A few moments before it alights on a rooftop sunbather in a bikini, the roving aerial camera of R Lee Frost’s 1966 movie Mondo Bizarro makes its way down an unprepossessing street of dawdling traffic and shabby sun-bleached awnings. We see a minibus parked. There are a couple of Volkswagens. �...

A few moments before it alights on a rooftop sunbather in a bikini, the roving aerial camera of R Lee Frost’s 1966 movie Mondo Bizarro makes its way down an unprepossessing street of dawdling traffic and shabby sun-bleached awnings. We see a minibus parked. There are a couple of Volkswagens.

“This,” an actorly narration informs us, “is Sunset Boulevard, legendary street of dreams and myths. Young people from all over the world are drawn here by the glamour and the film industry. For this is Hollywood. Here are the fabled clubs and watering places of the celebrated…”

Fabled? Celebrated? It doesn’t look that way. Still, as the camera moves, it accidentally catches something of particular historical interest above the frontage of The London Fog, the newest but also paradoxically the shabbiest of the clubs on the strip. It’s a red sign which reads: “The Doors”, announcing a new band from the city, then in residence.

It’s an enchanting, and exciting moment, and this current release has much of the same qualities. Recorded at the club by a UCLA student named Nettie Peña, whose father had passed his enthusiasm for audio recording on to his daughter, The Doors were on this night near the start of their first professional engagement, their performance supported by friends from the university.

As with the Sex Pistols at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall, there’s a degree of mythology in play with an event like this. Nettie herself in her sleevenotes recalls it being a standing-room-only kind of event, although the tape suggests a more sparse turnout. In 1972 Ray Manzarek recalled that the club was no thriving concern. This was the sort of place you’d find in a Tom Waits song: peopled by the odd drunk, serviceman or prostitute, but not generally by bands going places. This tape is said to come from May near the end of the band’s run – the band first auditioning in late February, and then playing throughout March and April.

By mid-May, the band were let go by the London Fog, the club closing shortly afterwards. But this was not before The Doors had been checked out by Ronnie Haran, who booked the considerably more prestigious Whiskey-A-Go-Go club nearby. Haran wouldn’t sit down in the London Fog (“I might get crabs,” she apparently said at the time), but was blown away by the band. Ray Manzarek said she fell instantly in love with Jim Morrison. Haran today says she fell instead for Manzarek’s playing.

The Doors were at this stage fuelled-up and on the runway, but not yet taken off. The previous year the band had made a rudimentary five-song demo, which had won them a contract with CBS (which would not ultimately be taken up). More significantly, they had just secured the services of another UCLA student, Robby Krieger, to play guitar, who now added his tangential blues to songs like “Moonlight Drive” and “Hello, I Love You”.

Listening to The London Fog captures their evolving promise. This clearly isn’t yet The Doors of another officially-released early live show, Live At The Matrix, 1967. There, the young band offer a full and discursive hour-and-a-half display of their powers from “The End” to “Crawling King Snake”, their own compositions politely blowing the minds of lightly-applauding turtlenecked hipsters at an all-seater San Francisco nightclub.

As with that release, there’s an interesting insight into which were the band’s earliest songs. Here, amid the covers that make up the majority of the half-hour recording, there’s a reading of “Strange Days”, which is already much as it would appear on the band’s second album, down to Ray Manzarek’s ornate organ intro. It’s magnificent, and clearly a very different order of thing than what has previously transpired in the set. It unfolds with the dark ellipsis of a short story – which is probably why it’s greeted with what, hand on heart, you’d have to report as nothing more than polite applause. The other original composition in the seven here is “You Make Me Feel Real”, which wouldn’t show up until Morrison Hotel four years later.

It’s a minor song, a basic 12-bar rocker, but it gets a far better reception, an innocent fact which won’t have gone unnoticed by the band as they worked on their evolving stagecraft. It’s probably this which is the revelation of The London Fog. We’re not so much hearing the heft of a fully-formed, not yet famous group, as we did with the Matrix recordings, but instead one which has a talent, charisma and presence already very much working for it, even if all the material isn’t quite there yet.

After some tuning, the opener “Rock Me”, a take on BB King’s song from two years previously, shows just how the band can open up a song to create their own space and drama. The logical end of this were the band’s extended excursions on “The End” and “Light My Fire” (it is at this point Nettie Pena becomes in a small way the villain of the piece – a second reel of this performance containing “The End” and possibly “Moonlight Drive” has got waylaid during a house move somewhere at some point in the last 50 years), but here the band set quite their own pace and style.

Like other bands of the period, blues was their starting point, but piloted by Manzarek’s entropic musicality and Robby Krieger’s intrepid noise The Doors leave it quicker than most. “Baby Please Don’t Go” isn’t, in principle, going to offer huge surprise to anyone familiar with blues-based music of the 1960s. However, Morrison’s innate theatricality draws you in, as the volume lowers, to focus attention on the singer as the conductor of events (“the shaman”, as Manzarek recalled the young Jim). It was a dramatic resource on which he and the band would draw throughout their existence.

Their swinging take on Wilson Pickett’s “Don’t Fight It” does something similar, but in a tempo which throws forward to “Love You Two Times”. Elsewhere, the impression is of a band with a particular dynamism and a burgeoning confidence – to the point where they are happy to let the keyboard player sing “Hoochie Coochie Man”, and not the singer.

