refrains with Vernon’s heady arrangements is consistently intoxicating, as the moods and images continually shift between lacerating heartbreak (“A House Full Of Empty Rooms”, “Pink Champagne”) and open-hearted anticipation (the chunky, Tom Petty-style rocker “Mint”, the percolating “Sidecars”).

These juxtapositions continue through the course of Voyageur, forming its psychological and its musical dynamic, posed by continual shifts between the visceral and the ethereal. The most striking moments occur when the two extremes collide on “Change The Sheets” and “Going To Hell”, with Edwards’ wounded vocals enclosed in Vernon’s pillowy sonic tapestries like a lover’s embrace. “Change The Sheets” boasts the album’s biggest hook in Edwards’ urgent chanting of “Go ahead, run, run, run, run”, as if she can’t wait for the past to recede and the future to flood over her.

Though Voyageur can legitimately be seen as a companion piece to Bon Iver, Edwards’ defining characteristics have never been more dramatically present. Her alternating personas (vulnerable ingénue; ballsy chick).The Neil Young-like elliptical resonance of her lyrics. The homespun elegance of her melodies. As a divorce record, Voyageur is as brutally honest as Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out The Lights, but this is a song cycle that documents a journey from darkness toward a light at the end of the tunnel. Throughout, Vernon’s arrangements and performances come off not as an overlay to Edwards’ songs but rather as an ecstatic outgrowth of them, a literal labour of love. It’s hard to conceive of a more thrillingly romantic record than this one.

Bud Scoppa

Q&A

Kathleen Edwards

Were you consciously trying to escape the Americana/singer-songwriter pigeonhole in making this record?

I look at my body of work and everything is a snapshot of who I am and where I’ve been, and I don’t think any of it’s dishonest, but at the same time I have all of these musical influences laying under the surface that I’ve never had the opportunity to get on a record: Randy Newman, John Prine, and Richard Buckner. And Wilco has been able to progress as a musical entity without having to reinvent themselves.

That’s what you’ve done with Voyageur…

I finally got the opportunity to work with somebody who was really committed to the idea of helping me see that through. Someone who could step in and wasn’t just gonna finish the tracks but was actually gonna work on the ideas until they were where they needed to be – for him as a producer and for me as the person, going, “I need something to be different this time, not because I’m desperate but because I haven’t done it yet”.

“Empty Threat”, with its “Coming to America…” chorus, seems to anticipate what was about to happen to you.

[Laughs] Yeah, it’s pretty fucked up. The going joke with my friends and family is, “Not such an empty threat, is it”? And I’m like, “Well, I couldn’t see that comin’”. INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA