The past, present and future intertwine on the veteran’s latest effort... For writer/artists of a certain age, the sands of time can be like quicksand, sucking them under as they grasp at their past achievements. John Hiatt is one of the handful of exceptions to this entropic pattern; at age 61, he’s as prolific, expressive and energetic as ever, demonstrating that a gifted songwriter who’s dialed into the process of aging can continue to find fertile subject matter. Hiatt hasn’t allowed himself to be trapped in the shadow of his 1987 classic Bring The Family, his inspired collaboration with Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe and Jim Keltner, which could’ve been the hellhound on his tail if he’d succumbed to an ever more desperate need to try and match it, like so many of his contemporaries; instead, he’s kept plugging away as an indie artist, taking life as it comes. His postmillennial output – nine albums in 14 years, each one of them with its own distinct character and brace of memorable songs – has actually outpaced his rate of productivity on several major labels in the first quarter century of his career. Hiatt’s recent work has yielded some particularly impressive LPs. 2003’s Beneath This Gruff Exterior, produced by the late, great Don Smith (Petty, Wilburys) finds Louisiana slide wizard Sonny Landreth letting rip. Master Of Disaster (2005), had roots legend Jim Dickinson at the console and the North Mississippi All Stars, featuring Dickinson’s sons, providing the shit-kicking vibe. On 2008’s self-produced Same Old Man, a burnished, elegiac song cycle focused on the ups and downs of a long-term relationship, leading to some of the veteran artist’s most emotionally authentic performances. Although Hiatt has been clean since 1985, leading a quiet life with his wife and kids outside of Nashville, recollections of his wild years have continued to provide him with grist for the songwriting mill. “Mistakes are to be highlighted,” he noted in 2008. “You can’t have the light without the dark.” That duality permeates the new Terms Of My Surrender. Its songs are blues-based reflections recalling the sauntering grooves of J.J. Cale, the gritty swamp rock of Tony Joe White and Bob Dylan’s Modern Times throughout. Hiatt keeps things close to the bone, using his touring band, with guitarist Doug Lancio doubling as producer, and basing the predominantly understated performances around his lived-in voice, acoustic guitar and harmonica. In the middle of opening track “Long Time Comin’” Lancio unleashes thunderbolts with a powerfully evocative guitar solo that emphatically amplifies the intensity of the lyric, evoking Daniel Lanois’ atmospheric eruptions on Emmylou Harris’s Wrecking Ball. Hiatt goes down to the crossroads on the 12-bar blues “Face of God” and treks to Cold Mountain on the refracted murder ballad “Wind Don’t Have to Worry”, haunted by backing vocalist Brandon Young’s androgynous soprano wail. “Baby’s Gonna Kick” stays low to the ground, set off by a smoldering Lancio solo, while Hiatt channels Howlin’ Wolf on “Nothin’ I Love”, whose dissolute narrator bemoans his weaknesses – “I drink too much, I take too many pills/Ain’t too long before my mind gets ill” – before delivering the album’s most resonant line: “Nothin’ I love is good for me but you”. “Old People” starts out with a jokiness redolent of Randy Newman but then takes on a certain gravitas – it seems the song’s road-hogging senior citizens are in a big hurry to slow down time. The existential poignancy in the title song is palpable, as Hiatt acknowledges his failures and regrets. “When the moon is rising/And the night is still”, he sings in a world-weary baritone, “Some of my delusions have the power to kill/Scared I’ll get what I deserve/Or maybe scared I won’t”. There’s a passage in “Long Time Comin’” that crystallizes the album and Hiatt’s latter-day body of work as a whole: “I’ve sang these songs a thousand times, ever since I was young/It’s a long time comin’ and the drummer keeps drummin’, your work is never done”. This is one old timer who’s still in his prime, doing his damnedest to keep it going till it’s all used up. Bud Scoppa Q&A John Hiatt To what do you attribute your longevity and your undiminished productivity? You hit a point where you start to feel that time’s running out and getting more precious, and I want to do the best work I can and as much as I can before I kick the bucket. That’s pretty much what it is. If you hang around and you don’t embarrass yourself, you’re in pretty good shape. You can even embarrass yourself, actually; I’ve done that. You’ve mixed things up from album to album in recent years, but there’s a consistent thematic thread running through all of them. It’s about the adventure, and the constant is me and what I do. It’s not the idea. Fuck the idea – I got a million of them. I like trying new things, and I like good music. I don’t have a notion other than let’s put some players together with somebody who knows their way around a studio and some arrangements, and we might make some great music. Your songs, and especially your love songs, are quite different from what a young man would write, and they seem as genuine as anything you’ve ever done. It’s the endurance of love, and also how broken it gets, and how broken we are – how broken I am, anyway – and how it just seems never-ending; the pieces breaking apart and being put back together somehow. INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA

The past, present and future intertwine on the veteran’s latest effort…

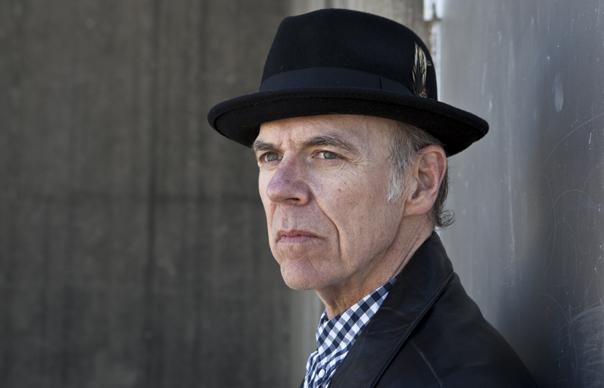

For writer/artists of a certain age, the sands of time can be like quicksand, sucking them under as they grasp at their past achievements. John Hiatt is one of the handful of exceptions to this entropic pattern; at age 61, he’s as prolific, expressive and energetic as ever, demonstrating that a gifted songwriter who’s dialed into the process of aging can continue to find fertile subject matter.

