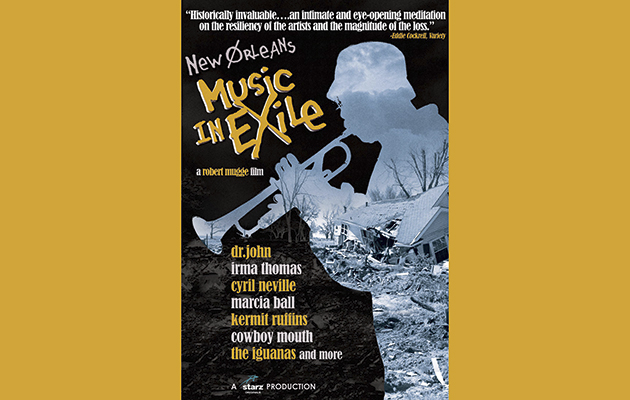

“This is a different city now,” says the man from Basin Street Records, midway through Robert Mugge’s deeply humane documentary about the impact of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on the musical culture of Crescent City. “Everybody lost something.” Originally released in 2006 and now available ...

“This is a different city now,” says the man from Basin Street Records, midway through Robert Mugge’s deeply humane documentary about the impact of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 on the musical culture of Crescent City. “Everybody lost something.”

Originally released in 2006 and now available on Blu-Ray, Mugge’s film is part musical history lesson, part lament, part balm and part rallying cry. Its central thesis is a persuasive one: that New Orleans is the most diverse musical environment in the United States (Cyril Neville claims that it’s not really part of America at all, but is instead “the northernmost point in the Caribbean”). Throbbing with Cajun, zydeco, funk, jazz, R&B and blues, it boasts several venerable music bloodlines, not least the Neville clan. Here, music is not merely a pleasant add-on, but the heartbeat of the city. When Katrina hit, the lifeblood of New Orleans stopped pumping. To get healthy again, the music needed to spark back into life.

Filming in Katrina’s immediate aftermath, Mugge’s empathetic camera finds a city on its knees. The sheer devastation – physical, human, emotional – wreaked by the storm still retains the power to shock. “Like left over footage from Hiroshima,” says Dr John, one of dozens of local luminaries featured. Many are interviewed in exile. One of the most pleasing of the film’s strands tells how the surrounding music communities rally around. Clubs in La Fayette, Austin, Houston and Memphis pick up the slack and give musicians like Cyril Neville and The Iguanas places to play – and often, to stay.

We hear their personal stories of the storm hitting. Many had followed the news while they were on the road, watching from a distance as friends and family evacuate and drop out of contact. One musician is told there is a boat on his roof and another on his lawn. Another returns to his mother’s house to find a car in the swimming pool. His own home is 20 feet from where he’d left it.

Those who stayed behind or quickly returned face profound trauma. Irma Thomas surveys the ruins of her club, the Lion’s Den, which looks like it has suffered a direct strike in a warzone. Her home is even worse, half-eaten by mould. Eddie Bo re-enters the coffee house he owned and finds it unsalvageable. “Just let it go,” he says to his distraught sisters. “Don’t go back in there ever again.”

This is not a starry film. Its primary focus are local musicians, and their supporters and enablers at grass roots level. Mugge drops in on OffBeat magazine, the Times Picayune newspaper, Basin Street Records and Red Cat Jazz Café as they come to terms with the wreckage. Post-Katrina, New Orleans is “an amputee with phantom memory,” says David Freeman from local radio station WWOZ.

At a time when many areas in the city still have no gas, no postal service, no telephones and little hope, focusing on music might seem trivial, but it becomes obvious that it’s a vital part of the recovery of the city. The amount of sheer good will on display is moving, from numerous individual kindnesses to Music Cares providing grants for living expenses and new equipment. Slowly, flyers appear on telegraph poles and venues begin to re-emerge from the rubble. The august Maple Leaf Bar opens its doors despite having no power. It makes do with a generator, fairy lights and beer on ice. More than a thousand people come to dance, and celebrate the first signs that the city is stirring again.

Music In Exile is a little overlong – Mugge clearly wanted to honour as many of these stories as he could – and has odd absences. Allen Toussaint is barely mentioned, and though the lack of a political agenda is perhaps understandable, without one it feels like an important part of the story isn’t being told. The music, however, is glorious – there are affirming live performances from Irma Thomas, Cyril Neville, Dr John, Eddie Bo, Marcia Ball, John Cleary and The Iguanas, among others – and it concludes on a note of cautious optimism. This is a population well accustomed to dancing in the face of death, and the city’s fatalism stands it in good stead. “We’re planning on coming back stronger,” says Dr John. In the decade since he drawled those words, New Orleans has won some battles and stills faces many more. Perhaps a sequel to this fine film is overdue?