The highlight of the week gone by, for me at least, was, of course, attending the playback of Leonard Cohen’s new album Old Ideas. Cohen was there, as you’ve no doubt heard by now, and if he had so chosen he could have kept his audience hanging on his every word for many more hours than he did. I’ve already written about the vent, but it seemed also timely to revisit this piece, written originally for my Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before column in Uncut, about meeting Cohen in somewhat unusual circumstances in June 1974. A few weeks after I join the hallowed ranks of what used to be Melody Maker I’m on my own one afternoon in the office. Everyone else is either being wined and dined at some no doubt lavish record company lunch, of which in those days there were plenty, or down the pub getting pissed - a daily ritual for the paper’s sub-editors. The common feeling among the senior staff at Melody Maker at the time of which I’m writing is that my recent appointment by editor Ray Coleman is either further evidence of Ray’s unravelling sanity or the result of a ghastly administrative error. To the horror especially of uncommonly suave assistant editor Michael Watts – famed in the MM office for his cravats, safari suits and gourmet luncheons – I can barely type and think ‘shorthand’ is a nickname for Eric Clapton. “If you’re still here by the end of the month, it’ll be a miracle,” Mick informs me on my first day. For the next couple of weeks he throws me scraps. It’s not quite what I expected and I’m beginning to feel like I’m being groomed for an early exit. Fucking cheers, Mick. Anyway, I’m dropping off something at Mick’s empty desk when his phone rings and doesn’t stop for about five minutes, someone clearly with urgent things to discuss with the absent assistant editor. I pick up the phone. It’s someone from CBS about an interview with Leonard Cohen – Leonard Cohen! - Mick’s been trying to set up since shortly before fire was invented. Can I now tell Mick that Cohen’s currently at a hotel in Chelsea and is happy to meet him tomorrow? I’m given a time and address, which I promise to pass onto Mick, dutiful servant that I am. Except that I don’t tell Mick anything about the call and instead turn up myself for the interview, feeling as a long-time fan about to meet one of his heroes slightly weak in the region of my knees as I tap lightly on his hotel door, which now opens. “I’m Leonard Cohen,” Leonard Cohen – Leonard Cohen! - announces with a warm smile, a handsome man, impeccably dressed in a smart grey suit. “Welcome.” He invites me into his modest room, windows overlooking Sloane Square, flowers on a small table. I notice now that he’s barefooted. He takes a seat, feet on the bed. I remind him that the last time he appeared in Melody Maker, remarks he’d made about his own low opinion of his music had been luridly accompanied by headlines announcing his retirement. Since he is in London finishing an album he tells me will be called either New Skin For The Old Ceremony or Return Of the Broken Down Nightingale, he’s clearly not retired. What’s the story? “I have read over the years so much negative criticism of my work and of my position, so much satire, so much humorous indifference to where I stand,” he says, “that on the public level and in social intercourse with strangers I tend to dismiss myself and not take my work very seriously. “I think that interview was just a way of saying goodbye for a while, a temporary cheerio, nothing tragic. I seem, however, to have given this impression to people that I’ve been recovering from some serious illness, which I am happy to say has not been the case. “The image I’ve been able to gather of myself from the press is of a victim of the music industry, a poor sensitive chap who has been destroyed by the very forces he started out to utilise. But that is not so, never was. I don’t know how that ever got around. I would also contest the notion that I am or was a depressed and extremely frail individual also that I am sad all the time. “There is a perception, too, of my songs as depressing, but I think that’s not the case. One side of the third album I find a little burdened and melodramatic. I think that’s the fault of the songs and of the singer. It’s a failure of that particular album, but it’s not a characteristic of the work as a whole.” It seemed to me, and I hoped not fancifully, that his music was less ‘depressing’ than emblematic of an urgent inclination to create art that was fit for a world in which people died and calamity was wholesale, in which circumstance it would hardly be cheerful. “I’m very pleased with that observation,” he says. “That is definitely the most important aesthetic question of these days. Can art or what we call entertainment confront or incorporate the experience of man today? There’s a lot of evidence for a negative answer. I skirt around that question myself, very often. One feels often inadequate in the face of massacre, disaster and human humiliation. What, you think, am I doing, singing a song at a time like this? But the worse it gets, the more I find myself picking up a guitar and playing that song. “It is, I think, a matter of tradition. You have a tradition on the one hand that says if things are bad we should not dwell on the sadness, that we should play a happy song, a merry tune. Strike up the band and dance the best we can, even if we are suffering from concussion. “And then there’s another tradition, and this is a more Oriental or Middle Eastern tradition, which says that if things are really bad the best thing to do is sit by the grave and wail, and that’s the way you are going to feel better. “I think both these efforts are intended to lift the spirit. And my own tradition, which is the Herbraic tradition, suggests that you sit next to the disaster and lament. The notion of the lamentation seemed to me to be the way to do it. You don’t avoid the situation - you throw yourself into it, fearlessly.” Before I go, I ask him to sign my copy of his novel Beautiful Losers. He takes the book and looks at it, as if he hasn’t seen one in a while, notices a passage I’ve underlined and reads it aloud. “’How can I begin anything new with all of yesterday inside me. . .how can I exist as the vessel of yesterday’s slaughter?’ Not bad,” he laughs. “I wonder,” he smiles, returning the book and walking me to the door, “who I was when I wrote that.” There’s hell to pay, by the way, when I get back to the office.