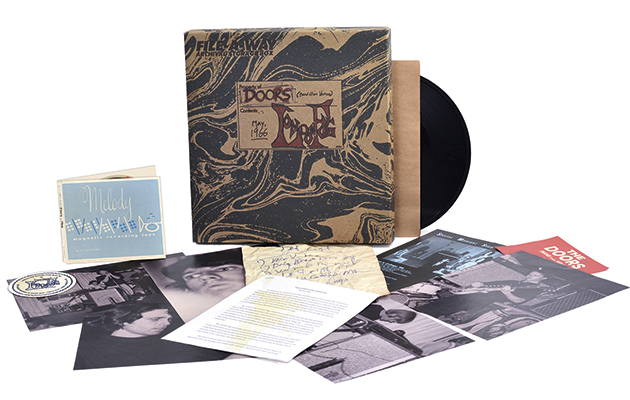

All round, it’s more than the sum of its parts, if not quite the event that is clearly hoped for – and as the facsimile packaging, 10” vinyl release and so forth might encourage you to believe. Discovered in 2011 this has clearly been awaiting the right occasion to bolster its release. The 50th anniversary of The Doors now provides just that – along with the welcome reminder that a release such as this doesn’t have to be completely mindblowing for it to be quietly historic.

Q&A

ROBBY KRIEGER

By the time of these recordings, you’d been in the group maybe six months, right?

Was it that quick? When I got in the group they already had four or five songs and I added my guitar and changed them a little bit. Then at one point Jim said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna need more songs, you should write some too. It was the first time I thought about writing. I went home and wrote “Light My Fire” which worked out pretty good, and the second was “Love Me Two Times”… “You’re Lost Little Girl”… This was all in a couple of months of joining the group.

Tell me a bit more about writing “Light My Fire”.

I was living with my parents in Pacific Palisades – I had my amp and SG guitar. I asked Jim what should I write about? He said, write about something universal, which won’t disappear two years from now. Something that people can interpret for themselves. I said to myself I’d write about the four elements: earth, air, fire, water. I picked fire, because I loved the Stones song “Play With Fire”, and that’s how that came about.

How would you write back then?

One time Jim came and stayed at my house when my parents went on a trip and we wrote “Take It As It Comes”, “Strange Days”, lot of cool songs, a couple months later. “The End” was written at that time, which was a love song at that time about a guy breaking up with his girlfriend. Usually, he would have an idea for the lyrics and I would put what I heard as the music. It always seemed to work. When I had something, he always made it better.

Did the London Fog gig feel like a big break?

It did at first, because it was a club on the strip, a new one. It wasn’t the status of the Whiskey or something, but there it was, only a block away. We thought it was pretty cool…until the second night. The first night, we must have had 100-150 people and after that, the second night, nobody. And over the next couple of weeks maybe a couple sailors would come in. It was pretty boring, but it was good because we could play our own songs and work ’em up – it wasn’t like we were rehearsing, we had to play them – in case anybody actually came in. But it was disappointing that we weren’t building up a following. I guess it was a new club, people didn’t know to come in.

What strikes you about the young Doors?

It sounds very raw, obviously, but you can definitely tell it’s us. We were making mistakes and stuff. Ray was singing a lot at that time, and was a little bit out of tune. Jim, even though his voice wasn’t fully developed yet, he had the chops: he could go real high and had that low croony thing going on. The sound is actually pretty good for an audience recording. What I think is pretty cool is when we finish a song and you hear like…three people clapping.

Were you impressed with Jim?

At first no, but as the residency continued, he really came out of his shell. I think that must have been after we did it for a couple of weeks. It was probably towards the end of the run. He was definitely beginning to feel it by then. He used to be very shy, he wouldn’t even look at the audience – his back was turned. When we rehearsed at home, we rehearsed in a circle, so we could look at each other and he would know when to come in. You can’t do that on stage. Eventually he turned around and started interacting with the audience.

Tell me about your experience of the blues?

When I started playing guitar I started playing flamenco music which I really loved. But I had a couple of buddies who were playing steel string guitar, they were trying to get into blues, and we all discovered these old records – one of the guy’s dads had a bunch of old records. I really liked Blind Willie Johnson, who played slide guitar, a blind guy, and Robert Johnson, of course. I didn’t try to emulate them especially but I did love the slide and experimenting with that. I didn’t want to do what those guys were doing, but I thought that sound would work with rock’n’roll. So “Moonlight Drive” was an important song for us, it was actually the first song we played together, the four of us, when we got together for the first time. That was all it took, man, they loved that sound – they wanted it on every song.

You played that at the London Fog, I presume?

Yeah. Unfortunately, half of the songs have not been found yet. There were two tapes, but only one has been found. I had no memory of Nettie Peña – I was in the regular school not the film school, I was younger than them. I heard that some tapes had been found. All this time we’ve been trying to find the other tape. We haven’t stopped looking. It’s gotta be in her storage in her house somewhere. I should probably go over there with a magnetometer…We’ve known about it all this time, it’s pretty frustrating. There was a guy at the Whiskey who recorded a lot of stuff, John Jernick, and no-one knows what happened to him, or his tapes. There’s nothing from the Whiskey – he did the sound there, he was an audio freak and he made tapes – so somebody’s got it.

How does it feel to be approaching your 50th anniversary?

It doesn’t feel like 50 years. It’s cool that it’s lasted this long. What moves me when people say things like The Doors changed my life – it feels great when you’ve affected people positively that much.

INTERVIEW: JOHN ROBINSON