SoCal boho's "alternative jungle music" finds its groove... First hoving into the wider rock consciousness via his titular appearance in Rickie Lee Jones's hit "Chuck E's In Love", Chuck E. Weiss is a longtime SoCal bohemian stalwart whose varied CV includes drumming for Lightnin' Hopkins and Wil...

SoCal boho’s “alternative jungle music” finds its groove…

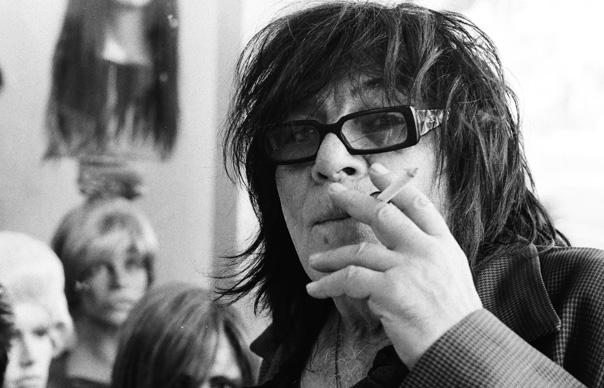

First hoving into the wider rock consciousness via his titular appearance in Rickie Lee Jones’s hit “Chuck E’s In Love”, Chuck E. Weiss is a longtime SoCal bohemian stalwart whose varied CV includes drumming for Lightnin’ Hopkins and Willie Dixon, deejaying on station KFML, hanging out with Marshall McLuhan, and establishing Hollywood’s legendary Viper Room back in 1993 with his chum Johnny Depp. His own music draws heavily on the kind of louche Americana Weiss covered in the History Of American Music class he used to teach at the University Of Colorado, enticingly titled “Flipsters, Hipsters, & Finger-Poppin’ Daddies”: a blend of R&B, jazz, cajun, jump blues, rumba, Tex-Mex and rockabilly that he dubbed “alternative jungle music”.

The belated follow-up to 2006’s splendid 23rd & Stout, Red Beans And Weiss was executive-produced by Depp and another of Chuck’s old chums, Tom Waits, though the latter’s influence is slightly less evident here than on previous albums. It features a more condensed approach, still eclectic but less eccentric – an engaging distillation of Weiss’s rumbustious style that locks the listener into a groove and doesn’t let go. “Tupelo Joe” opens the album with bathtub-amphetamine grace, a blast of raucous rockabilly R&B with a berserker edge that recalls The Cramps. A bastard child of Bo Diddley and Hank Mizell, it features dizbuster guitar licks of twangsome mien over simple, driving drums, while Chuck sings of how “Tupelo Joe went to the show, Tupelo Joe ain’t no shmoe,” and suchlike jive, the lyric eventually breaking down into staccato-stutter syllabic nonsense, like he’s talking in tongues.

In stark contrast, “Shushie” shifts into a 3am lounge-bar groove of loping double bass jazz guitar and sultry sax, Chuck’s intimate croon deriving as much sensual promise from the name as he murmurs his affection for the coolest of feline companions: “Shushie, Shushie, she’s hiding under the house/She’ll be in labour soon, without a spouse”. It’s the most relaxed thing here, the majority of the tracks cleaving to a more earthy groove, as exemplified by the lumpy, rolling funk-blues of “The Knucklehead Stuff”, or the low-slung rumba-rock R&B of “Bomb The Tracks”, which finds Weiss in unusually political mood – albeit filtered through a boho sensibility – as he chides Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt for not trying harder to stop the Holocaust death-camp deliveries: “Why didn’t you bomb the tracks, Jack? Why didn’t you stop the trains, James?…Hey, you know I’m a devout coward, and I would have bombed them tracks”.

Elsewhere, “Hey Pendejo” is a Doug Sahm-style Tex-Mex two-step, while Weiss gets to indulge both his scat-singing fancy in the jazzy “Oo Poo Pa Do In The Rebop”, and his Little Richard wail on the swinging boogie “Dead Man’s Shoes”. The raw, gritty R&B of “Boston Blackie”, meanwhile, brings to mind Tom Waits’s Heartattack & Vine with its scarified slide-guitar stomp. Emulating the eponymous pulp-fiction gumshoe’s claim to be “friend to those who have no friends”, it’s an opportunity for Chuck to extemporise a lengthy litany of names that gets more ludicrously amusing the longer it extends: “Freddie, Eddie, Mary, Sarah…”, and so on, and on.

Chuck’s time playing with Dr John pays dividends on “The Hink-A-Dink”, a distinctly un-PC portrait of dancing jungle natives led by “a cool native chieftain with a bone through his nose” that perhaps best conveys his notion of “alternative jungle music”. With violin slithering snake-like through an undergrowth of low, sinister humming and wordless female backing wails, it sounds like nothing so much as an outtake from Gris-Gris. Another satisfying encapsulation of the Weiss aesthetic comes on a great version of the Stones’ outtake fragment “Exile On Main Street Blues”, which starts out as a basic Memphis piano blues, Chuck’s voice strained and distant, as if heard through an antique speaker, before the drums and riffing horns roll in after the first verse and drive it up to Chicago in a sleek sedan: a brilliant musical allegory of the northward drift of black Americans seeking liberation from Southern poverty and prejudice, evoked with a proud, empathic swagger.

Andy Gill