The highlight of the week gone by, for me at least, was, of course, attending the playback of Leonard Cohen’s new album Old Ideas. Cohen was there, as you’ve no doubt heard by now, and if he had so chosen he could have kept his audience hanging on his every word for many more hours than he did. I’ve already written about the vent, but it seemed also timely to revisit this piece, written originally for my Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before column in Uncut, about meeting Cohen in somewhat unusual circumstances in June 1974.

A few weeks after I join the hallowed ranks of what used to be Melody Maker I’m on my own one afternoon in the office. Everyone else is either being wined and dined at some no doubt lavish record company lunch, of which in those days there were plenty, or down the pub getting pissed – a daily ritual for the paper’s sub-editors.

The common feeling among the senior staff at Melody Maker at the time of which I’m writing is that my recent appointment by editor Ray Coleman is either further evidence of Ray’s unravelling sanity or the result of a ghastly administrative error. To the horror especially of uncommonly suave assistant editor Michael Watts – famed in the MM office for his cravats, safari suits and gourmet luncheons – I can barely type and think ‘shorthand’ is a nickname for Eric Clapton.

“If you’re still here by the end of the month, it’ll be a miracle,” Mick informs me on my first day. For the next couple of weeks he throws me scraps. It’s not quite what I expected and I’m beginning to feel like I’m being groomed for an early exit. Fucking cheers, Mick.

Anyway, I’m dropping off something at Mick’s empty desk when his phone rings and doesn’t stop for about five minutes, someone clearly with urgent things to discuss with the absent assistant editor. I pick up the phone. It’s someone from CBS about an interview with Leonard Cohen – Leonard Cohen! – Mick’s been trying to set up since shortly before fire was invented. Can I now tell Mick that Cohen’s currently at a hotel in Chelsea and is happy to meet him tomorrow? I’m given a time and address, which I promise to pass onto Mick, dutiful servant that I am.

Except that I don’t tell Mick anything about the call and instead turn up myself for the interview, feeling as a long-time fan about to meet one of his heroes slightly weak in the region of my knees as I tap lightly on his hotel door, which now opens.

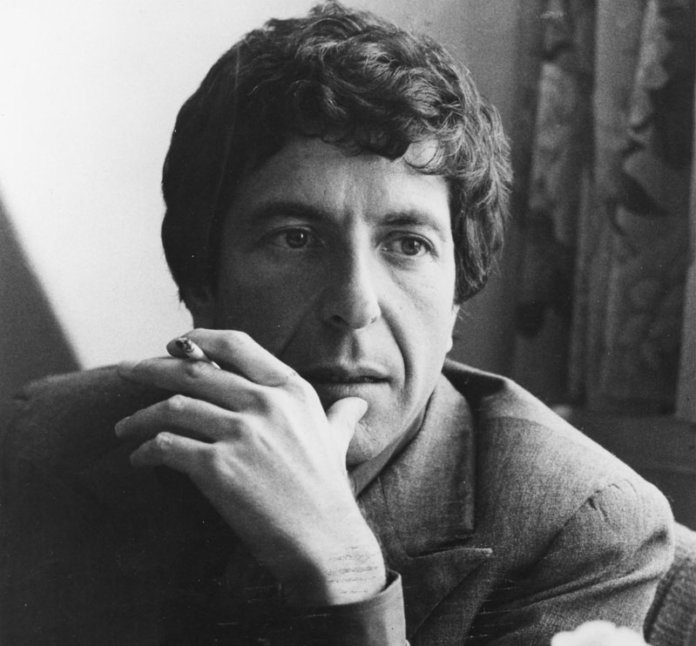

“I’m Leonard Cohen,” Leonard Cohen – Leonard Cohen! – announces with a warm smile, a handsome man, impeccably dressed in a smart grey suit. “Welcome.”

He invites me into his modest room, windows overlooking Sloane Square, flowers on a small table. I notice now that he’s barefooted. He takes a seat, feet on the bed.

I remind him that the last time he appeared in Melody Maker, remarks he’d made about his own low opinion of his music had been luridly accompanied by headlines announcing his retirement. Since he is in London finishing an album he tells me will be called either New Skin For The Old Ceremony or Return Of the Broken Down Nightingale, he’s clearly not retired. What’s the story?

“I have read over the years so much negative criticism of my work and of my position, so much satire, so much humorous indifference to where I stand,” he says, “that on the public level and in social intercourse with strangers I tend to dismiss myself and not take my work very seriously.

“I think that interview was just a way of saying goodbye for a while, a temporary cheerio, nothing tragic. I seem, however, to have given this impression to people that I’ve been recovering from some serious illness, which I am happy to say has not been the case.

“The image I’ve been able to gather of myself from the press is of a victim of the music industry, a poor sensitive chap who has been destroyed by the very forces he started out to utilise. But that is not so, never was. I don’t know how that ever got around. I would also contest the notion that I am or was a depressed and extremely frail individual also that I am sad all the time.

“There is a perception, too, of my songs as depressing, but I think that’s not the case. One side of the third album I find a little burdened and melodramatic. I think that’s the fault of the songs and of the singer. It’s a failure of that particular album, but it’s not a characteristic of the work as a whole.”

It seemed to me, and I hoped not fancifully, that his music was less ‘depressing’ than emblematic of an urgent inclination to create art that was fit for a world in which people died and calamity was wholesale, in which circumstance it would hardly be cheerful.

“I’m very pleased with that observation,” he says. “That is definitely the most important aesthetic question of these days. Can art or what we call entertainment confront or incorporate the experience of man today? There’s a lot of evidence for a negative answer. I skirt around that question myself, very often. One feels often inadequate in the face of massacre, disaster and human humiliation. What, you think, am I doing, singing a song at a time like this? But the worse it gets, the more I find myself picking up a guitar and playing that song.

“It is, I think, a matter of tradition. You have a tradition on the one hand that says if things are bad we should not dwell on the sadness, that we should play a happy song, a merry tune. Strike up the band and dance the best we can, even if we are suffering from concussion.

“And then there’s another tradition, and this is a more Oriental or Middle Eastern tradition, which says that if things are really bad the best thing to do is sit by the grave and wail, and that’s the way you are going to feel better.

“I think both these efforts are intended to lift the spirit. And my own tradition, which is the Herbraic tradition, suggests that you sit next to the disaster and lament. The notion of the lamentation seemed to me to be the way to do it. You don’t avoid the situation – you throw yourself into it, fearlessly.”

Before I go, I ask him to sign my copy of his novel Beautiful Losers. He takes the book and looks at it, as if he hasn’t seen one in a while, notices a passage I’ve underlined and reads it aloud.

“’How can I begin anything new with all of yesterday inside me. . .how can I exist as the vessel of yesterday’s slaughter?’ Not bad,” he laughs. “I wonder,” he smiles, returning the book and walking me to the door, “who I was when I wrote that.”

There’s hell to pay, by the way, when I get back to the office.