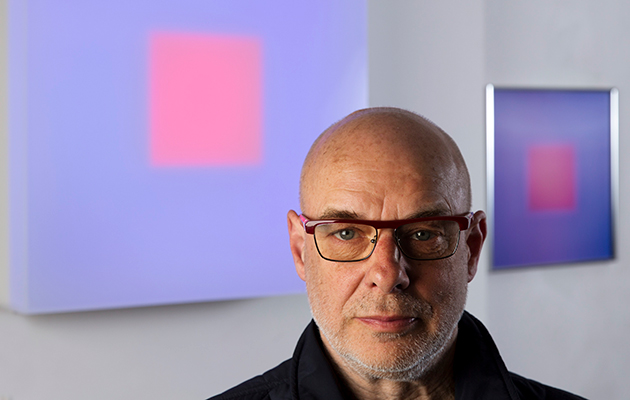

In February this year, Brian Eno unveiled his latest project: an immersive installation modelled on Bloom, his 2008 generative music app co-created with Peter Chilvers. Using virtual reality headsets, visitors to Bloom: Open Space could fashion Augmented Reality bubbles – ‘blooms’ – that burst into being with a musical note before floating heavenwards. Like all good art, the installation asked a number of searching questions of its participants. Chief among these regarded the hierarchy of the creative process: what is more important here, the people, the music they made or the technology that enabled them to make it?

Similarly, Music For Installations comes with its own set of questions for the listener. Assembled over six discs, it mostly features material Eno used in his art projects from 1986 to the present day. So how do these particular pieces interact and overlap with Eno’s other creative disciplines? Eno’s 2016 album The Ship, for instance, began life as a music installation at Barcelona’s Fundació Antoni Tàpies that was, he outlined, an attempt to unite the “three different threads of [his] career: the creation of pop music, with songs; creating ambient music, without lyrics; and installations”. The Ship itself was one of Eno’s very best records; but at what point did music for an installation become an album?

It’s possibly to detect something of The Ship’s submarinal tones in “Kazakhstan” (they’re roughly contemporary pieces), particularly the electronic creaks and glum sonar pulses. “Atmospheric Lightness” and “Chamber Lightness” are both from a 1997 installation at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg and unfold in the same mournful, minor key register. Originated for Helsinki’s Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art; “Kites I” through to “Kites III” are meditations on the same four note sequence. But although these are otherwise unconnected pieces – a assembled from shows in London, Tokyo, Italy and elsewhere – they all have a shared textural feel and a slow unfolding like rolling electronic fog. Only on “77 Million Paintings” might you suddenly discern a heavily treated human (?) voice in the background, or what sounds like someone sawing wood.

Some of the material here has already been released as limited run CDs – like 2010’s Making Space, which takes up Disc 5 and was first sold at venues exhibition 77 Million Paintings. It is unique here in featuring actual musicians – Leo Abrahams on guitar and Tim Harries on bass – although their organic contributions are ghostly scratchings on the bed of electronica shifting beneath them. This being Eno, Disc 6 comprises music for future installations; titles including “Unnoticed Planet” and “Sour Evening (Complex Heaven 3)” suggest the hand of a computer algorithm, an extension of Eno’s generative music experiments. These experiments, which dot Music For Installations, present yet another line of inquiry: can artificially generated compositions be as effective as pieces made by human hand? It is a question you suspect that Brian Eno – always one step ahead of the game – already has an answer to.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner