Five CD, 91 track bonanza from reggae’s golden age... In February 1978 the Punky Reggae Party that Bob Marley would shortly celebrate in song was just getting going. To help fuel it came a mission to Jamaica comprised of several London faces; Sex Pistols’ frontman John Lydon, DJ and film maker ...

Five CD, 91 track bonanza from reggae’s golden age…

In February 1978 the Punky Reggae Party that Bob Marley would shortly celebrate in song was just getting going. To help fuel it came a mission to Jamaica comprised of several London faces; Sex Pistols’ frontman John Lydon, DJ and film maker Don Letts, photographer Dennis Morris and journalist Vivien Goldman, a quartet met at Kingston airport by Virgin boss Richard Branson in a vintage Rolls Royce to carry them to the Sheraton hotel, where Branson had booked an entire floor. The mission statement was simple; to sign up as much of the island’s musical talent as possible. For the next fortnight the Sheraton was besieged by singers and players eager for a contract.

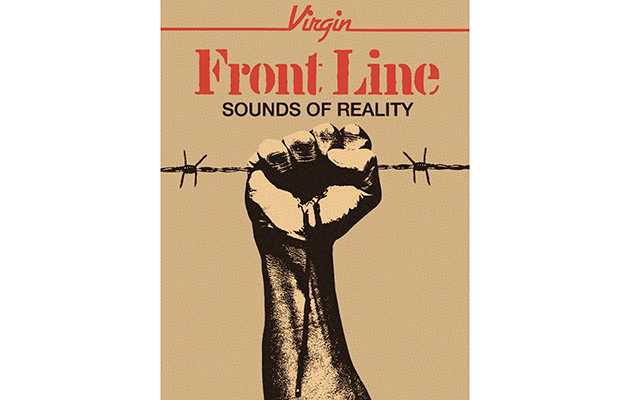

Such was the birth of Virgin’s Front Line label, launched that summer with a torrent of albums by some of reggae’s finest acts; harmony trios like Culture, The Mighty Diamonds and The Gladiators, ‘toasters’ like U Roy, I Roy, Tapper Zukie and Prince Far I, and singers like Gregory Isaacs and Johnny Clarke, augmented by UK acts like Linton Johnson and Delroy Washington.

To gather so much talent was an astonishing coup, and to market it with a pizazz reserved for rock and soul acts almost as remarkable (although Island records had already overseen the ascent of Bob Marley to superstardom). The Front Line logo of a hand clenching barbed wire was a debatable calling card – the music was more often about the spiritual aspirations of Rasta or plain old romance than political struggle – but punk and reggae shared a mood of fevered, exhilarating revolution.

The five CDs here do a commendable job of sampling what Branson’s sack of cash purchased, while the accompanying booklet includes evocative photos, press clips, capsule profiles of the acts and a funny, gracious foreword from Lydon: “It was all so inspiring. I loved it and Jamaica became part of me”.

The sheer profusion of names that were signed meant an inevitably uneven quality. Amo the most enduring tracks are those by The Gladiators, who, like others, recut old hits anew that gained in clarity and force from the originals. “Looks Is Deceiving” and “Chatty Chatty Mouth” remain tough expressions of Rasta righteousness, tinged with mystery and the millennial mood of the era when the “Two Sevens Clash” (ie1977) as Culture put it. That particular track isn’t here, but the latter trio’s anthem “Natty Never Get Weary” is still brightly engaging. The brilliance and purity of the singing on display here is often breathtaking. Jamaica had inherited its vocal tastes from the likes of Marvin Gaye and harmony groups like The Impressions, and the island became the repository of the ‘soul’ tradition. The languid tones of Gregory ‘Cool Ruler’ Isaacs are emblematic – his “Let’s Dance” and “Soon Forward” are here – but the falsetto of Johnny Clarke is similarly seductive, and the purity and agility of Norman Grant, lead voice with The Twinkle Brothers was effective whether on a love call like “Don’t Want To Be Lonely” or a militant side like “Africa”.

At the other end of the vocal scale is the concrete mixer delivery of Prince Far I, one of several ‘talk-over’ DJs present. More expressive than Far I are U Roy, the pioneer of the style, and Big Youth, whose “The Upful One” lives up to its title, and the idiosyncratic Tapper Zukie, whose “She Want A Phensic” is a barbed sexual jibe. Rapping before hip-hop made its appearance, the ‘DJs’ were true traiblazers.

Rastafari’s utopian vision of Africa was often fanciful and came mixed up with biblical prophecy, but reggae’s championship of the stuggle against apartheid in South Africa was unflagging – see The Abyssinians’ “South Africa Enlistment” or Zukie’s “Tribute To Steve Biko”.

Not everything on Front Line was rightous and rootsical. The label’s biggest hit was “Uptown Top Ranking” by Althea and Donna, two uptown girls on a lark, who have a couple of likewise lightweight cuts here. Amid a sprinkling of single selections in the mix a stand-out is the smoky “Cairo” by Joyella Blade, combining passionate vocals with early synth; another in a boxful of great voices.

Neil Spencer

Q&A

DON LETTS

What was your role on that trip?

To lend moral support, because at home John was Public Enemy Number One. It was an escape from the media frenzy. Contrary to the ‘Roxy Club DJ turned white people onto reggae’ line, John already knew the music. I had never been to Jamaica. It remains the most remarkable journey of my life.

In what way?

Meeting people who were mythic, romanticised names, and finding they were people begging us for food and drink. John and I went on forays round the island, to U Roy’s sound system for example, where we got so blitzed we crashed through the whole event. Or going to Lee Perry’s studio and watching him record “Holidays In The Sun” and ”Belsen Was A Gas’ – those tapes exist somewhere!

Any other encounters?

Meeting Tapper Zukie in Reema, a dangerous area. When John asked ‘Where all these guns then?’ his posse pulled them out. It was election time, and we were told, ’Don’t hire a green or red car’ – don’t show allegaiance. Also through the late Dicky Jobson we visited Joni Mitchell, who had a house there, and she played us some music which John asked her to take off. ’What is that shit? ‘Oh That’s my latest album’- the first time I saw John turm red.

What about the music you brought back?

It’s very special, the last golden moments of roots reggae.

Any favourites?

I can’t separete them, roots and rudie. People say Jamaica is double-edged, for some a paradise, for others a pair of dice. What reggae got

from it was exposure, and it went on to colonise the planet.

INTERVIEW: NEIL SPENCER