Despite his claim that he considered himself part American since the first time he heard Elvis, in the final analysis America was not good for John Lennon. He may have left Britain seeking freedom from the small-mindedness and the racism directed at Yoko, but the impact on his creativity was just ca...

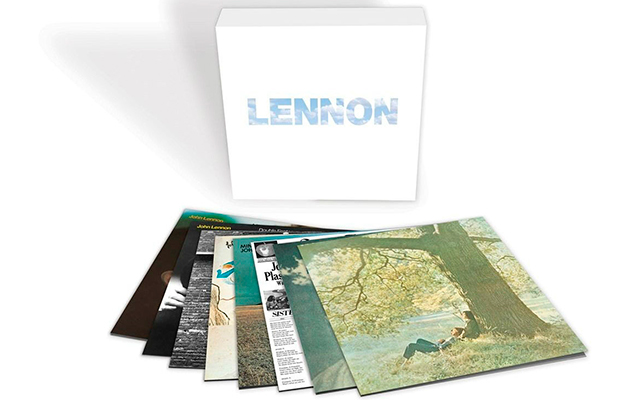

Despite his claim that he considered himself part American since the first time he heard Elvis, in the final analysis America was not good for John Lennon. He may have left Britain seeking freedom from the small-mindedness and the racism directed at Yoko, but the impact on his creativity was just catastrophic, as this boxset of vinyl reissues demonstrates in the contrast between the vicious purity of his solo debut, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, and the sweeter pop perfection of the follow-up Imagine, with anything that followed.

Influenced by undergoing Primal Scream Therapy, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band presents the singer peeled to his core, dredging up tormenting traumas – notably, parental abandonment – and dispelling them through cathartic bursts of honesty rarely heard in pop music. This confrontational approach involves Lennon being progressively scoured of illusions, notably in the angry “I Found Out” and bitter “Working Class Hero”, eventually culminating in “God”, a litany of iconoclastic demurral rejecting not just religion but all the bogus pillars supporting his previous worldview, leaving him utterly alone, save for a single buttress: “Just believe in me; Yoko and me”. It’s a brutally selfish album – the long-held first syllable of “Isolation” is what the project’s all about, ultimately – and it’s never an easy listen: the backings, with Lennon accompanied by just Ringo Starr and Klaus Voorman, are likewise pared-back to match the material, leaving just his voice, carefully treated by Phil Spector, to occupy the foreground.

By comparison, Imagine is a joyous reaffirmation of pop naivete, for all the hard-edged bitterness of “I Don’t Want To Be A Soldier” and “Gimme Some Truth”, and the wilful spite of the McCartney-baiting “How Do You Sleep”, all of which are more readily listenable than the previous album. There’s a delight and uplift about “Oh Yoko!” that’s utterly infectious, and even the emotional palsy of “Crippled Inside” is dealt with in jaunty, singalong style. The naive charm of “Imagine” has sustained better than most utopian anthems, but the clincher here is “Jealous Guy”, as sweet as anything Lennon wrote: the whistling is a masterstroke, at once vulnerable and apologetic, tender and unthreatening.

But then, it all starts to go pear-shaped, with the crude sloganeering and rabble-rousing of Some Time In New York City, where the couple’s wafer-thin insights on contemporary issues like feminism, black power and the Troubles are set to generic rock music with nothing remotely revolutionary about it – even the Zappa/Mothers contributions on the live tracks are limp by their standards. A year later, Mind Games was written and recorded just as John and Yoko were splitting, and Lennon was under constant FBI surveillance – though the stress doesn’t seem to have prompted any sharp response beyond a few anodyne apophthegms, patronising homilies and bland apologies. And tellingly, the mantra-like title-track, the clear standout here, dated from the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band era.

Things went from bad to worse with Walls And Bridges, which features the worst opening track on any ex-Beatle album (“Going Down On Love”) and a tranche of uninspired, self-pitying funk-soul cuts, the best of which – “Scared” and “Steel And Glass” – ape Bobby Bland’s contemporary R&B style. But perhaps the saddest aspect of the album is that Lennon needed a little of Elton John’s charisma to score the only Number One solo single of his lifetime with “Whatever Gets You Through The Night”, whose cheesy, sax-riffing effervescence hasn’t aged at all well.

The oldies album Rock’n’Roll was better, but still patchy. “Peggy Sue” sounds too thick, “Rip It Up/Ready Teddy” too thin, and the reggaefied “Do You Wanna Dance” is an abomination. But “Be-Bop-A-Lula” stalks along nicely, and “Stand By Me” shifts engagingly from folksy opening to soul climax. The album was partly legal payback for Lennon using a line from “You Can’t Catch Me” in “Come Together”, though rather than whisking lightly along like the Chuck Berry original, the version here is mired in lolloping boogie brass.

Following five years of house-husbandry raising his son Sean, Double Fantasy was better than expected, but still mediocre. The air of domestic tranquility, while rather irritating, was well conveyed in “Beautiful Boy” and “Woman”, the simplicity of the sentiment echoed in the melody and arrangement; but it was a patchy affair, despite the clear improvement in Yoko’s contributions. By the posthumous Milk And Honey, four years later, her tracks display a greater variety and charm than Lennon’s, which are sadly more meat and potatoes than milk and honey: to be generous, possibly demos denied their due development.

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.