Swamp-pop goes Woodstock: Louisiana legend's rarely heard '72 masterpiece with The Band... As much rumor as album, vanishing for decades from the moment it was released, Bobby Charles is a mythic missing link — between Mardi Gras and hippie denouement, the Crescent City's fabled "Second Line" and '70s singer/songwriter — a funky, bluesy, laconic masterpiece fusing genteel delta wistfulness with barbed wit and a sly, post-apocalypse vibe. That it fell through the cracks isn't surprising: Charles' reclusive, waiflike personality and aversion to touring hardly hardwired him for rock stardom; that its sentiments resonate more in 2014 than in 1973 mark it as a timeless, enigmatic classic. The irony is that had Charles not been on the lam from a Nashville pot bust, the record wouldn't exist. But Rick Danko and his esteemed Woodstock circle — John Simon to Bob Neuwirth, David Sanborn to Geoff Muldaur, plus fine backing musicians from Ian & Sylvia's Great Speckled Bird: guitarist Amos Garrett, bassist Jim Colegrove, drummer N.D. Smart — were in on the secret: As Robert Charles Guidry, Charles had written some of the most exciting, enduring hits of the early rock era: "See You Later, Alligator" (Bill Haley), "(I Don't Know Why I Love You) But I Do" (Clarence 'Frogman' Henry), "Walking to New Orleans" (Fats Domino). This later Bobby Charles, spending much of 1973 writing songs, sleeping on Colegrove's couch, recording at Albert Grossman's Bearsville Studio, was a different animal, though, a laconic, ramblingly philosophical soul who fit right in with the erstwhile Hawks, who'd spent their pre-fame years — think 1967-68 — concocting Bob Dylan's deep yet similarly off-the-cuff Basement Tapes. As everyone duly discovered, Charles' songs were subtly devastating, powerfully deceptive, textured to disarm even the most skeptical detractor. Relaxed, stoned-out grooves, rustic easygoing yet quirky takes on New Orleans' classic sound, dominate the proceedings. The presentation is loose, airy, with plenty of room for Dr. John's piano or Ben Keith's pedal steel to dance eloquently around Charles' serpentine melodies, or for Smart or Levon Helm to assert their downhome, funky, rhythmic stamp. At times, like on "Street People," "Up on Cripple Creek"'s cousin, or the gentle, drop-dead gorgeous "Tennessee Blues," the sessions sound like The Band amid hearty rounds of red wine. On the latter, mellifluous, abetted by Garth Hudson's superb accordion, Charles sings with a longing for the ages. On others — the infectious "Before I Grow Too Old," with crashing electric guitar and Sanborn sax — the combo trips along like a tipsy, high-on-life Bourbon Street bar band. "I'm gonna do a lot of things I know is wrong," Charles whoops in his backwoods, country-boy dialect. Yet for all the Louisiana soul seeping into the grooves, Bobby Charles also doubles as The Band's (sans Robertson) lost album. The parent group was spent, heading out on a long sabbatical; but here sundry individuals could exit the rat race, invade the studio with old friends. Even if Danko/Hudson/Helm/Manuel weren't all always on board (true credits remain murky), their vibe is everywhere, the idyllic extended Woodstock musical family come to life. Charles, meanwhile, is inscrutable. Deftly delivering deep-in-the-pocket vocals, seemingly offhandedly — even pulling off mic sometimes — he's the personification of less-is-more. Jabs of humor emerge, sly hooks land permanently in your cranium, and canny social commentary — on greed, hypocrisy, duplicity, blind ambition — bubbles up. While the dreamy, floating-on-a-cloud love songs ("I Must Be in a Good Place Now") are uncomplicated, Zen in approach — "Oh what a good day to go fishin'" — he posits, ironically — the trouble starts when the power-mongers start throwing their weight around. The bluesy "He's Got All the Whiskey" pricks at what we'd now call the one percenters, while "Street People" salutes those unwilling to play the rat-race game before leaning sardonically into the punchline: "Some people would rather work/We need people like that!" "Save Me Jesus" may be the most unconventional protest music ever, its message wrapped in seesawing, rocking R&B. "So when you take me Jesus," Charles pleads, "Please put me among friends/Don't put me back with these power crazy money-lovers again." The minimalist "Small Town Talk," a Charles/Danko co-write, Dr. John on skipping organ trills, boils it all down, echoing small truths Dylan and The Band danced around on the Basement Tapes: "Who are we to judge one another?" Charles coos in a lilting croon. "That could cause a lot of hurt." Luke Torn Q&A Jim Colegrove What kind of guy was Bobby Charles? Bobby was one of the friendliest guys I’ve ever met. As we came to know each other he told me, in his thick Cajun accent, that he’d been living with his wife and son in Nashville. He’d been busted for possession of marijuana and charged with dealing, jumped bail, and took flight to the north. I began to see he was looking for someone with the power to make a deal for him to square the charges. It didn’t take long for Bobby to see that man was Albert Grossman. What did you think his songwriting? Bobby wrote songs, but he didn’t play an instrument. He’d start singing his songs and you had to find his key and find the changes by ear! If you made a wrong change, he would correct you until you got the right one. It was in this manner I learned the new songs he’d written. . . . We weren't thinking so much about making a record as much as doing a songwriter's demo. It escalated to a full-fledged project as time passed. Who organized the sessions? Bobby wanted N.D. Smart, Amos Garrett, and me to play with him. As you may or may not know, the three of us were in Great Speckled Bird together and N.D. and I had been playing together for seven years at that time. I don't recall how John Simon got into the picture but Dr. John was a friend of Bobby's from way back. Luke Torn

