There’s an instructive anecdote that Phil Collins has told about his 1970 audition to become drummer of Genesis, then a young band who had just completed their second album, Trespass. While aspirant percussionists auditioned in an outbuilding at Peter Gabriel’s parental home, the young hopeful relaxed in the swimming pool, taking in the unfamiliar grandeur of the surroundings. A peculiar feature of this was guitarist Mike Rutherford, who Collins observed striding over the lawn, apparently having just got out of bed. What marked the situation out as odd was when Collins realized Rutherford wasn’t staying in the house at all: he had driven 50 miles from his own home, dressed in pyjamas and a dressing gown. Partly theatrical, partly eccentric, very public school, it’s an image that’s worth bearing in mind when considering Genesis’s early works, collected here in a comprehensive box set. After 1975, Genesis journeyed gradually from slick prog, ultimately becoming what we know them as today: men in linen suits, playing slightly wry pop. For their first five albums, however, Genesis and their original singer Peter Gabriel were up to something unimaginably weirder. A curious blend of pantomime, progressive rock, and Brideshead Revisited, these former Charterhouse pupils presented a Mellotron-soaked vision based in fantasy and religion, and pricked, on occasion, by social conscience. It’s interesting to note, though, that while much of what this set contains is pretty forbidding to the listener – Genesis specialized then in allusive pieces at which even band members confess to occasionally now cringing – there is only one truly disingenuous-sounding moment in the set. It arrives courtesy of the last words sung on the band’s final album, and comes in the form of a quote from the Rolling Stones: “It’s only rock ‘n’roll…” Peter Gabriel sings on the final track, “It”. “But I like it….” A song about Victorian botany (“The Return Of The Giant Hogweed”). A 23 minute concept song about death and dying, (“Supper’s Ready”), which would be performed live with the lead singer dressed as a flower. A hit single sung from the point of view of a lawnmower. The records that Genesis made in the first part of the 1970s were many things, but simple rock ‘n’ roll was not one of them. The most successful parts of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway bear comparison to The Who’s Tommy, but really that was as far as Genesis seem to have wanted to go with rock ‘n’ roll. Instead, the story of this set (there is an interesting Extras disc, and pertinent DVD content accompanies each album) is of a break with rock ‘n’ roll tradition, if not as musically enduring, then certainly as purposeful as that made by Germany’s “Krautrock” musicians at about the same time. Before Trespass, Genesis had been a talented beat group, whose 1968 Jonathan King-produced single “Silent Sun” was a late-blooming fruit of British psych pop. The impetus for the band’s change into Darwinian rock band seems to have been the growing pains of another group. “I wanted to write something with the energy of “Rondo” by The Nice,” Peter Gabriel said of the band’s eureka moment. What he ended up writing was a ten minute piece (with pastoral flute midsection) called “The Knife”. A progressive rock milestone, “The Knife” very much drew out a map for the band’s subsequent explorations. A churning, Bach-like, keyboard-driven piece in which a nation is encouraged to throw off its oppressors, it’s not so much a song, as it is a dramatic recitation, and marks the point at which some good ideas seem to change, for Genesis, into some pretty inelastic principles, and ultimately harden into full-blown concepts. Throughout their next two albums, (1971’s Nursery Cryme and 1972’s more commercially successful Foxtrot) Genesis moved towards longer and longer songs, and further into suite-like constructions. 1971’s ten minute “The Musical Box” not only evokes the band’s customary mood of malevolent Victoriana, but seems to herald the hugeness of Foxtrot’s centerpiece, “Supper’s Ready”. These are on occasion musically striking songs, Peter Gabriel’s vocals bringing an unexpected soul into these macabre tales, the band a tight negotiator of labyrinthine paths, but the pieces that fail seem terribly unwieldy. With the music having grown larger in rehearsal improvisation, the themes of these songs have expanded to fit it, not always to their benefit. Some of them, (property development homily “Get ‘Em Out By Friday” or “The Battle Of Epping Forest” (from 1973’s Selling England By The Pound) today seem like curiosities from a different historical period, like a maze in a stately home. Once, people entered for pleasure. Now you simply get lost in them. The logical end of this growth and expansion was, inevitably, the double concept album. Evidently difficult to conceive of, 1974’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway effectively split the band – the frankly unfathomable story followed the fortunes of Rael, a Puerto Rican graffiti artist – but is nonetheless not without genuinely great moments. Soaked in American influence after touring throughout the United States, Lamb released Genesis from its English captivity, and set it in a wider context, in which the band undoubtedly prospered. “Fly On A Windshield”, in which the band conceived of themselves “as Pharoahs traveling down the Nile”, guitarist Steve Hackett and keyboard player Tony Banks engaged in an effort to out grandiose each other, is an undoubted highlight, while the album is rich in sexual innuendo, which is creepily successful at least as often as it is plain embarrassing. What becomes evident as the album moves forward into its second disc, however, is the sound of a band being imprisoned by the very format which they had entered, hoping for liberation. Their one unifying concept has become a burden too heavy to carry – and in spite of Genesis’s efforts, a thousand songs, and as many changes of time signature would never be enough to satisfactorily support it. So much so, that as the band enter the interminable peregrinations of the final song, “It”, you come to think when Peter Gabriel quotes the Stones, it’s less an ironic gesture, and more a plea for a certain kind of musical simplicity. Though they’d taken it a long way, what Genesis were up to was only rock ‘n’ roll, after all. Now, after a fashion, they had to find a way back to it. JOHN ROBINSON

There’s an instructive anecdote that Phil Collins has told about his 1970 audition to become drummer of Genesis, then a young band who had just completed their second album, Trespass. While aspirant percussionists auditioned in an outbuilding at Peter Gabriel’s parental home, the young hopeful relaxed in the swimming pool, taking in the unfamiliar grandeur of the surroundings. A peculiar feature of this was guitarist Mike Rutherford, who Collins observed striding over the lawn, apparently having just got out of bed. What marked the situation out as odd was when Collins realized Rutherford wasn’t staying in the house at all: he had driven 50 miles from his own home, dressed in pyjamas and a dressing gown.

Partly theatrical, partly eccentric, very public school, it’s an image that’s worth bearing in mind when considering Genesis’s early works, collected here in a comprehensive box set. After 1975, Genesis journeyed gradually from slick prog, ultimately becoming what we know them as today: men in linen suits, playing slightly wry pop. For their first five albums, however, Genesis and their original singer Peter Gabriel were up to something unimaginably weirder. A curious blend of pantomime, progressive rock, and Brideshead Revisited, these former Charterhouse pupils presented a Mellotron-soaked vision based in fantasy and religion, and pricked, on occasion, by social conscience.

It’s interesting to note, though, that while much of what this set contains is pretty forbidding to the listener – Genesis specialized then in allusive pieces at which even band members confess to occasionally now cringing – there is only one truly disingenuous-sounding moment in the set. It arrives courtesy of the last words sung on the band’s final album, and comes in the form of a quote from the Rolling Stones: “It’s only rock ‘n’roll…” Peter Gabriel sings on the final track, “It”. “But I like it….”

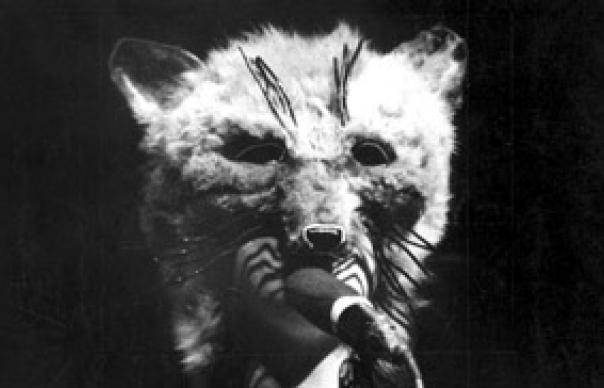

A song about Victorian botany (“The Return Of The Giant Hogweed”). A 23 minute concept song about death and dying, (“Supper’s Ready”), which would be performed live with the lead singer dressed as a flower. A hit single sung from the point of view of a lawnmower. The records that Genesis made in the first part of the 1970s were many things, but simple rock ‘n’ roll was not one of them. The most successful parts of The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway bear comparison to The Who’s Tommy, but really that was as far as Genesis seem to have wanted to go with rock ‘n’ roll.