Hiatt hasn’t allowed himself to be trapped in the shadow of his 1987 classic Bring The Family, his inspired collaboration with Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe and Jim Keltner, which could’ve been the hellhound on his tail if he’d succumbed to an ever more desperate need to try and match it, like so many of his contemporaries; instead, he’s kept plugging away as an indie artist, taking life as it comes. His postmillennial output – nine albums in 14 years, each one of them with its own distinct character and brace of memorable songs – has actually outpaced his rate of productivity on several major labels in the first quarter century of his career.

Hiatt’s recent work has yielded some particularly impressive LPs. 2003’s Beneath This Gruff Exterior, produced by the late, great Don Smith (Petty, Wilburys) finds Louisiana slide wizard Sonny Landreth letting rip. Master Of Disaster (2005), had roots legend Jim Dickinson at the console and the North Mississippi All Stars, featuring Dickinson’s sons, providing the shit-kicking vibe. On 2008’s self-produced Same Old Man, a burnished, elegiac song cycle focused on the ups and downs of a long-term relationship, leading to some of the veteran artist’s most emotionally authentic performances.

Although Hiatt has been clean since 1985, leading a quiet life with his wife and kids outside of Nashville, recollections of his wild years have continued to provide him with grist for the songwriting mill. “Mistakes are to be highlighted,” he noted in 2008. “You can’t have the light without the dark.” That duality permeates the new Terms Of My Surrender. Its songs are blues-based reflections recalling the sauntering grooves of J.J. Cale, the gritty swamp rock of Tony Joe White and Bob Dylan’s Modern Times throughout. Hiatt keeps things close to the bone, using his touring band, with guitarist Doug Lancio doubling as producer, and basing the predominantly understated performances around his lived-in voice, acoustic guitar and harmonica.

In the middle of opening track “Long Time Comin’” Lancio unleashes thunderbolts with a powerfully evocative guitar solo that emphatically amplifies the intensity of the lyric, evoking Daniel Lanois’ atmospheric eruptions on Emmylou Harris’s Wrecking Ball. Hiatt goes down to the crossroads on the 12-bar blues “Face of God” and treks to Cold Mountain on the refracted murder ballad “Wind Don’t Have to Worry”, haunted by backing vocalist Brandon Young’s androgynous soprano wail. “Baby’s Gonna Kick” stays low to the ground, set off by a smoldering Lancio solo, while Hiatt channels Howlin’ Wolf on “Nothin’ I Love”, whose dissolute narrator bemoans his weaknesses – “I drink too much, I take too many pills/Ain’t too long before my mind gets ill” – before delivering the album’s most resonant line: “Nothin’ I love is good for me but you”.

“Old People” starts out with a jokiness redolent of Randy Newman but then takes on a certain gravitas – it seems the song’s road-hogging senior citizens are in a big hurry to slow down time. The existential poignancy in the title song is palpable, as Hiatt acknowledges his failures and regrets. “When the moon is rising/And the night is still”, he sings in a world-weary baritone, “Some of my delusions have the power to kill/Scared I’ll get what I deserve/Or maybe scared I won’t”.

There’s a passage in “Long Time Comin’” that crystallizes the album and Hiatt’s latter-day body of work as a whole: “I’ve sang these songs a thousand times, ever since I was young/It’s a long time comin’ and the drummer keeps drummin’, your work is never done”. This is one old timer who’s still in his prime, doing his damnedest to keep it going till it’s all used up.

Bud Scoppa

Q&A

John Hiatt

To what do you attribute your longevity and your undiminished productivity?

You hit a point where you start to feel that time’s running out and getting more precious, and I want to do the best work I can and as much as I can before I kick the bucket. That’s pretty much what it is. If you hang around and you don’t embarrass yourself, you’re in pretty good shape. You can even embarrass yourself, actually; I’ve done that.

You’ve mixed things up from album to album in recent years, but there’s a consistent thematic thread running through all of them.

It’s about the adventure, and the constant is me and what I do. It’s not the idea. Fuck the idea – I got a million of them. I like trying new things, and I like good music. I don’t have a notion other than let’s put some players together with somebody who knows their way around a studio and some arrangements, and we might make some great music.

Your songs, and especially your love songs, are quite different from what a young man would write, and they seem as genuine as anything you’ve ever done.

It’s the endurance of love, and also how broken it gets, and how broken we are – how broken I am, anyway – and how it just seems never-ending; the pieces breaking apart and being put back together somehow.

INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA