Neil Young has announced details of a special 50th anniversary reissue of his 1973 album, Time Fades Away, which will be released on November 3 via Reprise Records. Unavailable on vinyl for many years, until a much-delayed repress in 2014, Young called it his his “worst album”. But, as Allan ...

Neil Young has announced details of a special 50th anniversary reissue of his 1973 album, Time Fades Away, which will be released on November 3 via Reprise Records. Unavailable on vinyl for many years, until a much-delayed repress in 2014, Young called it his his “worst album”.

But, as Allan Jones wrote in Uncut in May 2010 (Take 156), his most elusive release is also one of his most important…

Neil Young was still laid up at his Broken Arrow ranch, just south of San Francisco, recovering from spinal surgery, when Harvest made him the biggest-selling solo artist in the world. During the long months of his recuperation, there had been a growing clamour for him to tour that had gone unanswered, although he knew there were big bucks to be made by everyone after the album’s phenomenal success. His record company had simultaneously been so hungry for a follow-up that in November 1972, they’d released the soundtrack from his unseen film, “Journey Through The Past“. It was a rag-bag of old tracks, studio outtakes, a couple of live cuts, bits of Handel’s “Messiah”, a cover of The Beach Boys’ “Let’s Go Away For Awhile” and only one new song, “Soldier”. Young hadn’t wanted it released at all, but Warners had told him they’d distribute the film if he gave them the soundtrack. They then tried to dress it up as his ‘new’ album, and promptly dumped the film.

The same month, fuming at the label’s duplicity, he anyway started to assemble a large crew of technicians at his ranch to prepare for a three-month, 65-date tour, the largest and longest of its kind to date, which would find him playing nightly to audiences of up to 20,000 people in sports stadiums, basketball arenas, ice hockey rinks. Also at Broken Arrow were The Stray Gators, the band who’d played on “Harvest”, including veteran Nashville session drummer Kenny Buttrey, bassist Tim Drummond, pedal-steel player Ben Keith and on keyboards Jack Nitzsche, the producer and arranger who’d first worked with Young on his Buffalo Springfield epic, “Expecting To Fly”. They would be his backing band on the forthcoming tour, rehearsals for which were interspersed with recording sessions for the official follow-up to Harvest.

Young had already recorded four solo acoustic demos at A&M Studios in LA – “Letter From Nam”, “Last Dance”, “Come Along And Say You Will” and “The Bridge” – and worked up more new songs at Broken Arrow. The new record’s working title was “Last Dance”. There was even a tracklisting for it that included the songs “Time Fades Away”, “New Mama”, “Come Along And Say You Will”, “The Bridge”, “Don’t Be Denied” on side one, with “Lookout Joe”, “Journey Through The Past”, “Last Dance” and “Goodbye Christians On The Shore” completing the album.

As the recordings and rehearsals continued and perhaps the scale of the tour he was about to start became increasingly apparent, Young grew ever more fretful about his physical condition. He hadn’t played electric guitar onstage since a CSNY concert in Minneapolis on July 9, 1970. For most of the past 12 months, because of his debilitating spinal condition, he’d had to wear a back brace which sometimes made playing even acoustic guitar painful, and he’d therefore made only one public appearance during the last 18 months, at the Mariposa Folk Festival in Ontario in July 1971. With the tour now looming, he began to worry that he wouldn’t be able to carry an entire show on his own. He called Danny Whitten, guitarist with his estranged former backing group, Crazy Horse, with whom he’d recorded Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. Young had once proudly described Crazy Horse as “the American Rolling Stones” and throughout his career they would be his most spectacular musical sparring partners. But because of Whitten’s chronic heroin addiction, Neil had fired the band and scrapped most of the tracks they’d recorded together for the album that became After The Gold Rush.

No-one’s properly explained why Whitten turned to heroin, but there’s always been the suspicion that it had something to do with the rejection he felt when Neil decided to divide his time between Crazy Horse, with whom he would be successful, and CSNY, with whom he became a superstar. Whatever, his life was soon one long drugs binge. His heroin habit worsened, to the point where, unable any longer to work with him, Crazy Horse fired him during rehearsals for a tour to promote their eponymous ‘solo’ LP, which Jack Nitzsche had produced in late 1970. Being sacked by his own band was a humiliation Whitten responded to by sinking ever deeper into narcotic oblivion. According to Young biographer Jimmy McDonough, he’d spend weeks on end in his apartment, sitting in his bathtub, shooting up speedballs of heroin and cocaine. When he wasn’t mainlining, he was drinking heavily.

Answering Young’s call to join him and The Stray Gators at Broken Arrow, however, Whitten told Neil he was clean, finally off heroin, and he turned up at the ranch to join the rehearsals. He was a mess, though, unable to learn his parts, and still using, according to Nitzsche. Neil had offered his friend a lifeline, a way out of drugs and back into music. But Whitten was already too far gone. On November 18, 1872, Young made a painful decision and sacked him. He gave Whitten $50 and a plane ticket back to LA, where the same night Whitten fatally overdosed on a mix of alcohol and Valium. Young was devastated. He blamed himself for Whitten’s death, slipped into a brooding funk he carried with him into the tour that followed.

“Danny’s OD put a shadow over everything,” Ben Keith tells Uncut. “But we had to forget about it. Move on. Neil had a job to do and got on with it. The show must go on, I guess.”

What became know as the Time Fades Away tour opened on January 4, 1973, at the Dane County Coliseum in Madison, Wisconsin, and it was fraught from start to finish. Young would later describe it as one of the unhappiest times of his life, probably the worst tour of his career.

He’d already fallen out with the band, over their demands for more money than they’d originally signed up for and when they weren’t onstage, travelling together on the turbo-prop Lockheed Elektra jet Young had chartered for the tour, he tended to keep his distance from them. He stayed on separate floors in hotels, retreating to his room after most shows to get drunk on tequila and stoned on pot.

After only a few shows, he became frustrated with the way the band were playing, how they sounded in the cheerless arenas into which they’d been booked. His mood was worsened by the behaviour of the crowds. They were distracted and noisy during the acoustic parts, restless and inattentive elsewhere. Most had come to hear their favourite songs from Harvest. They were noisily indifferent to anything they were unfamiliar with, which turned out to be a lot. At least a third of every show was devoted to new songs, previously unheard. These were emotionally raw and came from a much darker place than Harvest.

Young’s performances became increasingly erratic, prone to hysteria, confrontational. He took to berating audiences. More than once, enraged, he quit the stage and took the startled band with him. There were few nights when Neil didn’t throw a major strop. His moods took a toll on everyone, especially the crew, who struggled with the inadequacies of the custom-built PA and the inhospitable acoustics of the huge sheds they were playing.

Neither did the band escape his often boozy wrath.nKenny Buttrey had made his bones as a studio drummer, in which environment he had few equals. Nothing he played on tour seemed to satisfy Neil, however, and none of it was loud enough, even though he used bigger and bigger sticks and hit the drums so hard his hands bled. After 33 shows, he was replaced by Johnny Barbata, who’d played on the last CSNY tour.

“Neil called me up halfway through the tour and said, ‘Buttrey’s not making it, can you come out and play drums for me?’” Barbata tells Uncut. “Apparently, he wasn’t hitting the bass drum loud enough for Neil. Buttrey’s a studio musician, and a lot of studio musicians don’t play with any balls. I said, ‘Sure, when do you want me to come out?’ He said, ‘Tomorrow. We’ve got a show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. There’s a plane ticket waiting, they’ll pick up your drums.’ I raced to the airport, barely made my flight. I got to the hotel before Neil did, with my drums in the back of my limo. Neil said, ‘All right, Barbata. You made it.’ I don’t know what he would have done if I hadn’t. He didn’t have Buttrey. He gave me 20 minutes’ rehearsal and they recorded a song onstage that night I’d never heard before. Tim Drummond had to give me all the cues. It was pretty wild.”

By now, with a month of the tour left, Young’s voice was giving out. David Crosby and Graham Nash signed up for the last three weeks, although what they could have done to lighten the sour mood that had settled on things is unclear – Crosby’s mother was dying of cancer.

There was one more flashpoint. On March 31, the Time Fades Away tour fetched up at Oakland Coliseum, where during a version of “Southern Man”, Young saw a cop laying into a fan. “I can’t fuckin’ sing with this happening,” he announced, storming off, as the angry crowd pelted the stage with bottles.

“It was a weird night,” Barbata recalls. “He’d already done his acoustic set and we came on and did one song. A cop was hassling some girl in the front row and it pissed Neil off. He couldn’t concentrate, so he just told the band to leave the stage. He had to tell me twice, I was in shock – ‘Barbata, let’s go. Barbata, let’s go.’”

Three nights later, on April 3, in Salt Lake City, after exactly 90 days, the Time Fades Away tour was finally, to the relief of everyone, over.

Back at Broken Arrow, Young’s mood was dark. He continued to brood over Whitten’s death, which took on a symbolic significance. “It just seemed like it really stood for a lot of what was going on,” Young told Melody Maker in 1985. “It was like the freedom of the ’60s and free love and drugs and everything… it was the price tag. This is your bill. Friends, young guys dying, kids that didn’t even know what they were doing, didn’t know what they were fucking around with. It hit me pretty hard, so at that time I did sort of exorcise myself.”

Whatever he released next, in other words, would have to recognise the harsh new realities he’d recently had to face. In his present mood, the winsomeness of Harvest was far beyond him. Neither did he show much interest in returning to the tracks he’d recorded with The Stray Gators the previous November.

Early in 1971, a double live album had been announced, along with a tracklisting. It had never been released. Now, however, Young’s thoughts turned again to a live album. Elliot Mazer, who’d produced Harvest, had recorded 45 of the dates on the Time Fades Away tour and Young started to review them, discarding familiar songs in favour of the new material he’d played to an often hostile reaction from an audience who’d only wanted to hear the hits they knew.

Then as now, live LPs were often little more than contract-fillers, cash-ins, something to plug the gap when an artist had nothing new to say. Young was looking for something different and so what became the Time Fades Away album would reflect the strains, tensions and conflict of the recently completed tour, a documentary roughness, unflattering in many ways, but painfully honest, which was as much as Young could ask of himself at the time, his only reasonable response to the sombre place his world had become.

The album when it came out featured seven tracks recorded during the last month of the TFA tour, plus a 1971 live version of “Love In Mind”. It opens with the six-minute title track, a feverish narrative about junkies, politicians and the military, intercut with a running dialogue between a wayward son and his weak, pleading father. Musically, you can imagine it was perhaps intended to recall something like the lean howl of Dylan’s “Highway 61…”. Instead, it’s noisy, cantankerous, all over the place. Nitzsche’s frantic piano, high in the lop-sided mix, drowns out Young’s guitar and Ben Keith’s pedal steel. Halfway through, there’s a wheezing harmonica solo, mercifully brief. Barbata should be driving all this along with some urgency, but nobody seems to have told him where the song is going and he spends the entire number hammering away in the background like a man building a shed.

“Yonder Stands The Sinner” is no less reassuring, a demented 12-bar thrash, with Young barking the lyric like someone apparently possessed you’d walk around in the street. “LA” takes his elemental sense of right and wrong to new, wrathful limits. “When the suburbs are bombed and the freeways are crammed/And the mountains erupt and the valley is sucked/Into cracks in the earth/Will I finally be heard by you?” he rages. Uncut’s Bud Scoppa, writing about the album in Rolling Stone, compared Young’s performance here to “some neo-Israelite prophet, warning the unhearing masses of the inevitable apocalypse”.

The record’s three ballads – “Journey Through The Past”, introduced as “a song without a home”, “The Bridge” and the gorgeous “Love In Mind” – offer some respite on a record whose battered psychology is most bruisingly represented by the two long tracks that open and close its second side. “Don’t Be Denied”, written the day after Whitten’s death, is graphically autobiographical, directly descended from “Helpless”. Its four verses cover Young’s childhood, his parents’ divorce, his troubled adolescence (“The punches came fast and hard/Laying on my back in the school yard”), the corruption of youthful optimism and the redemption offered by music.

“Last Dance”, meanwhile, much changed from the original A&M sessions, opens with a blast of feedback and over the next 10 minutes becomes a thing of relentless mayhem. The song’s lyric is initially admonishing, a hippy’s ticking off of the ‘straight’ lifestyle of nine-to-five mundanity. “You can make it on your own time/Laid back and laughing,” Young sings, but he doesn’t sound terribly convinced that the alternative way of living he’s proposing is any more fulfilling than what he’s notionally criticising. His sudden acknowledgement of this is startling. The track has been in many ways limping towards a predictable end, and the band sound on the verge of packing up for the night, when from somewhere Young gets a second wind. “No, no, no,” he starts singing, hoarsely, apparently rejecting the somewhat self-righteous message of the song so far. “No… No… No…,” he goes on, screaming now. “NO! NO! NO!” There’s more feedback, the band sounding confused by what’s happening. “NONONO!!!” Young rants, out there, in a place you wouldn’t want to be for long, racking up something like 76 consecutive triple negatives. He sounds as close to being out of control as he ever will on record, or anywhere else. “Sing with us, c’mon!” you can hear Nash shouting, although you’re not sure who he’s talking to – the audience or the rest of the band. Barbata comes pounding back in about now, hauling everyone else behind him. The song ends in a kind of exhausted chaos, leaving behind it an ominous silence.

Anyone who’d sat, largely appalled, through performances like this on the Time Fades Away tour would have been astonished if you’d told them they’d soon be released on a live album as a follow-up to Harvest.

Time Fades Away was released in October ’73, to the worst reviews of Young’s career to date. “‘Time Fades Away’ proves once and for all that like so many others who get elevated to super-star status, Neil Young has now got nothing to say for himself,” opined Nick Kent in NME, a view widely shared, if spectacularly wrong.

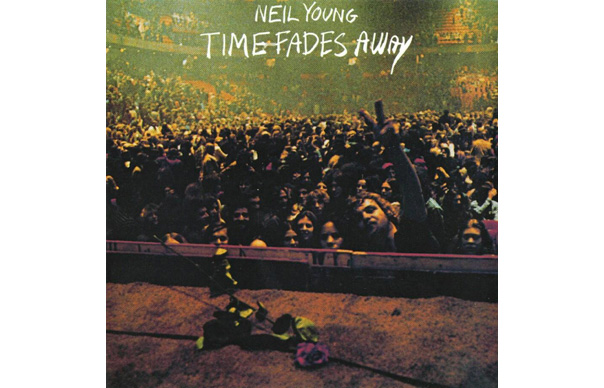

Young archivist Joel Bernstein, whose photo of the audience at Philadelphia’s Spectrum was used for the LP cover, printed on a paper stock that was intended over time to fade, summed up the bafflement of many. “How does a guy go from being the mellow hippy smiling in the barn to the drunk, intentionally out-of-it guy screaming at the audience?” he asked. “The hippy’s gone. The hippy took a plane home.”

And this is a clue to the significance of Time Fades Away. What Neil Young became, the wilful unpredictable iconoclast of subsequent legend, he started becoming here. Alone, really, of his superstar peers, he was clearly alert to the shifting mood of things and thus with Time Fades Away, he distanced himself at a stroke from the dreamy utopianism of the so-called Woodstock Nation and the sybaritic indulgence that now prevailed in the circles from which he had so dramatically with this record absented himself. Released in the same year as Raw Power, it was no less an acknowledgement that the pampered rock hierarchy of the early-’70s had had its day.

Four years before punk’s howling disenchantment, Young was already challenging the old order. By the time it came out, he had already recorded Tonight’s The Night, a tequila-soaked musical wake for Danny Whitten and CSNY guitar roadie Bruce Berry, who had recently died from a heroin OD. There would be no turning back from here.

Forty years after its release, Time Fades Away and the Journey Through The Past soundtrack are the only albums from Young’s copious back catalogue that have never been available on CD. Plans for a November 1995 CD release were scrapped at the last moment, for unexplained reasons, perhaps to do with Young’s own view of the album – “the worst record I ever made” – and the painful place in his history that it occupies. It was also conspicuously absent from the August 2003 Neil Young Archives Digital Masterpiece Series releases, which included CD debuts for On The Beach, American Stars ’N Bars, Hawks & Doves and Re-Ac-Tor. In 2007, the word from his management in reply to the continued petitioning from fans for its re-release was that a CD version remained unlikely.

More recently, though, there’s been mention of a “Time Fades Away II”, which may be included in the second volume of the Archives series, possibly an expanded edition including performances of more familiar songs played on the tour, but purposely excluded from the original album, or songs recorded on the first half of the tour, with Buttrey on drums.

It being the way with Neil, however, it could be something else entirely.

PLEASE NOTE THIS ARTICLE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2010; SINCE THEN SOME OF THE ALBUMS MENTIONED AS BEING OUT OF PRINT IN THIS PIECE HAVE BEEN REISSUED