Instead, the story of this set (there is an interesting Extras disc, and pertinent DVD content accompanies each album) is of a break with rock ‘n’ roll tradition, if not as musically enduring, then certainly as purposeful as that made by Germany’s “Krautrock” musicians at about the same time. Before Trespass, Genesis had been a talented beat group, whose 1968 Jonathan King-produced single “Silent Sun” was a late-blooming fruit of British psych pop. The impetus for the band’s change into Darwinian rock band seems to have been the growing pains of another group. “I wanted to write something with the energy of “Rondo” by The Nice,” Peter Gabriel said of the band’s eureka moment. What he ended up writing was a ten minute piece (with pastoral flute midsection) called “The Knife”.

A progressive rock milestone, “The Knife” very much drew out a map for the band’s subsequent explorations. A churning, Bach-like, keyboard-driven piece in which a nation is encouraged to throw off its oppressors, it’s not so much a song, as it is a dramatic recitation, and marks the point at which some good ideas seem to change, for Genesis, into some pretty inelastic principles, and ultimately harden into full-blown concepts.

Throughout their next two albums, (1971’s Nursery Cryme and 1972’s more commercially successful Foxtrot) Genesis moved towards longer and longer songs, and further into suite-like constructions. 1971’s ten minute “The Musical Box” not only evokes the band’s customary mood of malevolent Victoriana, but seems to herald the hugeness of Foxtrot’s centerpiece, “Supper’s Ready”. These are on occasion musically striking songs, Peter Gabriel’s vocals bringing an unexpected soul into these macabre tales, the band a tight negotiator of labyrinthine paths, but the pieces that fail seem terribly unwieldy. With the music having grown larger in rehearsal improvisation, the themes of these songs have expanded to fit it, not always to their benefit.

Some of them, (property development homily “Get ‘Em Out By Friday” or “The Battle Of Epping Forest” (from 1973’s Selling England By The Pound) today seem like curiosities from a different historical period, like a maze in a stately home. Once, people entered for pleasure. Now you simply get lost in them.

The logical end of this growth and expansion was, inevitably, the double concept album. Evidently difficult to conceive of, 1974’s The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway effectively split the band – the frankly unfathomable story followed the fortunes of Rael, a Puerto Rican graffiti artist – but is nonetheless not without genuinely great moments. Soaked in American influence after touring throughout the United States, Lamb released Genesis from its English captivity, and set it in a wider context, in which the band undoubtedly prospered. “Fly On A Windshield”, in which the band conceived of themselves “as Pharoahs traveling down the Nile”, guitarist Steve Hackett and keyboard player Tony Banks engaged in an effort to out grandiose each other, is an undoubted highlight, while the album is rich in sexual innuendo, which is creepily successful at least as often as it is plain embarrassing.

What becomes evident as the album moves forward into its second disc, however, is the sound of a band being imprisoned by the very format which they had entered, hoping for liberation. Their one unifying concept has become a burden too heavy to carry – and in spite of Genesis’s efforts, a thousand songs, and as many changes of time signature would never be enough to satisfactorily support it.

So much so, that as the band enter the interminable peregrinations of the final song, “It”, you come to think when Peter Gabriel quotes the Stones, it’s less an ironic gesture, and more a plea for a certain kind of musical simplicity. Though they’d taken it a long way, what Genesis were up to was only rock ‘n’ roll, after all. Now, after a fashion, they had to find a way back to it.

JOHN ROBINSON