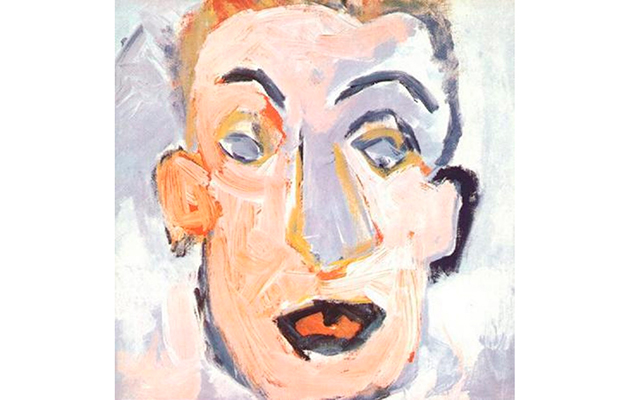

Continuing our celebrations of Bob Dylan's 80th birthday, this archive feature from Uncut's September 2013 issue, burrows into the sessions Dylan's Self Portrait album - which had just been re-issued in expanded form as the Bootleg Series Volume 10: Another Self Portrait. Here, Damien Love spoke to ...

Continuing our celebrations of Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday, this archive feature from Uncut’s September 2013 issue, burrows into the sessions Dylan’s Self Portrait album – which had just been re-issued in expanded form as the Bootleg Series Volume 10: Another Self Portrait. Here, Damien Love spoke to three key players on the Self Portrait sessions and find out details of the Bootleg Series team’s “deepest ever archaeological dig”…

Charlie McCoy

The Nashville studio multi-instrumentalist who played on every Dylan album from Highway 61 Revisited to Self Portrait

When Dylan first showed up in Nashville to record Blonde On Blonde, he hadn’t finished writing the first song. We ended up recording it at 4 o’clock in the morning. And we’d all been there since 2PM the afternoon before. Dylan’s flight was late, and when he arrived he hadn’t wrote the first song he wanted to do. He said, “You guys just hang loose till I finish it.” So we sat around while he wrote “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”.

- ORDER NOW: The Complete Bob Dylan – a meticulous, left-field guide to Bob’s outstanding output since 1962

Dylan seemed a little uncomfortable in Nashville at first, because he was in a strange place, with strange musicians, although he had Al Kooper and Robbie Robertson on board with him. But he never said anything to us really, so it was hard to tell just what he was thinking or feeling. But, the next day, we came back to the studio, and from there it was pretty much business as usual then: I mean, he still didn’t say too much, but he started playing his songs, and we started recording them.

But, like I said, he never said anything. I was session leader on that record, and when you’re session leader, you’re like the middleman between the artist and the producer. So, Dylan would pick up his guitar and play his song to us, and I’d hear it, and I’d immediately start to get some ideas, and I’d say, “Bob, what would you think if we did this, or that…” And he’d have the same answer every time: “I dunno, man. Whadda you think?” He was very strange in that way, very hard to read.

When we did John Wesley Harding, I didn’t have any information prior to going in about what it was going to be like. But Nashville studio musicians, we go to work every day, usually never knowing what we’re going to be doing. We hear the music the first time we walk into the studio. We’re used to that, it’s just the normal way it’s done here.

I noticed that there was a definite shift in the music, though, the style. After Blonde On Blonde, Dylan had that motorcycle wreck. I don’t know if that has anything to do with anything. But I know that that was a major happening to him in his life, one that had nothing to do with music. Blonde On Blonde took 39-and-a-half hours of studio time to record. John Wesley Harding took nine-and-a-half hours. Of course, the band was much, much smaller. Just Dylan, me on bass, and Kenny Buttery on drums. There was steel guitar on a couple tracks, too, but that was it – there wasn’t much on that record. But as for Dylan himself, there was no change. The same thing: he’d play a song and not say anything.

The next time round was Nashville Skyline, which again was a shift, a step into country. John Wesley Harding, especially those last two tracks, seemed a kind of a bridge towards that sound, and Dylan had formed a friendship with Johnny Cash, so it didn’t really surprise me at all. I think Dylan hesitated about coming to Nashville originally, because it has always been known as the capital of country music. But we were known as a country market, and this was the height of what, in Nashville, we called The Hippy Period: that San Francisco, Haight-Ashbury, whatever it was scene. And, of course, Dylan, 1966, was seen as the champion of that group of people, he was the king of it.

