When John Densmore of The Doors first saw Arthur Lee's Love perform at Bido Lito's club in Hollywood in 1965, he knew he was witnessing something revolutionary. "They were deafeningly loud and they were mixed racially," Densmore tells the makers of Love Story. "My mind was blown, to use a '60s term... Here we've got a psychedelic black man." Love - with their three-guitar frontline of two Memphis-born blacks and a white Brian Jones lookalike - did a lot more than combine volume, visual impact and psychedelia. By their second and third albums (Da Capo and Forever Changes) they'd travelled so many dimensions from the garage-punk juvenescence of their debut LP that they effectively invented a new form of pop. Bacharach, Brasil '66 and Alpert (and, sublimely, the classical guitars of Rodrigo) were discombobulated into a schizophrenic imbalance of easy-listening euphoria and blood-in-the-bath-taps paranoia. In this universe, where the sun is not on its axis, premonitions of death in Vietnam are crooned prettily by men with peach Melba voices. Love Story, a 109-minute documentary shot by British filmmakers Chris Hall and Mike Kerry, argues that Love should have (and, if promoted more aggressively, could have) been a household name - which is debatable. They became a sleeper hit instead, destined to disintegrate, but never to be forgotten. Forever Changes may have hobbled into the Billboard chart at a lowly 154 (as an effective, slow-moving rostrum camera reveals), but it has since climbed 153 places in a few surveys listing the Greatest Albums Ever Made. Today its appeal is limitless and surprising; among the fans in Hall and Kerry's film is Ken Livingstone, no less, for whom Forever Changes was "the nearest that anything musical has come to changing my life". Using both new and archive footage, Love Story, which premiered at the London Film Festival two years ago, relies heavily on interviews with Arthur Lee (some of his last before his death from leukaemia in 2006) and Love's lead guitarist Johnny Echols. The latter is straight-talking, moderately bitter, easy to relate to. Lee, by contrast, wearing a series of implausible wigs and hats, speaks in slow, mumbled riddles. Sometimes he's funny, sometimes angry (notably on the race issue), sometimes too indistinct to comprehend. It's an odd criticism, but a fair one, that the undisputed leader of Love is overused in the documentary. A dull sequence early on, in which Lee drives around LA, must have been fun for his passenger but is sluggish for the viewer. Moreover, when Lee escorts us around the castle that was Love's communal home, we just know we're going to be shown every single room. Better use is made of Elektra boss Jac Holzman, wonderfully dry, and the fabled Alban 'Snoopy' Pfisterer, the original Love's somewhat hapless, Swiss-born drummer-turned-harpsichordist. Pfisterer, whom Hall and Kerry portray as a fitness-obsessed backwoodsman, seems a lovely chap. He and the aforementioned Holzman feature in an impressive sequence when Love, super-inspired, record "7 And 7 Is" (a 1966 single) and the planet appears to explode in astonishment. The ensuing Da Capo album, which has tended over the years to be overshadowed by Forever Changes, is given a pleasing amount of recognition. When "Orange Skies" is accompanied by some film of an orange-streaked sky, it's corny, it's literal and it's beautiful. A wholly successful effect. Forever Changes is handled as one would handle a priceless, delicate, easily chipped work-of-art. The masterpiece that broke the band up, it led to serious drug problems among the already divided personnel (although nobody goes into much detail), and its aftermath broke Lee's spirit. The musicians in his next line-up of Love hated Forever Changes and Lee was forced to laugh along with their mockery. I'd have liked more on this - and on the 30 years of Lee's life that followed - but Love Story discreetly lowers the curtain in 1968. A postscript jerks us forward to 2003 when Lee, not long released from prison where he has served five years for a firearms offence, goes on tour performing Forever Changes (something he refused to do at the time) and is cheered by full houses, new and old fans, rapturous disciples, Primal Scream members, newt-fancying Mayors of London, and all walks of life besides. DAVID CAVANAGH

When John Densmore of The Doors first saw Arthur Lee’s Love perform at Bido Lito’s club in Hollywood in 1965, he knew he was witnessing something revolutionary.

“They were deafeningly loud and they were mixed racially,” Densmore tells the makers of Love Story. “My mind was blown, to use a ’60s term… Here we’ve got a psychedelic black man.”

