The term “R&B” has, in the 21st century, almost entirely lost its meaning. It’s a tidy, lazy, convenient catch-all that acts as an umbrella for any artist with the vaguest notion of music that contains elements of either “rhythm” or “blues”. It wasn’t always that way; not when the phrase was first coined in 1953 by a jobbing New York Jewish songwriter and all-round chancer called Jerry Wexler. He may be best remembered to some as the man who green-lit the signing of Led Zeppelin to Atlantic Records in 1968, but his ultimate legacy is arguably his role in bringing black music to the (white) masses without sacrificing its honesty or intentions. As a showbiz writer for Billboard magazine in the early 1950s, he championed jazz artists and didn’t much care for young upstarts who he considered were diluting the form – indeed, his use of the words “rhythm and blues” was initially considered derogatory or dismissive, rather than the heralding of any new innovation. But his Bronx “moxie” attracted the attention of fledgling mogul Ahmet Ertegun, who invited him into the Atlantic empire as both a writer and producer, his first successes coming with Ray Charles, The Drifters and Ruth Brown. Wexler was a “suit” with soul, a businessman who knew the worth of a penny but would instinctively roll on a smart gamble. Rather than throw money at a project, he pondered on whether it might reap results by denying it access to all the toys in the box. Aretha Franklin had been making records for eight years before Jerry stripped away the elaborate orchestrations of her cheesy balladry and focused on the heart-wrenching and musically naked vulnerability of “I Never Loved A Man (The Way That I Love You)”. His work with Wilson Pickett, never the household name he should have been, was undeniably influential. Wexler once hinted that he wanted to produce a soul man with “balls intact – like Marvin Gaye ought to be”, which inadvertently led to Gaye rethinking his career and focusing more on the introspective, weighty concerns of What’s Going On, as opposed to the pop fluff Berry Gordy at Motown was steering him towards. Wexler’s blend of passion and pragmatism opened doors for industry figures as diverse as Andrew Loog Oldham in The Rolling Stones’ camp or Chas Chandler, the jobbing Geordie bassist who helped catapult Jimi Hendrix to superstar status. He risked his job by facing off against both Ertegun and engineer-on-the-rise Barry Beckett over where the careers of Franklin and surprise Brit contender Dusty Springfield should be heading, but from such friction is great music made. While still vociferously proclaiming the brilliance of a rock monster like Zeppelin, he was subtly, behind-the-scenes, cajoling nervous songwriter Carole King towards becoming a performer and delivering her era-defining masterpiece Tapestry. Though not credited as producer, he was, in King’s own words, instrumental in her finding her “voice”. He was on hand to midwife Dylan’s musical (at least) conversion to Christianity on 1979’s Slow Train Coming, again as an almost shamanistic figure with whom the artist could connect to dissect every nuance of the sound and lyric. Mark Knopfler, who played on the album sessions, once claimed that Wexler was perhaps the closest Dylan ever came to embracing a collaborator. Wexler retired in the late 1990s, not long after his 80th birthday. Ever the consummate music man, when asked, in his twilight years, what he’d like written on his tombstone, his response was “Two words: more bass”. TERRY STAUNTON

The term “R&B” has, in the 21st century, almost entirely lost its meaning. It’s a tidy, lazy, convenient catch-all that acts as an umbrella for any artist with the vaguest notion of music that contains elements of either “rhythm” or “blues”.

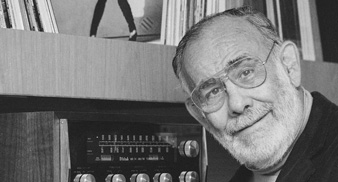

It wasn’t always that way; not when the phrase was first coined in 1953 by a jobbing New York Jewish songwriter and all-round chancer called Jerry Wexler. He may be best remembered to some as the man who green-lit the signing of Led Zeppelin to Atlantic Records in 1968, but his ultimate legacy is arguably his role in bringing black music to the (white) masses without sacrificing its honesty or intentions.

As a showbiz writer for Billboard magazine in the early 1950s, he championed jazz artists and didn’t much care for young upstarts who he considered were diluting the form – indeed, his use of the words “rhythm and blues” was initially considered derogatory or dismissive, rather than the heralding of any new innovation.

But his Bronx “moxie” attracted the attention of fledgling mogul Ahmet Ertegun, who invited him into the Atlantic empire as both a writer and producer, his first successes coming with Ray Charles, The Drifters and Ruth Brown.

Wexler was a “suit” with soul, a businessman who knew the worth of a penny but would instinctively roll on a smart gamble. Rather than throw money at a project, he pondered on whether it might reap results by denying it access to all the toys in the box. Aretha Franklin had been making records for eight years before Jerry stripped away the elaborate orchestrations of her cheesy balladry and focused on the heart-wrenching and musically naked vulnerability of “I Never Loved A Man (The Way That I Love You)”.

His work with Wilson Pickett, never the household name he should have been, was undeniably influential. Wexler once hinted that he wanted to produce a soul man with “balls intact – like Marvin Gaye ought to be”, which inadvertently led to Gaye rethinking his career and focusing more on the introspective, weighty concerns of What’s Going On, as opposed to the pop fluff Berry Gordy at Motown was steering him towards.

Wexler’s blend of passion and pragmatism opened doors for industry figures as diverse as Andrew Loog Oldham in The Rolling Stones’ camp or Chas Chandler, the jobbing Geordie bassist who helped catapult Jimi Hendrix to superstar status. He risked his job by facing off against both Ertegun and engineer-on-the-rise Barry Beckett over where the careers of Franklin and surprise Brit contender Dusty Springfield should be heading, but from such friction is great music made.

While still vociferously proclaiming the brilliance of a rock monster like Zeppelin, he was subtly, behind-the-scenes, cajoling nervous songwriter Carole King towards becoming a performer and delivering her era-defining masterpiece Tapestry. Though not credited as producer, he was, in King’s own words, instrumental in her finding her “voice”.

He was on hand to midwife Dylan’s musical (at least) conversion to Christianity on 1979’s Slow Train Coming, again as an almost shamanistic figure with whom the artist could connect to dissect every nuance of the sound and lyric. Mark Knopfler, who played on the album sessions, once claimed that Wexler was perhaps the closest Dylan ever came to embracing a collaborator.

Wexler retired in the late 1990s, not long after his 80th birthday. Ever the consummate music man, when asked, in his twilight years, what he’d like written on his tombstone, his response was “Two words: more bass”.

TERRY STAUNTON