“If I ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dreams…” It’s one of the most enigmatic, evocative opening lines in all of pop history, akin to Alice’s dive down the rabbit-hole in the way it serves as an indication of the enchantments to come. Possibly the most sui generis ...

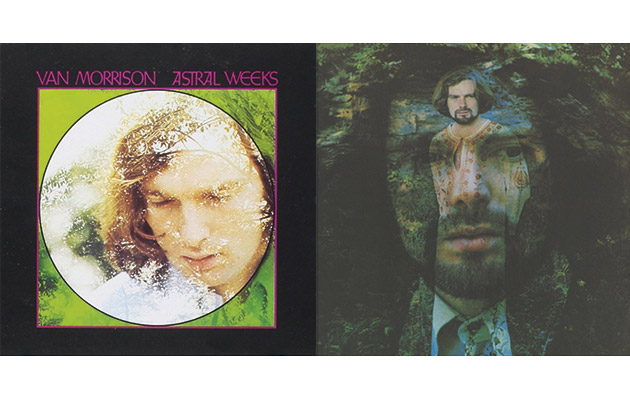

“If I ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dreams…” It’s one of the most enigmatic, evocative opening lines in all of pop history, akin to Alice’s dive down the rabbit-hole in the way it serves as an indication of the enchantments to come. Possibly the most sui generis album ever created, Astral Weeks, no matter how many times you’ve listened to it, somehow weaves its magic anew each time you return.

The LP’s roots lay in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Morrison and his wife, Janet “Planet” Rigsbee, were living in 1968, hiding out from mob associates of the late producer/songwriter/label boss Bert Berns, who still held his contract (subsequently bought out by Warner Brothers’ Joe Smith, who reportedly delivered $20,000 to mobsters in an abandoned warehouse). Frustrated at the tight, claustrophobic arrangements Berns had insisted on employing, Morrison was experimenting with just acoustic guitars, string bass and flute, and when it came time to record his new, expansive songs, producer Lewis Merenstein assembled a team of simpático jazz players more used to working with the likes of Eric Dolphy and Charles Mingus.

Recorded in New York’s Century Sound Studios, the songs were borne along on the most flexible of jazz accompaniments – magically improvised, in some cases on the first take, by musicians who hadn’t even had lead sheets or rehearsals – with haunting string arrangements overdubbed later. Low shivers of strings, glistening highlights of vibes, and feathery flutters of flute are lightly held together by rhythm guitar and double bass, while Morrison’s scorched soul phrasing sketches a mystic yearning “to be born again… in another world, in another time”. It’s a series of spellbinding performances, poised between emotion and imagination, memory and visualisation, past and future, with the woodwind and strings seeming to caress the soulful delivery from Morrison’s very spirit.

Throughout the album, reveries of teenage romance and reminiscences of his Belfast youth mingle with fantasy visions and expressions of a desire for spiritual rebirth, for “transforming energy”, as he explained it. In “Cyprus Avenue”, courtly harpsichord and rhapsodic violin follow Morrison as he gazes from a car at a young girl, imagining her as a refined maiden from a historical tableau, riding in a horse-drawn carriage; while the album centrepiece, “Madame George”, offers an impressionistic portrait of bohemian Belfast, with the titular drag queen stirring confused feelings in adolescent boys. The conclusion, with Morrison’s wistful humming echoed by the yearning strings as he waves “goodbye, goodbye, goodbye”, is endlessly, eternally moving.

“Madame George” is one of four tracks also included as outtakes in this expanded edition. Shorn of its string overdubs, and with the flute dropping out around three minutes in, it’s virtually just Van’s acoustic strumming and Richard Davis’ yawning bass accompanying his vocal, with sparse vibes quietly underscoring the chords. The lack of strings does leach the song of some of its wistful sadness – in particular, the line “when you fall into a trance” doesn’t soar so euphorically – and it seems to limp to an ending rather than surge towards it, Morrison concluding with a whisper, followed by the businesslike announcement for the next take.

Despite some nice interplay between guitar and vibes, an additional long version of “Ballerina” is spoilt by Morrison’s rhythm guitar being higher in the mix, his occasional double-time flourishes blurring the delicate momentum, and by the more obtrusive entry of the burring horns three minutes in. There’s also an uncut version of “Slim Slow Slider”, the haunting song about a dying girl (echoing Morrison’s earlier “TB Sheets”) that closes the album. Played largely as a two-hander between Van’s vocal and John Payne’s soprano saxophone, it retains its enigmatic, troubling mood, but is then elongated with a further couple of minutes of sax improvisation, until Morrison draws it to a close by sombrely intoning “Glory be to Him” several times.

The other bonus cut, the first take of “Beside You”, is perhaps the most revealing. It’s the earliest of the songs to be written, having originally been rehearsed with Them in 1966, and Morrison seems more comfortable with it: there’s a smoother flow than the take eventually used on the album, but the delicate waltz between his and John Platania’s guitars hasn’t yet developed some of the latter’s more affecting responses, like the figure answering the reference to “backstreets”; and the “breathe in, you breathe out” section is far less urgent. But what surprises is just how precisely Morrison has designed these songs, which, thanks to the arrangements, seem more improvised and free-form in structure. Certainly, through all the outtakes, his own delivery rarely wavers from the album versions, only “Madame George” accruing a more satisfying extemporised conclusion.

Also reissued here is an expanded edition of His Band And The Street Choir, often downgraded largely due to its being just brilliant rather than perfect, like its two immediate predecessors. Heard again after a long hiatus, it’s a wonderful resolution of the lighter R’n’B elements of Moondance, with barely a misstep – although the worldly, less mystical nature of the material leaves it more enjoyable, rather than magical. Which isn’t to say that it doesn’t have myriad extraordinary moments, like the sprightly “Domino” (still Van’s biggest US hit), and the mysterious, Band-like “Crazy Face” with its outlaw mystique and bizarre, trilled sax solo.

Of the additional outtakes, the third take of “Give Me A Kiss” finds the song closing in on its graceful, limber swing, while an alternative version of “I’ll Be Your Lover, Too” seems more hesitant, lacking the focused quiet passion of the album version. Most entertaining are the first takes of “Gypsy Queen”, with Van responding to a fluffed intro with a genial, “Yer man… he’s up in the spacecraft or something, floating around up there”, before blowing the next intro himself.

The spartan funk groove of “I’ve Been Working”, though, provides the most thrilling of the five additional outtakes, given a faster, simplified stomp arrangement that starts like a James Brown workout and thrillingly develops the muscular momentum of a lost Northern Soul classic, complete with fine sax and trumpet solos.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.