The birth of the hippy dream, caught on camera... Moss carpets the floorboards, and the seats are unstuffed. A gearstick flops loose in its housing and lichens attack the murky paintswirls left on the coachwork. The camera is panning around the remains of Further, the ‘magic bus’ formerly belonging to Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, whose excursion from California to New York, ostensibly to visit the 1964 World’s Fair, has passed into underground legend. It’s not hard to see why. Many of the tropes and familiar antics of psychedelia were birthed, grooved into being – on this trip, from tie-dye T-shirts – made during an acid-fuelled stopover by a lake into which they poured tins of enamel model paint – to the prevailing sense of childlike carnivalesque that dominated proceedings. I’m reluctant to call Magic Trip a documentary, as that implies frustratingly brief bursts of archive footage interlaced with present-day talking head commentary from wise-after-the-event protags. This is different. Apart from the archaeology of the bus at the very end, the entire hour and three quarters is composed of footage from the period – making use, for the first time, of the scores of hours of 16mm footage shot by the Pranksters’ own cameraman. (Kesey & co spent the ensuing decades trying to edit it themselves but were thwarted by the volume of material and the un-synched soundtrack.) Directors Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood have reconstructed the whole trip (before, during and after), adding digressive sequences where appropriate, as well as laminating it with creative animations and graphics that illuminate rather than intrude. On the soundtrack, a mix of voiceover, recorded interviews and music tells the tale; actors read the transcribed words of deceased participants. It’s an imaginative response to a morass of material that plugs you directly into the period, places you firmly on the bus. And there’s a real scoop, as they unearth a tape of Kesey’s first LSD trial as part of the MK-ULTRA programme. The animated sequence accompanying this is brilliantly imagined, riffing off his exact words and suggesting the unlocking of mental doors. Kesey, Ken Babbs, Gretchen Fetchen and co fell between the countercultural cracks of their fast-changing times: too young to be Beatniks, too old for hippiedom. The bus contained a microcosm of the new America: a pregnant woman (Jane Burton), an exhibitionist girl (‘Stark Naked’), a cameraman (Sandy Lehmann-Haupt), an ex-Vietnam soldier (Babbs). And, behind the wheel, a goddamn liability: Neal Cassady, speed-freak, motormouth, real-life model for On The Road’s Dean Moriarty. Throughout the journey Cassady appears as a daemonic, gesticulating helmsman, forever spouting a froth of undecipherable incantations, jazz-scat and lightning-conducted Beat-nuttiness. Their uniform – a visual motif throughout – was the red stripes of the US flag; they were no enemy within, but a celebration of American vitality and frontiership. There was none of Occupy St Paul’s’s General Assembly earnestness here: decisions were taken on the hoof by the fried hive-mind. “We went wild”, says Kesey, “because we’d been caged for 50,000 years.” The Acid broke barriers. Off their nuts in Louisiana, they jump into a waterhole before it dawns on them it’s for blacks only: “Shit, we just reintegrated this place”. Such moments reveal how close they came to disaster, and film is honest about the journey’s dark side: the casualties of a free love ethic that left “the whole bus fucking” by the end of the trip as partners were exchanged and jealousies repressed; the fate of Stark Naked, committed to an insane asylum halfway along; the anticlimactic arrival in NYC, where a visibly depressed Jack Kerouac endures their forced party jollities and filming was banned from the World’s Fair. But while the film refuses to glamourise, and admits Kesey was largely finished as a creative writer and public figure afterwards, you are left with the feeling that something did change as a result of the experience, which fed into the later antics and ideology of the hippy movement (at informal ‘Acid Test’ screenings of their road movies immediately afterwards, The Grateful Dead can be seen jamming the live soundtrack). Although at times exuberant and full of delight, Magic Trip ventures beyond 60s stereotypes and reminds you that, as Kesey is heard to say, “There are some things that take precedence over enlightenment”. Rob Young