He took a bold step by coming here. But Nashville Skyline was the last time he came to Nashville to record. Self Portrait, he wasn’t around. On some of the songs for that, Bob Johnston just brought us in recordings of Dylan, just guitar and vocal, and he asked Kenny and me to overdub bass and drums. And that was difficult, because Dylan’s tempos on those tapes really weren’t so steady. It was tough. But we added bass and drums to several songs. Why the record was done that way, I don’t know for certain. I’d have to say, though, that Self Portrait, it’s just not as vivid in my memory as the sessions when Dylan was there. I can remember songs from the first three records I worked on with him, but at this point, I couldn’t name you one single song from Self Portrait. I guess on this new version that’s coming out, if they’ve stripped all that stuff away, you’re going to be hearing the same tapes much as Kenny and I heard them, which could be interesting.

David Bromberg

Virtuoso guitarist and multi-instrumentalist who studied his craft with the Rev. Gary Davis, Bromberg was a key figure in the Self Portrait sessions and New Morning

The Self Portrait sessions were the first time I played with Dylan. At first, when I got a phone call from him – he called me himself – I thought it was a joke, somebody playing a trick. But I realised fairly swiftly that it actually was Bob Dylan on the phone. He’d come to various clubs in the Village where I was playing guitar for Jerry Jeff Walker, and I’d always assumed he was only there to hear Jerry Jeff. But I guess he was listening to me, too.

The way he put it to me was that he wanted me to help him “try out a studio.” It became clear to me pretty quickly that we weren’t just trying out a studio – we were recording. But I was too much in the moment to worry about what was going to happen in the future. So “trying out the studio” turned out to be making Self Portrait and then New Morning.

Most of what I remember is that it was just Bob and me in there. For several days straight, maybe even a couple of weeks, just the two of us, sitting across from each other playing and trying things. I had some really nasty cold thing going on all through that – I had a fever, and I’d work all day, come home and fall asleep in my clothes, wake up, take a shower and then head back into the studio and do it all over again. The songs that I did with him, as much as I can recall, were mostly folk songs. I’m not sure I remember seeing any Sing Out magazines, but Sing Out published a couple of songbooks, and I remember that Bob had one or two of those. But he knew those songs. He might have referred to the Sing Out books just to get a lyric here and there, but he knew those songs. Bob, as we all know, came up through the folk clubs, and he was really great at singing this music.

There was not a whole lot of discussion or direction. I think he liked how I played, and wanted to see what I’d come up with. Then he listened to the results, and what he really liked he used, and what he didn’t, he saved.

New Morning was quite different. There were quite a few musicians in the studio, a whole group. Russ Kunkel was on that, playing drums, and playing with him was a big thing for me, because I was always a huge fan of the way he plays. Of course, Bob doesn’t pick any losers. Ron Cornelius, was there, a fine guitar player. Ron played electric on that record, and I played acoustic and dobro.

In 1992, I produced another set of sessions with Bob in Chicago, and the great majority of those songs haven’t been heard yet, although a couple turned up on the Bootleg Series record Tell Tale Signs. On those sessions, I would have loved to have done some tunes that Bob wrote – but he didn’t want to do those. And, in fact, he did a few tunes that I had written. In a strange way, I was almost relieved that they didn’t come out, because people would have accused me of forcing Bob to do my songs. But let me just tell you: you don’t force Bob to do anything.

Recording sessions are all different. Bob has his own way of doing things, and it’s one that requires the musicians to be intuitive. And, in a musical sense, that’s one of my strengths. In a more prosaic sense, it’s one of my weaknesses: you know, if we’re going to do something, and I’m not told what we’re doing, I generally won’t figure it out. But when it comes to music, even if I haven’t been told where we’re going, I will figure it out. I’ll see ahead. And that’s kind of what’s required on Bob’s sessions. Perhaps the most important aspect of the process with Bob is that, Bob is very careful not to exhaust the material. And, as a result, there’s a spontaneity that’s present in all of his work. You’ll do a song once or twice, and that’s it: you’ve either got it or you don’t.

Al Kooper

Along with David Bromberg, one of Dylan’s favourite sidemen

I’d played on Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, but I’d left while Bob was doing John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline .Then I came back for what became Self Portrait.

From 1968 to 1972, I was a staff producer at Columbia Records in New York, so I was easy to contact. They just booked me for, I think it was five days of recording with Bob, like a Monday-Friday. There was Bob, David Bromberg and me. In some cases it was just the three of us, in others there was drums and bass in with us. It gets a little mixed up in my memory, because New Mornin happened very, very soon after Self Portrait, and I worked very closely on that album, probably as much as I had worked on Blonde On Blonde.