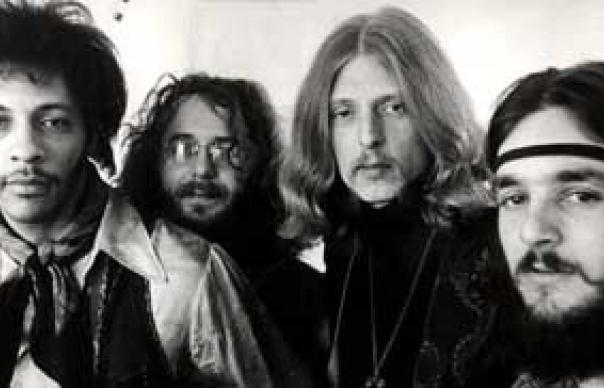

Love – with their three-guitar frontline of two Memphis-born blacks and a white Brian Jones lookalike – did a lot more than combine volume, visual impact and psychedelia. By their second and third albums (Da Capo and Forever Changes) they’d travelled so many dimensions from the garage-punk juvenescence of their debut LP that they effectively invented a new form of pop.

Bacharach, Brasil ’66 and Alpert (and, sublimely, the classical guitars of Rodrigo) were discombobulated into a schizophrenic imbalance of easy-listening euphoria and blood-in-the-bath-taps paranoia. In this universe, where the sun is not on its axis, premonitions of death in Vietnam are crooned prettily by men with peach Melba voices.

Love Story, a 109-minute documentary shot by British filmmakers Chris Hall and Mike Kerry, argues that Love should have (and, if promoted more aggressively, could have) been a household name – which is debatable.

They became a sleeper hit instead, destined to disintegrate, but never to be forgotten. Forever Changes may have hobbled into the Billboard chart at a lowly 154 (as an effective, slow-moving rostrum camera reveals), but it has since climbed 153 places in a few surveys listing the Greatest Albums Ever Made. Today its appeal is limitless and surprising; among the fans in Hall and Kerry’s film is Ken Livingstone, no less, for whom Forever Changes was “the nearest that anything musical has come to changing my life”.

Using both new and archive footage, Love Story, which premiered at the London Film Festival two years ago, relies heavily on interviews with Arthur Lee (some of his last before his death from leukaemia in 2006) and Love’s lead guitarist Johnny Echols. The latter is straight-talking, moderately bitter, easy to relate to. Lee, by contrast, wearing a series of implausible wigs and hats, speaks in slow, mumbled riddles. Sometimes he’s funny, sometimes angry (notably on the race issue), sometimes too indistinct to comprehend. It’s an odd criticism, but a fair one, that the undisputed leader of Love is overused in the documentary. A dull sequence early on, in which Lee drives around LA, must have been fun for his passenger but is sluggish for the viewer. Moreover, when Lee escorts us around the castle that was Love’s communal home, we just know we’re going to be shown every single room.

Better use is made of Elektra boss Jac Holzman, wonderfully dry, and the fabled Alban ‘Snoopy’ Pfisterer, the original Love’s somewhat hapless, Swiss-born drummer-turned-harpsichordist. Pfisterer, whom Hall and Kerry portray as a fitness-obsessed backwoodsman, seems a lovely chap. He and the aforementioned Holzman feature in an impressive sequence when Love, super-inspired, record “7 And 7 Is” (a 1966 single) and the planet appears to explode in astonishment.

The ensuing Da Capo album, which has tended over the years to be overshadowed by Forever Changes, is given a pleasing amount of recognition. When “Orange Skies” is accompanied by some film of an orange-streaked sky, it’s corny, it’s literal and it’s beautiful. A wholly successful effect.

Forever Changes is handled as one would handle a priceless, delicate, easily chipped work-of-art. The masterpiece that broke the band up, it led to serious drug problems among the already divided personnel (although nobody goes into much detail), and its aftermath broke Lee’s spirit. The musicians in his next line-up of Love hated Forever Changes and Lee was forced to laugh along with their mockery. I’d have liked more on this – and on the 30 years of Lee’s life that followed – but Love Story discreetly lowers the curtain in 1968.

A postscript jerks us forward to 2003 when Lee, not long released from prison where he has served five years for a firearms offence, goes on tour performing Forever Changes (something he refused to do at the time) and is cheered by full houses, new and old fans, rapturous disciples, Primal Scream members, newt-fancying Mayors of London, and all walks of life besides.

DAVID CAVANAGH