The groaning noise behind me is coming from shelves that have recently started to buckle from the almost daily addition to them of new music books, the majority of them typified by their common bulk, a shared enormity of pages, as if no band’s career can be documented in less pages than might otherwise be devoted to the history of mankind itself, from the beginning, with footnotes, anecdotal asides and a brief biography of everyone who’s ever lived. Here’s a particularly voluminous example – Johnny Rogan's Johnny Rogan's The Byrds: Requiem For The Timeless, which has been threatening to put the aforementioned shelves into a terminal gasping sag since it arrived, presumably delivered by fork-lift truck, towards the end of last year. It’s said of some books that they are too good to put down. Requiem For The Timeless is on the other hand simply too heavy to pick up, whether it’s good or not quite besides the point. At nigh on 1200 pages and as weighty as a small headstone, it’s a wrist-breaker, impossible to read without propping it on a lectern, pulpit or some other free-standing device sturdy enough to support its considerable heft. I mean, if it fell on your head, you’d be driven into the ground up to your knees at least, like some critter in a cartoon being brained by a falling anvil. In times of so-called yore, I suppose it may have been possible to tip a rickety urchin tuppence to carry it around for me. In these more civilised times, this would be rightly frowned upon as unhappy exploitation, unthinkable child labour, like the reintroduction of chimney sweeps. And I suspect it would, anyway, probably cost rather more than the farthing or two that a pasty-faced waif would have happily accepted with a gap-tooth grin and tug of a wispy forelock to pay some sullen modern teen to lug the thing around morosely in my wake, ready for perusal whenever I felt like dipping into pages. Currently next to Rogan’s Byrds’ epic on the shelves behind me is a blessedly slimmer tome of a mere 400 pages, called Will Oldham On Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, a series of interviews with Oldham conducted by the musician and writer Alan Licht. I spent an uncomfortable couple of hours with Oldham in a Camden pub in, I think, 1994, trying to get him to talk in more than vague allusion about his song-writing and career to date. A growing suspicion that he would prefer to talk about just about anything more than himself and his music was illuminatingly borne out when I turned off the tape and after another couple of drinks he mentioned that near the hotel where he was staying a cinema was showing a double bill of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia, which if he hadn’t been booked to play the Camden Monarch that evening he would definitely have gone to see. As a fellow Peckinpah fan and of the opinion, to boot, that The Wild Bunch can lay claim to being the greatest American films ever made, I was quick to engage Oldham in further conversation about Peckinpah. For the hour or so before he was called away to sound-check that’s all we talked about. Where only a little earlier, Oldham had been buttoned-up and evasive, he became instead vastly effusive, no shutting him up now, not that I would have wanted to. When he was on such a garrulous roll, Oldham clearly could be fascinating and illuminating - as he is here in a series of wide-ranging chats I spent the weekend pretty engrossed in. Also lurking behind me are several more titles I have yet to tackle, including a Gregg Allman autobiography, My Cross To Bear, which looks like a suitably ripping read. It’s reasonably slim, too, although at 400 pages not exactly anorexic. Richard King's How Soon is Now? The Madmen And Mavericks Who Made Independent Music 1975-2005, meanwhile, is rather heftier at a solid 600 pages but at first glance looks like it’ll be worth a closer read. I’ve also just received Save What You Can: The Day Of The Triffids, 500 pages of closely typeset pages devoted to the great Australian band by the photographer and writer Bleddyn Butcher, for which I am sure the words ‘labour of love’ must surely be appropriate. Also waiting to be read is a memoir by Ed Sanders, the former Fug, political activist and author of The Family, about the Manson Murders. Also just in: a new book about Townes Van Zandt to add to the two good recent Townes biographies, John Kruth’s To Live Is To Fly and A Deeper Blue by Robert Earl Hardy. This one’s called I’ll Be Here In The Morning: The Songwriting Legacy Of Townes Van Zandt by Brian T Atkinson, which collects anecdote and opinion on Townes’s songs from, among others, Guy Clark, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Dave Alvin, Josh Ritter and Michael Timmins of Cowboy Junkies, who toured with Townes in his later years. That’s a pile of words to get through, then, some of them with a bit of luck in time for the next Uncut book page. Finally, a couple of days after the last newsletter went out with reference in it to Dr Feelgood, I got an email alerting me to an online petition to have a 300 foot gold-plated statue of Lee Brilleaux erected on the seafront in Southend, near the Kursaal, where the Feelgoods often played. I had to scan the original email a couple of times to make sure I wasn’t misreading it – but, yep, sure enough, that’s what it said: a 300 foot high statue. Can’t imagine there’d be any issues over planning permission for something like that. If you’d like to sign the petition, here’s the address to go to: http://focalpoint.org.uk/e-petition Have a good week. Allan Byrds pic: Getty Images

The groaning noise behind me is coming from shelves that have recently started to buckle from the almost daily addition to them of new music books, the majority of them typified by their common bulk, a shared enormity of pages, as if no band’s career can be documented in less pages than might otherwise be devoted to the history of mankind itself, from the beginning, with footnotes, anecdotal asides and a brief biography of everyone who’s ever lived.

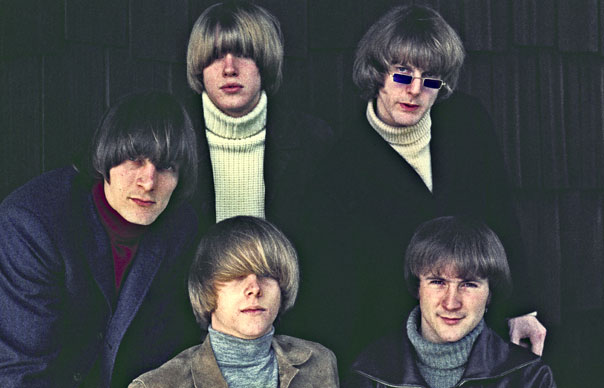

Here’s a particularly voluminous example – Johnny Rogan’s Johnny Rogan’s The Byrds: Requiem For The Timeless, which has been threatening to put the aforementioned shelves into a terminal gasping sag since it arrived, presumably delivered by fork-lift truck, towards the end of last year.

It’s said of some books that they are too good to put down. Requiem For The Timeless is on the other hand simply too heavy to pick up, whether it’s good or not quite besides the point. At nigh on 1200 pages and as weighty as a small headstone, it’s a wrist-breaker, impossible to read without propping it on a lectern, pulpit or some other free-standing device sturdy enough to support its considerable heft. I mean, if it fell on your head, you’d be driven into the ground up to your knees at least, like some critter in a cartoon being brained by a falling anvil.

In times of so-called yore, I suppose it may have been possible to tip a rickety urchin tuppence to carry it around for me. In these more civilised times, this would be rightly frowned upon as unhappy exploitation, unthinkable child labour, like the reintroduction of chimney sweeps. And I suspect it would, anyway, probably cost rather more than the farthing or two that a pasty-faced waif would have happily accepted with a gap-tooth grin and tug of a wispy forelock to pay some sullen modern teen to lug the thing around morosely in my wake, ready for perusal whenever I felt like dipping into pages.

Currently next to Rogan’s Byrds’ epic on the shelves behind me is a blessedly slimmer tome of a mere 400 pages, called Will Oldham On Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, a series of interviews with Oldham conducted by the musician and writer Alan Licht.

I spent an uncomfortable couple of hours with Oldham in a Camden pub in, I think, 1994, trying to get him to talk in more than vague allusion about his song-writing and career to date. A growing suspicion that he would prefer to talk about just about anything more than himself and his music was illuminatingly borne out when I turned off the tape and after another couple of drinks he mentioned that near the hotel where he was staying a cinema was showing a double bill of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia, which if he hadn’t been booked to play the Camden Monarch that evening he would definitely have gone to see.

As a fellow Peckinpah fan and of the opinion, to boot, that The Wild Bunch can lay claim to being the greatest American films ever made, I was quick to engage Oldham in further conversation about Peckinpah. For the hour or so before he was called away to sound-check that’s all we talked about. Where only a little earlier, Oldham had been buttoned-up and evasive, he became instead vastly effusive, no shutting him up now, not that I would have wanted to. When he was on such a garrulous roll, Oldham clearly could be fascinating and illuminating – as he is here in a series of wide-ranging chats I spent the weekend pretty engrossed in.

Also lurking behind me are several more titles I have yet to tackle, including a Gregg Allman autobiography, My Cross To Bear, which looks like a suitably ripping read. It’s reasonably slim, too, although at 400 pages not exactly anorexic. Richard King’s How Soon is Now? The Madmen And Mavericks Who Made Independent Music 1975-2005, meanwhile, is rather heftier at a solid 600 pages but at first glance looks like it’ll be worth a closer read.

I’ve also just received Save What You Can: The Day Of The Triffids, 500 pages of closely typeset pages devoted to the great Australian band by the photographer and writer Bleddyn Butcher, for which I am sure the words ‘labour of love’ must surely be appropriate.

Also waiting to be read is a memoir by Ed Sanders, the former Fug, political activist and author of The Family, about the Manson Murders. Also just in: a new book about Townes Van Zandt to add to the two good recent Townes biographies, John Kruth’s To Live Is To Fly and A Deeper Blue by Robert Earl Hardy. This one’s called I’ll Be Here In The Morning: The Songwriting Legacy Of Townes Van Zandt by Brian T Atkinson, which collects anecdote and opinion on Townes’s songs from, among others, Guy Clark, Kris Kristofferson, Lucinda Williams, Dave Alvin, Josh Ritter and Michael Timmins of Cowboy Junkies, who toured with Townes in his later years.

That’s a pile of words to get through, then, some of them with a bit of luck in time for the next Uncut book page.

Finally, a couple of days after the last newsletter went out with reference in it to Dr Feelgood, I got an email alerting me to an online petition to have a 300 foot gold-plated statue of Lee Brilleaux erected on the seafront in Southend, near the Kursaal, where the Feelgoods often played. I had to scan the original email a couple of times to make sure I wasn’t misreading it – but, yep, sure enough, that’s what it said: a 300 foot high statue. Can’t imagine there’d be any issues over planning permission for something like that.

If you’d like to sign the petition, here’s the address to go to: http://focalpoint.org.uk/e-petition

Have a good week.

Allan

Byrds pic: Getty Images