For a while in the mid-1990s, the West Midlands were home to a music festival called Phoenix; a slightly half-cocked Glastonbury surrogate that, far from taking place in idyllic Avalon, was established on a disused airfield-cum-landfill site blessed with little in the way of either shelter or shade....

For a while in the mid-1990s, the West Midlands were home to a music festival called Phoenix; a slightly half-cocked Glastonbury surrogate that, far from taking place in idyllic Avalon, was established on a disused airfield-cum-landfill site blessed with little in the way of either shelter or shade. Bob Dylan, possibly disoriented, would fill in a gap in the schedule between Suede and Tricky. Crazy Horse would face off against The Wedding Present. Hotels in nearby Stratford-Upon-Avon seemed perpetually haunted by the forlorn figure of Keith from The Prodigy, found wandering their corridors in the later early hours. It was all, I guess, very much of its time.

In that spirit, one year in the middle of the decade, the festival witnessed a clandestine special show. I can’t pretend to have seen it myself; I was languishing backstage, some way after midnight, when a friend returned from the dance tent in a state of some excitement. There, he had witnessed a deeply experimental, semi-improvised drum’n’bass set by a band billed as the Tao Jones Index. Their frontman, a notable lyrical collagist, appeared to be making up a lot of the words as he went along. Frequently, he would intone, with quasi-operatic portent, a newish buzzword of the time: “<>The Internet!<>”

This, I realise, is not how most people would likely remember David Bowie. But it strikes me today, in the wake of yesterday’s terrible news, that it’s a valuable way of understanding the nature of this most fearless of musicians. Many tributes in the past 24 hours have presented Bowie as a man of impeccable taste, as an artist whose every creative whim produced a cultural revolution.

And yes, of course, Bowie’s hit rate of innovation is probably higher than any other performer, never mind ones who operated for such a sustained length of time at such an exalted commercial level. But one of the keys to his genius, as the Tao Jones Index business illustrated so well, was that he was spectacularly unafraid of failing. The danger of looking daft was not something which seemed to bother Bowie unduly: for a man habitually associated with an elevated concept of cool, he was rarely afraid to place that coolness in jeopardy. In fact, the one time he seemed to try and insulate himself from potential embarrassment, he ended up in Tin Machine.

Risk was critical to the whole Bowie endeavour, a sense that preposterous ideas – ideas which could fall flat, could potentially end in humiliation – could just as easily turn out to reconfigure our ideas of what a pop star could be, what pop could do. As we sit hear and try to come to terms with the loss, and at the same time attempt to measure out the mind-boggling scope and impact of his career, I think it’s useful to see Bowie’s journey as a long-distance highwire walk. A mutant-jazz album as valediction? How on earth would that work?

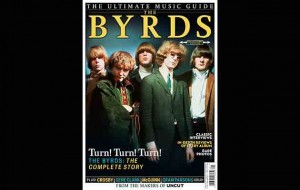

Anyhow, we’re currently working, as you might imagine, on a special edition of Uncut. In the meantime, you can still pick up a copy of our Ultimate Music Guide to Bowie, and we have a further Ultimate Music Guide going on sale this week – this one dedicated to The Byrds, and the subsequent illustrious solo careers of their various members. That goes on sale in the UK now, and you can pick up a copy of our Byrds Ultimate Music Guide from our online shop.