Among the extensive interviews that punctuate Living In The Material World, the bluntest assessment of George Harrison comes from Ringo Starr: “He was a bag of beads and a bag of anger.” The contradictions that ran through Harrison are well known – the multi-millionaire who preached detachment from materialism, the green gardener who loved sports cars, the spiritual seeker with a coke habit – but the four hours of Martin Scorsese’s biography hammer them home. Scorsese, a Catholic boy fascinated by gangsterdom, clearly recognises a fellow conflicted soul. Like No Direction Home, Scorsese’s 2005 portrait of Dylan, …Material World comes with a wealth of unseen material that includes home movies and letters, and is similarly split into two parts: basically, the 1960s and everything else. It’s some achievement to make The Beatles’ story fresh, but Scorsese does so, partly by taking George’s undervalued side, but mostly via an assemblage that hurtles us with visceral force from Hamburg (“the naughtiest city in the world,” recalls George) through the craziness of Beatlemania. The Fabs’ acid phase is recounted in part by Joan Taylor, the wife of Beatle PR Derek, who lucidly describes “sitting in an English garden waiting for the sun” with George and John. Home footage of Lennon peering perilously over a dizzy sea cliff tells another part of the tale. On his first trip George heard a whisper in his head, “The Yogis of the Himalayas”. Shortly afterwards he met Ravi Shankar (neither yogi nor from the Himalayas), who was to exert a profound influence on the 23-year-old Beatle: “He was the first person who impressed me.” George’s love affair with India, which never ended, continued via the Maharishi and the Krishna movement. Burnt-out by Beatledom, Harrison credits Shankar with helping him reconnect to his public, and with triggering the Concert For Bangladesh, an early act of rock philanthropy that looks a more impressive achievement in hindsight. Harrison’s post-Beatle career is treated with a mix of hagiographic respect and discreet intrigue. Once the songwriting dam had burst with All Things Must Pass, the musical delights were patchy, but the drama of his personal life compensates. Infamously there was Eric Clapton’s courtship of his wife Pattie Boyd (‘Slowhand’ ties himself in knots explaining it, talking of his “amateur inroads into what was going on in their marriage”). George’s fling with Ringo’s first wife goes unmentioned, as does a later dalliance with Lory Del Santo, once Clapton’s partner. George’s second wife, Olivia (who co-produced the movie) somehow kept their marriage stable – “George liked women and women liked George,” she admits. His fondness for cocaine likewise gets the curtest of nods – “he got heavily into drugs,” proffers Klaus Voormann sadly, “He was an extreme character.” George’s extremism manifested in his passion for motor racing – he and champion driver Jackie Stewart became friends – and in his willingness to bankroll Monty Python’s The Life Of Brian by mortgaging his beloved gothic pile in Surrey. “He wanted to see the film,” says Eric Idle. “It’s still the most anyone has ever paid for a cinema ticket.” It’s tempting to see George’s involvement with the Krishnaites, the Pythons and The Traveling Wilburys as a search for the lost group camraderie of The Beatles, but he also became an obsessed gardener, turning his Friar Park home into a home counties Eden, and doted on his son Dhani, who is a measured, charming presence in …Material World. After the shocking attack on him at his home (recounted vividly by Olivia), George understandably went off radar – he was already diagnosed with cancer, and the assault “took years off his life” reckons Dhani. The Hindu attitude to death as a transition rather than an end softens the blow of his death. Olivia considers her husband’s extremism as working out good and bad karma. Others might reckon he just did what the heck he liked. At the credits, George remains an enigma. What resonates, along with some magnificently deployed music, is the love he inspired in fans and friends. EXTRAS: None. Neil Spencer Picture credit: Mike McCartney

Among the extensive interviews that punctuate Living In The Material World, the bluntest assessment of George Harrison comes from Ringo Starr: “He was a bag of beads and a bag of anger.”

The contradictions that ran through Harrison are well known – the multi-millionaire who preached detachment from materialism, the green gardener who loved sports cars, the spiritual seeker with a coke habit – but the four hours of Martin Scorsese’s biography hammer them home. Scorsese, a Catholic boy fascinated by gangsterdom, clearly recognises a fellow conflicted soul.

Like No Direction Home, Scorsese’s 2005 portrait of Dylan, …Material World comes with a wealth of unseen material that includes home movies and letters, and is similarly split into two parts: basically, the 1960s and everything else. It’s some achievement to make The Beatles’ story fresh, but Scorsese does so, partly by taking George’s undervalued side, but mostly via an assemblage that hurtles us with visceral force from Hamburg (“the naughtiest city in the world,” recalls George) through the craziness of Beatlemania.

The Fabs’ acid phase is recounted in part by Joan Taylor, the wife of Beatle PR Derek, who lucidly describes “sitting in an English garden waiting for the sun” with George and John. Home footage of Lennon peering perilously over a dizzy sea cliff tells another part of the tale. On his first trip George heard a whisper in his head, “The Yogis of the Himalayas”. Shortly afterwards he met Ravi Shankar (neither yogi nor from the Himalayas), who was to exert a profound influence on the 23-year-old Beatle: “He was the first person who impressed me.”

George’s love affair with India, which never ended, continued via the Maharishi and the Krishna movement. Burnt-out by Beatledom, Harrison credits Shankar with helping him reconnect to his public, and with triggering the Concert For Bangladesh, an early act of rock philanthropy that looks a more impressive achievement in hindsight.

Harrison’s post-Beatle career is treated with a mix of hagiographic respect and discreet intrigue. Once the songwriting dam had burst with All Things Must Pass, the musical delights were patchy, but the drama of his personal life compensates. Infamously there was Eric Clapton’s courtship of his wife Pattie Boyd (‘Slowhand’ ties himself in knots explaining it, talking of his “amateur inroads into what was going on in their marriage”). George’s fling with Ringo’s first wife goes unmentioned, as does a later dalliance with Lory Del Santo, once Clapton’s partner. George’s second wife, Olivia (who co-produced the movie) somehow kept their marriage stable – “George liked women and women liked George,” she admits. His fondness for cocaine likewise gets the curtest of nods – “he got heavily into drugs,” proffers Klaus Voormann sadly, “He was an extreme character.”

George’s extremism manifested in his passion for motor racing – he and champion driver Jackie Stewart became friends – and in his willingness to bankroll Monty Python’s The Life Of Brian by mortgaging his beloved gothic pile in Surrey. “He wanted to see the film,” says Eric Idle. “It’s still the most anyone has ever paid for a cinema ticket.”

It’s tempting to see George’s involvement with the Krishnaites, the Pythons and The Traveling Wilburys as a search for the lost group camraderie of The Beatles, but he also became an obsessed gardener, turning his Friar Park home into a home counties Eden, and doted on his son Dhani, who is a measured, charming presence in …Material World. After the shocking attack on him at his home (recounted vividly by Olivia), George understandably went off radar – he was already diagnosed with cancer, and the assault “took years off his life” reckons Dhani.

The Hindu attitude to death as a transition rather than an end softens the blow of his death. Olivia considers her husband’s extremism as working out good and bad karma. Others might reckon he just did what the heck he liked. At the credits, George remains an enigma. What resonates, along with some magnificently deployed music, is the love he inspired in fans and friends.

EXTRAS: None.

Neil Spencer

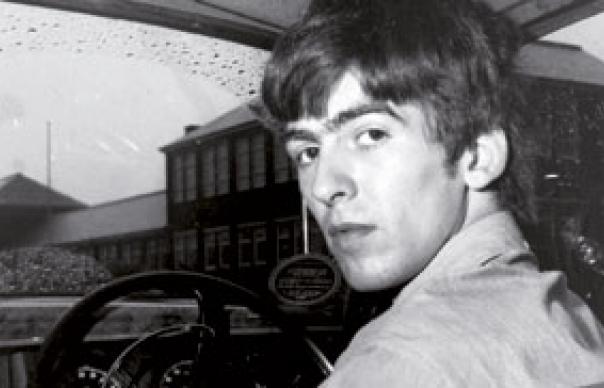

Picture credit: Mike McCartney