I remember us doing a lot of stuff that didn’t end up on Self Portrait. The first day I walked in to the studio, Bob had like a *pile* of Sing Out magazines, you know the folk music journal, just a bunch of them, and he was going through them, songs that he’d known in the past, and he was using the magazine to remind himself of them. So we were doing stuff pulled from Sing Out magazine, at least for a couple of days: “Days Of 49”, that kind of thing. As the week went on, Bob’s choices got stranger and stranger. It got to the point where we did “Come A Little Closer” by Jay And The Americans.

When we did New Morning, though, he was doing his songs again. And he had a definite, stronger thing going on. You know: he didn’t have to learn the songs, he wrote them. New Morning was very similar to Blonde On Blonde, in some ways, with the way I worked with Bob and acted as bandleader – and then, in the middle of the record, Bob Johnston just disappeared, and so for the second half of the record, I was actually producing it. I also had some arrangement ideas. Not that Bob always agreed with them. On the song “New Morning” itself, I did an arrangement where I put a horn section on there, and in “Sign On The Window,” I added strings, a piccolo, and a harp. I asked Bob’s permission, and he said fine, and then I went and did it all while he wasn’t there, because it didn’t need to take up his time. But when I played them back for him, he didn’t like them – he didn’t throw the whole thing out, he kept like one little part of each of them on the record. But then he told me he was going to erase all the rest of these parts, wipe the tapes. I asked if I could make a mix of it before he did that, because I had done a lot of work on it, and I wanted to keep a copy of it, just for myself. So he said yeah, but the way it worked, I had to mix it right there and then, in front of everybody, and do it fast.

On this new record that’s coming out now, they’ve included those sweetened versions of “New Morning” and “Sign In The Window”. I had kept my tapes of those personal mixes for like 40 years, and when I heard about this new set, I sent them to Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s manager, and Jeff said, “Well, I don’t like the mix.” And I said, “Yeah, it was a rush, but it’s all there is, because Bob erased all the parts afterwards.” And Jeff said, “No he didn’t. All the parts are still here. Do you want to remix it properly?” So that was great news to hear, and I went and did that. I spent quite some time doing that, and those are now on the new set.

Steve Berkowitz

A Bootleg Series veteran, on the restoration of the Isle Of Wight concert tapes

With the new version we’ve done of the Isle Of Wight concert, the first thing you have to remember is the circumstances of the original recording. It’s 1969. There are no cell phones. Basically, you’ve got a couple of guys stuck in a truck, hundreds of yards away from the stage. It had to have been madness. They’ve been awake for three days straight, and they’re recoding with no tangible connection to the stage or the board or what’s going on. You know: how many people are playing, where are the microphones, who else is set up at the same time, what time do they play, how long do they play for, are they gonna move around, when’s the guitar solo coming…? It’s a true testament to Glyn Johns and Elliott Mazer who did the original recording that they got it at all.

Their tapes have all the information on there, albeit kind of distorted, and sometimes without a direct microphone on anything, and with tremendous leakage from microphone to microphone. But the tapes themselves were in good shape, eight channels. So, in the new mix, we’ve tried to bring back in something of the size and scope of what was happening. For one reason or another, any time I’ve heard material from this concert in the past, the mix sounded small, close together, almost like a form of Basement Tapes, as if they were closed in together in a small space. But this was a huge open-air event, with tremendous anticipation, and, even at the time, some historic notoriety, because this was Dylan returning to the stage after three years away.

So we’ve tried to bring that back – make it live, make it as big as it was again, and have it feel like it’s out there, in this place, in the middle of hundreds of thousands of people, with excitement and energy bristling, both on stage and in the audience. The tapes are still kind of distorted in parts – but that’s okay. When you hear it now, it brings back the excitement and the tension of that moment. You know: Bob and The Band are playing, and they’ve got The Beatles sitting right there in front of them.

A personal favourite moment is the version they do of “Highway 61”. It sounds pretty clear that there are only overhead microphones over Levon Helm. And Levon sounds like he’s having a pretty good time: he’s hollering along with Bob, and you can really hear him – and I don’t think he even had a vocal mic at that time. I think it’s just these overheads are picking him up, because he’s singing it, screaming out so loud. It has fantastic life to it. And any distortion or bleeding makes no difference, because those guys are just rocking. It’s thrilling.

I should add that we’ve mixed everything both completely analogue and digital, and, for the people who care, I think the vinyl LP’s that come from this will be pretty great. They’re made like records were made, from tape and analogue mixes. We wanted to be faithful to the period – 1969-71 – and we thought that the record should sound and feel and be of the dimension of its time. They’re pretty special.

Our Ultimate Music Guide dedicated to Bob Dylan is available to buy from Amazon.