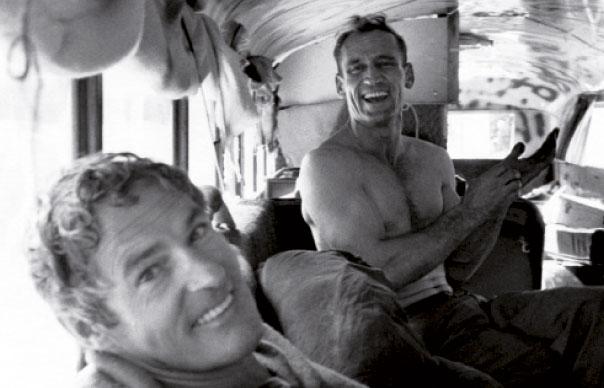

The birth of the hippy dream, caught on camera…

Moss carpets the floorboards, and the seats are unstuffed. A gearstick flops loose in its housing and lichens attack the murky paintswirls left on the coachwork. The camera is panning around the remains of Further, the ‘magic bus’ formerly belonging to Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, whose excursion from California to New York, ostensibly to visit the 1964 World’s Fair, has passed into underground legend. It’s not hard to see why. Many of the tropes and familiar antics of psychedelia were birthed, grooved into being – on this trip, from tie-dye T-shirts – made during an acid-fuelled stopover by a lake into which they poured tins of enamel model paint – to the prevailing sense of childlike carnivalesque that dominated proceedings.

I’m reluctant to call Magic Trip a documentary, as that implies frustratingly brief bursts of archive footage interlaced with present-day talking head commentary from wise-after-the-event protags. This is different. Apart from the archaeology of the bus at the very end, the entire hour and three quarters is composed of footage from the period – making use, for the first time, of the scores of hours of 16mm footage shot by the Pranksters’ own cameraman. (Kesey & co spent the ensuing decades trying to edit it themselves but were thwarted by the volume of material and the un-synched soundtrack.)

Directors Alex Gibney and Alison Ellwood have reconstructed the whole trip (before, during and after), adding digressive sequences where appropriate, as well as laminating it with creative animations and graphics that illuminate rather than intrude. On the soundtrack, a mix of voiceover, recorded interviews and music tells the tale; actors read the transcribed words of deceased participants. It’s an imaginative response to a morass of material that plugs you directly into the period, places you firmly on the bus. And there’s a real scoop, as they unearth a tape of Kesey’s first LSD trial as part of the MK-ULTRA programme. The animated sequence accompanying this is brilliantly imagined, riffing off his exact words and suggesting the unlocking of mental doors.

Kesey, Ken Babbs, Gretchen Fetchen and co fell between the countercultural cracks of their fast-changing times: too young to be Beatniks, too old for hippiedom. The bus contained a microcosm of the new America: a pregnant woman (Jane Burton), an exhibitionist girl (‘Stark Naked’), a cameraman (Sandy Lehmann-Haupt), an ex-Vietnam soldier (Babbs). And, behind the wheel, a goddamn liability: Neal Cassady, speed-freak, motormouth, real-life model for On The Road’s Dean Moriarty. Throughout the journey Cassady appears as a daemonic, gesticulating helmsman, forever spouting a froth of undecipherable incantations, jazz-scat and lightning-conducted Beat-nuttiness. Their uniform – a visual motif throughout – was the red stripes of the US flag; they were no enemy within, but a celebration of American vitality and frontiership. There was none of Occupy St Paul’s’s General Assembly earnestness here: decisions were taken on the hoof by the fried hive-mind. “We went wild”, says Kesey, “because we’d been caged for 50,000 years.”

The Acid broke barriers. Off their nuts in Louisiana, they jump into a waterhole before it dawns on them it’s for blacks only: “Shit, we just reintegrated this place”. Such moments reveal how close they came to disaster, and film is honest about the journey’s dark side: the casualties of a free love ethic that left “the whole bus fucking” by the end of the trip as partners were exchanged and jealousies repressed; the fate of Stark Naked, committed to an insane asylum halfway along; the anticlimactic arrival in NYC, where a visibly depressed Jack Kerouac endures their forced party jollities and filming was banned from the World’s Fair. But while the film refuses to glamourise, and admits Kesey was largely finished as a creative writer and public figure afterwards, you are left with the feeling that something did change as a result of the experience, which fed into the later antics and ideology of the hippy movement (at informal ‘Acid Test’ screenings of their road movies immediately afterwards, The Grateful Dead can be seen jamming the live soundtrack). Although at times exuberant and full of delight, Magic Trip ventures beyond 60s stereotypes and reminds you that, as Kesey is heard to say, “There are some things that take precedence over enlightenment”.

Rob Young