After leaving Roxy Music in July 1973, Brian Eno hatched a number of audacious schemes to launch his new career. There was – he revealed to NME’s Nick Kent – Luala And The Lizard Girls, who would perform live in launderettes and massage parlours, and the Plastic Eno Band, dedicated to creating music from an assortment of plastic musical instruments. Among other supposed works-in-progress were ‘The Magic Wurlitzer Synthesizer Of Brian Eno Plays “Winchester Cathedral” And 14 Other Evergreens’, a collaboration with Lynsey De Paul and even a rapprochement with estranged former bandmate Bryan Ferry as a duo called The Singing Brians.

But of all the many fabrications Eno proposed to Kent, one of them actually turned out to be true: a collaborative album with Robert Fripp. Released in November 1973, Fripp & Eno’s (No Pussyfooting) was the first record to carry Eno’s name post-Roxy. It established a pattern for the next 40-plus years – Eno as the inveterate collaborator. Between 1974 and 1977 alone – from Here Come The Warm Jets to Before And After Science – Eno’s assiduous creative networking led to assignations with, among others, John Cale, Cluster, Genesis, Nico, Robert Wyatt, Television, Hawkwind’s Robert Calvert, Gavin Bryars, Ultravox! and David Bowie.

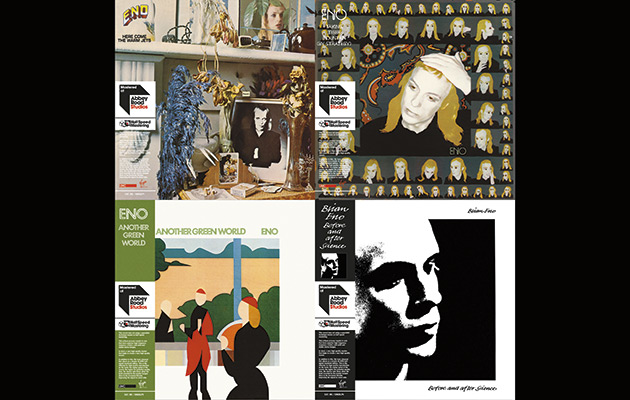

Given this, it’s hard to believe Eno had time for his own career. Yet his first four ‘vocal’ albums are significant; not just in establishing Eno as a solo artist but also for the way they bridge musical worlds, bringing together the electronic and the organic, rock and drone, truffling out unexpected connections between incongruent styles. Eno’s catalogue was remastered for CD in 2004, but these are the first new vinyl cuts of these four LPs since the mid-1980s – with each album now spread over two discs – and have now been mastered at half-speed, a process designed to enhance the depth of field for vinyl reissues. The LP that benefits most obviously from this improved treatment is Another Green World, which enjoys a heightened immersive experience. The others sound fuller, richer; they’re louder, the volume has been raised, but there’s no compression or unnecessary EQing.

“I didn’t see Bowie and Lou as my peers”: Click here to read Uncut’s interview with Brian Eno

For January 1974’s Here Come The Warm Jets, Eno surrounded himself with old associates, including Andy Mackay and Phil Manzanera. The album covers plenty of ground – art pop, doo-wop pastiche, drones and surreal exotica – sometimes, like “Cindy Tells Me”, all within the space of one song. But Eno makes a virtue of these disparate qualities, stacking the absurd next to the sinister. Eno’s voice, previously glimpsed during harmonies on Roxy records, was now presented as another stylistic component, deployed in exaggerated fashion to suit each song: a sinister whine on “Baby’s On Fire”, a droll croon on “Dead Finks Don’t Talk”, multi-tracked into soothing symphony on “Some Of Them Are Old”. The wistful “On Some Faraway Beach”, meanwhile, offered an emotional counterpoint to his arch, self-aware creations.

Eno refined his working practices further for November 1974’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), working with a smaller core band, including Manzanera and Wyatt. The emphasis was still on creative spontaneity; the newly devised Oblique Strategies instruction cards encouraged additional lateral thinking. Very loosely inspired by a series of postcards from a Chinese revolutionary opera, Taking Tiger Mountain… foregrounds unusual instruments in its pursuit of fresh perspectives. Manzanera’s guitar is still prominent – especially on the frenetic “Third Uncle” – but keen listeners might spot the typewriter solo on “China My China”, the Portsmouth Sinfonia’s string section on “Put A Straw Under Baby” or the noise like robot crickets stridulating at the end of “The Great Pretender”.

1975 proved to be an auspicious year for Eno. An accident in January led – fortuitously – to his inaugural ambient work, Discreet Music, whose textural drift seeped into the gentle rhythms of September’s Another Green World. Only five of the 14 songs have vocals and these tend to be delivered in soft, hymnal tones – like the multi-tracked choir of Enos (Eni?) on “Golden Hours”. There are few sharp edges on the album; for the most part, it glides along on Percy Jones’ supple basslines. What friction there is comes from John Cale’s agitated viola lines on “Sky Saw” or Fripp’s dazzling guitar solo on “St Elmo’s Fire”. Occasionally, conventional songs emerge from these sonic landscapes – “I’ll Come Running” is a sweet pop moment – but Eno’s interests lie elsewhere. The album closed with “Spirits Drifting”, whose foreboding minor chords sounded like a dry run for “Warszawa” from Bowie’s Low. Bowie occupied much of Eno’s 1977 – the year of Low and “Heroes” – though he still found time to tinker on December’s Before And After Science. In fact, …Science suffered from a lengthy gestation, with sessions swelling to two years and utilising a shifting retinue of returning players including Manzanera, Wyatt, Fripp, Jones and Phil Collins, Jaki Liebezeit and Dave Mattacks.

Considering Eno’s ongoing experiments with mood compositions, the first half of Before And After Science is a surprisingly lively record. The clipped funk rhythms of “No One Receiving” foreshadow his later work with Talking Heads while “King’s Lead Hat” (an anagram of Talking Heads), references the tight, angular sound of New Wave. After the burnished pop of “Here He Comes”, the album drifts into a deepening state of tranquil repose. The final sequence of “By The River”, “Through Hollow Lands (For Harold Budd)” and “Spider And I” – delicate piano motifs, understated guitar lines, warm choral harmonies – anticipate the next stage of Eno’s career: the ‘ambient’ series. From art rock to African polyrhythms and atmospheric sound textures, Eno travelled at tremendous speed during four short years. Rarely, if ever, did he look backwards. It was as if he had taken counsel from one of his own marvellous Oblique Strategies cards: ‘Trust in the you of now.’

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner