By the time Anne Briggs came to record this, her second album proper, she was already on her way out of a folk scene she had helped transform during the 1960s, when she had flitted through Albion’s folk clubs and pubs like an untamed nature spirit. Belonging to country rather than town, disinclined to stay anywhere for long, Briggs had a mercurial quality that chimed with the strangeness of English folksong – it was easy to imagine encountering her materialising in the mists above Blackwater Side or rambling through the greenwood, lurcher in tow, exactly as the cover of The Time Has Come depicts her. The urge for freedom that would lead her to vanish (leaving a third album complete but unissued) was there in her singing. Blessed with a skylark of a voice that was usually unaccompanied, Briggs would inhabit a song rather than deliver it note perfect. It was a quality better suited to the traditional fayre with which she made her name than to the originals and covers here – her versions of “Reynardine” and the rest remain timeless, whereas The Time Has Come gets by more on period charm. By this time Anne was accompanying herself – adequately but no more - on guitar and (unusually for 1970) bazouki. The real problem is material too slight for her wildness. “Fire and Wine”, borrowed from a friend, is a campfire singalong, “Ride Ride” a tepid re-run of “Railroad Bill”, “Everytime” and “Tidewave” half-formed ideas. Add a couple of ho-hum instrumentals and you’re half an album down. The remainder, though, has real strength. The title track – already covered by Pentangle among others – retains an easy charm, and “Tangled Man”, “Wishing Well” (written with Bert Jansch) and “Sandman’s Song” show a songsmith in the making. Best of all comes Lal Waterson’s “Fine Horseman”, whose mood of languid romance is perfectly captured by vocals that ripple with love and lust. An imprefect creation, then, but one of immense charm. NEIL SPENCER

By the time Anne Briggs came to record this, her second album proper, she was already on her way out of a folk scene she had helped transform during the 1960s, when she had flitted through Albion’s folk clubs and pubs like an untamed nature spirit.

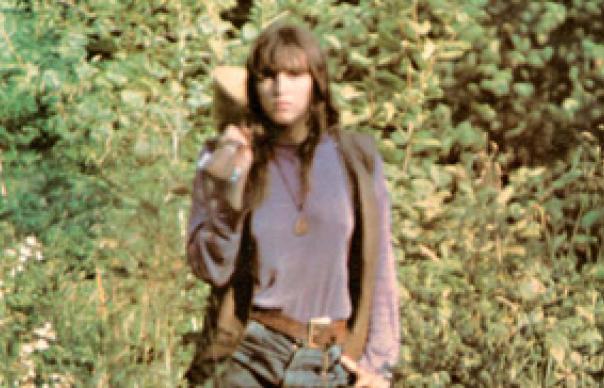

Belonging to country rather than town, disinclined to stay anywhere for long, Briggs had a mercurial quality that chimed with the strangeness of English folksong – it was easy to imagine encountering her materialising in the mists above Blackwater Side or rambling through the greenwood, lurcher in tow, exactly as the cover of The Time Has Come depicts her.

The urge for freedom that would lead her to vanish (leaving a third album complete but unissued) was there in her singing. Blessed with a skylark of a voice that was usually unaccompanied, Briggs would inhabit a song rather than deliver it note perfect.

It was a quality better suited to the traditional fayre with which she made her name than to the originals and covers here – her versions of “Reynardine” and the rest remain timeless, whereas The Time Has Come gets by more on period charm.

By this time Anne was accompanying herself – adequately but no more – on guitar and (unusually for 1970) bazouki. The real problem is material too slight for her wildness. “Fire and Wine”, borrowed from a friend, is a campfire singalong, “Ride Ride” a tepid re-run of “Railroad Bill”, “Everytime” and “Tidewave” half-formed ideas. Add a couple of ho-hum instrumentals and you’re half an album down.

The remainder, though, has real strength. The title track – already covered by Pentangle among others – retains an easy charm, and “Tangled Man”, “Wishing Well” (written with Bert Jansch) and “Sandman’s Song” show a songsmith in the making. Best of all comes Lal Waterson’s “Fine Horseman”, whose mood of languid romance is perfectly captured by vocals that ripple with love and lust. An imprefect creation, then, but one of immense charm.

NEIL SPENCER