Swamp-pop goes Woodstock: Louisiana legend’s rarely heard ’72 masterpiece with The Band…

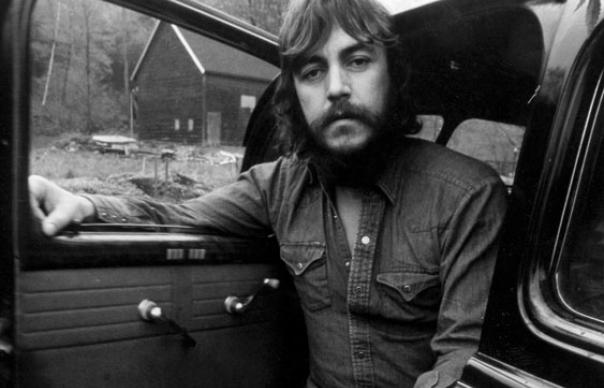

As much rumor as album, vanishing for decades from the moment it was released, Bobby Charles is a mythic missing link — between Mardi Gras and hippie denouement, the Crescent City’s fabled “Second Line” and ’70s singer/songwriter — a funky, bluesy, laconic masterpiece fusing genteel delta wistfulness with barbed wit and a sly, post-apocalypse vibe. That it fell through the cracks isn’t surprising: Charles’ reclusive, waiflike personality and aversion to touring hardly hardwired him for rock stardom; that its sentiments resonate more in 2014 than in 1973 mark it as a timeless, enigmatic classic.

The irony is that had Charles not been on the lam from a Nashville pot bust, the record wouldn’t exist. But Rick Danko and his esteemed Woodstock circle — John Simon to Bob Neuwirth, David Sanborn to Geoff Muldaur, plus fine backing musicians from Ian & Sylvia’s Great Speckled Bird: guitarist Amos Garrett, bassist Jim Colegrove, drummer N.D. Smart — were in on the secret: As Robert Charles Guidry, Charles had written some of the most exciting, enduring hits of the early rock era: “See You Later, Alligator” (Bill Haley), “(I Don’t Know Why I Love You) But I Do” (Clarence ‘Frogman’ Henry), “Walking to New Orleans” (Fats Domino).

This later Bobby Charles, spending much of 1973 writing songs, sleeping on Colegrove’s couch, recording at Albert Grossman’s Bearsville Studio, was a different animal, though, a laconic, ramblingly philosophical soul who fit right in with the erstwhile Hawks, who’d spent their pre-fame years — think 1967-68 — concocting Bob Dylan’s deep yet similarly off-the-cuff Basement Tapes.

As everyone duly discovered, Charles’ songs were subtly devastating, powerfully deceptive, textured to disarm even the most skeptical detractor. Relaxed, stoned-out grooves, rustic easygoing yet quirky takes on New Orleans’ classic sound, dominate the proceedings. The presentation is loose, airy, with plenty of room for Dr. John’s piano or Ben Keith’s pedal steel to dance eloquently around Charles’ serpentine melodies, or for Smart or Levon Helm to assert their downhome, funky, rhythmic stamp.

At times, like on “Street People,” “Up on Cripple Creek”‘s cousin, or the gentle, drop-dead gorgeous “Tennessee Blues,” the sessions sound like The Band amid hearty rounds of red wine. On the latter, mellifluous, abetted by Garth Hudson’s superb accordion, Charles sings with a longing for the ages. On others — the infectious “Before I Grow Too Old,” with crashing electric guitar and Sanborn sax — the combo trips along like a tipsy, high-on-life Bourbon Street bar band. “I’m gonna do a lot of things I know is wrong,” Charles whoops in his backwoods, country-boy dialect.

Yet for all the Louisiana soul seeping into the grooves, Bobby Charles also doubles as The Band’s (sans Robertson) lost album. The parent group was spent, heading out on a long sabbatical; but here sundry individuals could exit the rat race, invade the studio with old friends. Even if Danko/Hudson/Helm/Manuel weren’t all always on board (true credits remain murky), their vibe is everywhere, the idyllic extended Woodstock musical family come to life.

Charles, meanwhile, is inscrutable. Deftly delivering deep-in-the-pocket vocals, seemingly offhandedly — even pulling off mic sometimes — he’s the personification of less-is-more. Jabs of humor emerge, sly hooks land permanently in your cranium, and canny social commentary — on greed, hypocrisy, duplicity, blind ambition — bubbles up.

While the dreamy, floating-on-a-cloud love songs (“I Must Be in a Good Place Now”) are uncomplicated, Zen in approach — “Oh what a good day to go fishin'” — he posits, ironically — the trouble starts when the power-mongers start throwing their weight around.

The bluesy “He’s Got All the Whiskey” pricks at what we’d now call the one percenters, while “Street People” salutes those unwilling to play the rat-race game before leaning sardonically into the punchline: “Some people would rather work/We need people like that!” “Save Me Jesus” may be the most unconventional protest music ever, its message wrapped in seesawing, rocking R&B. “So when you take me Jesus,” Charles pleads, “Please put me among friends/Don’t put me back with these power crazy money-lovers again.”

The minimalist “Small Town Talk,” a Charles/Danko co-write, Dr. John on skipping organ trills, boils it all down, echoing small truths Dylan and The Band danced around on the Basement Tapes: “Who are we to judge one another?” Charles coos in a lilting croon. “That could cause a lot of hurt.”

Luke Torn

Q&A

Jim Colegrove

What kind of guy was Bobby Charles?

Bobby was one of the friendliest guys I’ve ever met. As we came to know each other he told me, in his thick Cajun accent, that he’d been living with his wife and son in Nashville. He’d been busted for possession of marijuana and charged with dealing, jumped bail, and took flight to the north. I began to see he was looking for someone with the power to make a deal for him to square the charges. It didn’t take long for Bobby to see that man was Albert Grossman.

What did you think his songwriting?

Bobby wrote songs, but he didn’t play an instrument. He’d start singing his songs and you had to find his key and find the changes by ear! If you made a wrong change, he would correct you until you got the right one. It was in this manner I learned the new songs he’d written. . . . We weren’t thinking so much about making a record as much as doing a songwriter’s demo. It escalated to a full-fledged project as time passed.

Who organized the sessions?

Bobby wanted N.D. Smart, Amos Garrett, and me to play with him. As you may or may not know, the three of us were in Great Speckled Bird together and N.D. and I had been playing together for seven years at that time. I don’t recall how John Simon got into the picture but Dr. John was a friend of Bobby’s from way back.

Luke Torn