The sad story of Roland S Howard, vividly told... Romantic and beautiful, sad and funny, very cool and just a little bit pretentious – you’d have to say that Autoluminescent gets the flavor of its subject spectacularly well. That subject is Rowland S Howard: songwriter and guitarist with The Birthday Party, Crime And The City Solution, and a idiosyncratic solo performer whose career was finally picking up some belated momentum when he died of liver cancer in 2009 aged 50. Howard’s story – of a brilliant talent whose career rewards were postponed indefinitely by his heroin dependence – is sad, but the strength of Autoluminescent is that it paints a vivid picture of Howard, (someone who, as Henry Rollins says here, was “spectral. Like Rimbaud back from Africa”, even when at full tilt), and the major influence he had: on the women he loved, the bands he played in, and the scenes he animated. Tall, wry, and convinced of his own greatness (he signed pictures of himself saying, “tomorrow belongs to me”) he arrived on the late 1970s Melbourne rock scene, as Nick Cave confirms in a warm, frank and vaguely confessional interview, fully formed. At 16, Howard wrote “Shivers”, a piece sending up faux-suicidal teenage angst, which impressed Cave to the point of admitting him to The Boys Next Door, the band that became The Birthday Party. A good chunk of the film, as you might hope, is dedicated to The Birthday Party, to whom Howard gave a white light guitar sound, several abstract compositions and a consumptive glamour. Suspecting their greatness, the band moved to London, (where Howard got malnutrition and all the bands were terrible), were too savage for New York (Howard: “In three gigs, we played 25 minutes. It was fantastic.”), and finally decamped to Berlin. Wim Wenders remembers them arriving “like Siberian crows” and featured Howard (now kicked out of the Birthday Party) prominently for his film (i)Wings Of Desire(i). These bits, as you might expect, look spectacular. Other groups (Crime And The City Solution; These Immortal Souls) and collaborations (with Lydia Lunch) followed, but Autoluminescent has sufficiently warmed us to the wry, charming Howard, his romantic nature and his sporadic bursts of greatness, that we are happy to spend the rest of the film on the gentler currents of his rather erratic life. There are some significant relationships with some good people, some solid pieces of work, some other projects begun, and a late surge of good fortune. Illness then makes its inexorable entrance into the piece. Autoluminescent is a superior documentary because it takes you down these inclines, off the beaten track of the more extreme contrasts of the “rise and fall” rock narrative. Rowland S Howard was a great musician, but all the big names pulled in to assure you of this can’t make him a household name, so the job that is accomplished here is necessarily a subtler one. It doesn’t show you Howard’s accomplishments as if they were arrayed in a trophy cabinet, or his addictions as if they were a torment heroically vanquished, but both as features in a wider life. The more you hear from the people close to him, the more a picture emerges of just who Rowland S Howard was, and why they miss him, and in so doing, why rock music continues to miss him too. John Robinson

The sad story of Roland S Howard, vividly told…

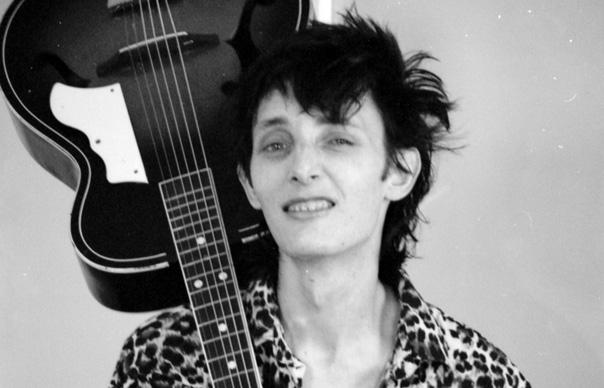

Romantic and beautiful, sad and funny, very cool and just a little bit pretentious – you’d have to say that Autoluminescent gets the flavor of its subject spectacularly well. That subject is Rowland S Howard: songwriter and guitarist with The Birthday Party, Crime And The City Solution, and a idiosyncratic solo performer whose career was finally picking up some belated momentum when he died of liver cancer in 2009 aged 50.

Howard’s story – of a brilliant talent whose career rewards were postponed indefinitely by his heroin dependence – is sad, but the strength of Autoluminescent is that it paints a vivid picture of Howard, (someone who, as Henry Rollins says here, was “spectral. Like Rimbaud back from Africa”, even when at full tilt), and the major influence he had: on the women he loved, the bands he played in, and the scenes he animated.

Tall, wry, and convinced of his own greatness (he signed pictures of himself saying, “tomorrow belongs to me”) he arrived on the late 1970s Melbourne rock scene, as Nick Cave confirms in a warm, frank and vaguely confessional interview, fully formed. At 16, Howard wrote “Shivers”, a piece sending up faux-suicidal teenage angst, which impressed Cave to the point of admitting him to The Boys Next Door, the band that became The Birthday Party.

A good chunk of the film, as you might hope, is dedicated to The Birthday Party, to whom Howard gave a white light guitar sound, several abstract compositions and a consumptive glamour. Suspecting their greatness, the band moved to London, (where Howard got malnutrition and all the bands were terrible), were too savage for New York (Howard: “In three gigs, we played 25 minutes. It was fantastic.”), and finally decamped to Berlin. Wim Wenders remembers them arriving “like Siberian crows” and featured Howard (now kicked out of the Birthday Party) prominently for his film (i)Wings Of Desire(i). These bits, as you might expect, look spectacular.

Other groups (Crime And The City Solution; These Immortal Souls) and collaborations (with Lydia Lunch) followed, but Autoluminescent has sufficiently warmed us to the wry, charming Howard, his romantic nature and his sporadic bursts of greatness, that we are happy to spend the rest of the film on the gentler currents of his rather erratic life. There are some significant relationships with some good people, some solid pieces of work, some other projects begun, and a late surge of good fortune. Illness then makes its inexorable entrance into the piece.

Autoluminescent is a superior documentary because it takes you down these inclines, off the beaten track of the more extreme contrasts of the “rise and fall” rock narrative. Rowland S Howard was a great musician, but all the big names pulled in to assure you of this can’t make him a household name, so the job that is accomplished here is necessarily a subtler one.

It doesn’t show you Howard’s accomplishments as if they were arrayed in a trophy cabinet, or his addictions as if they were a torment heroically vanquished, but both as features in a wider life. The more you hear from the people close to him, the more a picture emerges of just who Rowland S Howard was, and why they miss him, and in so doing, why rock music continues to miss him too.

John Robinson