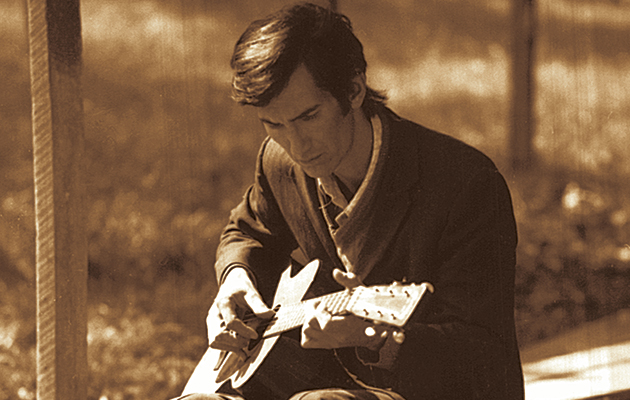

It could have been the record that made him; maybe, even the record that saved him. In 1972, the 28-year-old Texan prodigy Townes Van Zandt had released his sixth studio album in five productive years, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt. It was arguably his best album to that point, and certainly contained what would become Van Zandt’s best-known song – “Pancho & Lefty”, since duetted upon by Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson, and recorded or performed by Emmylou Harris, Hoyt Axton, Bob Dylan and Steve Earle, among uncountable others. Keen to keep up with songs pouring out of him, in early 1974 Van Zandt returned to the studio to begin work on his seventh album, surely the big breakthrough, to be entitled Seven Come Eleven.

Seven Come Eleven ended up being lost as collateral damage in a dispute between Van Zandt’s manager Kevin Eggers, and producer Cowboy Jack Clement. The label concerned, Poppy, went bust. Van Zandt wouldn’t release another album for five years – an interregnum substantially spent living in a tin shack outside Nashville with a teenage second wife named Cindy and a wolf-husky crossbreed called Geraldine, passing his days drinking, shooting narcotics and guns, and watching reruns of Happy Days. Six tracks originally cut for Seven Come Eleven would eventually be reworked for that long-delayed next album, 1978’s Flyin’ Shoes; others would surface on the later “Live At The Old Quarter” and “At My Window”. Seven Come Eleven itself would languish unheard for 20 years, until released as The Nashville Sessions in 1993, by which time Van Zandt had barely three years left to live.

This re-release of The Nashville Sessions heralds a welcome programme of reissues of Van Zandt’s recordings for Poppy, and its later reincarnation, Tomato. It includes a lavish sleeve featuring Milton Glaser’s original artwork, an illustrated twelve-page booklet, and splendid liner notes by Rob Hughes of this parish. It has also been remastered from the original tapes – work more urgent in the case of The Nashville Sessions than for most albums. According to persistent legend, the record only exists at all because Eggers, afeared that a vengeful Clement was about to erase the master tapes, crept into Jack’s Tracks Studios one night and transferred Van Zandt’s semi-complete work onto cassettes.

As such, no amount of buffing, polishing and scrubbing is ever going to make Seven Come Eleven sound like much beyond a bunch of half-baked demos – the sound overall is muddy and crackly, esses fizz against the microphone, a background tape hiss is perceptible throughout, and Van Zandt’s vocals, many of which are surely guide tracks, are far from his most adroit. But a forgiving listener can nevertheless still enjoy this raw, lo-fi work-in-progress as, say, Van Zandt’s “Nebraska”: certainly, the songs are good enough.

Some, indeed, rank high among his finest. The opening tune “At My Window”, later the title track of Van Zandt’s 1987 album, is an especially heartbreaking hint of what might have been, 14 years earlier – “Living is sighing,” croons Van Zandt, nailing one of his trademark nihilist aphorisms over a swell of sumptuous countrypolitan strings, “dying says nothing at all.” “No Place To Fall” waltzes between a knelling piano and a gently giddy accordion, Van Zandt pleading for pre-emptive forgiveness of the troubadour’s unreliability: “I ain’t much of a lover, it’s true/I’m here then I’m gone/And I’m forever blue”. “Loretta”, a few tracks later, sounds a sketch of the infinitely tolerant ideal imagined recipient of such an apology: “Oh, Loretta, won’t you say to me/Darling put your guitar on/Have a little shot of booze/Play a blue and wailing song”. Between the whisper of rueful self-mockery in his delivery, and the the upbeat zydeco swing of the melody, Van Zandt just about gets away with it.

Despite this, and the case made by bluegrass shuffle “White Freight Liner” and the closing gospel rave “Upon My Soul”, upbeat was never Van Zandt’s natural habitat. As a general rule, on The Nashville Sessions as throughout Van Zandt’s catalogue, the more wretched he sounds, the better – and on the best parts of “The Nashville Sessions” he almost makes melancholy sound a condition to be envied. “Two Girls”, a recognisable musical cousin to “Pancho & Lefty”, is a surreal, hungover delusion (“All Beaumont’s full of penguins/And I’m playing it by ear”), and “When She Don’t Need Me” says all Van Zandt ever had to say, pretty much: “Cling to the darkness/Until you’ve turned to song.”