As part of our current Rolling Stones cover story, I interviewed director Brett Morgen about his Stones’ film, Crossfire Hurricane.

I spoke to Brett for about half an hour, but we ended up only using about 300 words from the interview in the issue. The BBC are broadcasting Crossfire Hurricane as part of their Stones’ 50th anniversary celebrations, starting with ‘Part One’ this coming Saturday, November 17. So I figured this was a good enough opportunity to post the full transcript of my interview with Brett…

UNCUT: How did you become involved with the project?

BRETT MORGEN: I was approached by the band via Mick last October, about… I guess at that point, he was interested in making a movie as part of the 50th anniversary festivities. When I first got the call, I assumed they wanted to do a multi-part series like the Beatles anthology. I was told that they were more interested in doing something that felt like a movie, and the only real dictate was they didn’t want it to be a bunch of guys sitting around in armchairs discussing the past. They wanted it to feel cinematic. So the question then became: how do you make a movie about 50 years in two hours? The short of that is, you really can’t. For me what was important at that point was to hone in on a story, and whether that story happened over the course of five years, ten years or 50 years, we would find it. But we didn’t want the film to be Cliff Notes to history. If you’re doing 50 years in two hours, you’re doing a minute a year, or something. I’d been a fan since I was 12 or 13, that’s 30 years now, so I was incredibly intrigued. I also wondered if there was room for a Rolling Stones documentary, and didn’t know what they had in mind. There have been a lot of documentaries about the Stones… actually, let me rephrase that; there have been a lot of documentaries that the Stones have participated in. There haven’t been a lot of documentaries about the Stones story. Meaning, of the 11 or 13 documentaries that the Stones have participated in, almost all of them are either concert films or about a very specific moment in time. There was a TV film they did for the 25th anniversary, 25 x 5, but as far as I know, that was it.

Were you aware of Mick’s reputation before you came on board?

Yes, but a lot of that is coming from the fact, when the press has access to Mick, it’s generally because he’s promoting a project. He has a reputation, which he just said to me, “I was well aware of going into this…” I can’t speak to him, but if he is out to promote in 2012, the interviewer may want to ask him about the Exile recordings, but that’s not what he’s there for. So I walked into this process thinking that Mick would be the most challenging in terms of dredging up the past. In fact, all of his bandmates said that to me. Charlie said, “Oh, Mick’s going to hate this process…” But I actually found that particularly in discussing the early, early years, the origins of the band, he was really animated and excited. We did, I think, 14 interviews together, each one lasting at least two hours. So probably the most extensive interviews he’s done about the past. So we really took our time. At first, we weren’t getting more than a year per session. I think we did three sessions and it took us from 1962 – 65. I found him to be really animated. But when you talk to anyone in any endeavour about their formative years, it is very exciting, it is very innocent, and it’s only later that things become a little more difficult.

What kind of access did the band give you to their archive?

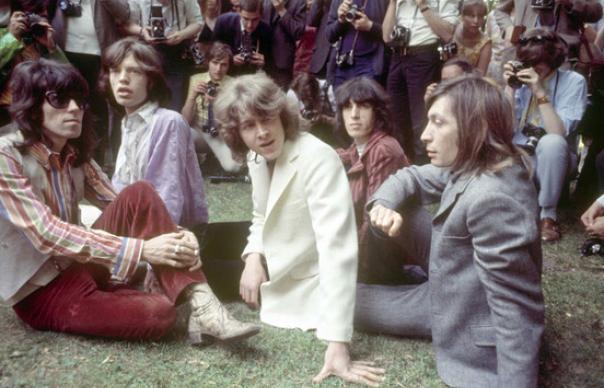

Once we decided we were making a movie, I started to try to get my hands on every element that existed in the period I was going to explore, which was predominantly 1962 – 1981. I felt I could tell a cohesive story during that period, and once I went beyond that a lot of the narrative threads would be disconnected. The story changes after that, so I saw it as a clean break for me. There are so many books written about the Rolling Stones, that I walked into this saying, I don’t want to make an academic history of the Stones, there’s plenty of books that have achieved that, but what I want to do with this movie is that which is unique to cinema – to create a visceral and aural experience, which I think film is most uniquely suited for. That also dictates the story, meaning there are very few discussions in the film about recording sessions, because to me the music is… I don’t want to micro-analyse something that’s ethereal and emotional. I don’t think we mention an album by name, I don’t think we mention the charts; I don’t think we mention singles. It’s more of the story of these five, six, maybe seven gentlemen who were in the Rolling Stones, and how they were launching into the world and how they adapted, over the course of the first 20 years.

When did you start doing the interviews?

The first interview was in January this year, and the last interviews were probably in July. Each of the guys is pretty different. Bill Wyman can talk… he’s somewhat of the band’s historian for the first 35 years of their history, can, is very well renowned for being able to give dates, days, he’s got an encyclopaedic memory of what happened. I probably ended up doing more interviews with Bill than Charlie, who doesn’t really enjoy interviews very much. So each guy required his own thing. Keith is very locked into… I found Keith knows his narrative very well, maybe because he’s written a memoir recently. So each guy required something different. I did two days with Mick Taylor, three days with Charlie, four or five days with Bill, six days with Keith, ten or 14 with Mick.

Were there any specific things you wanted to try and avoid with this film?

There was an overall feeling that we didn’t want this to be the Keith and Mick story. That story has been petty well travelled. And during the period in time that I’m documenting the band, there is an enormous amount of compatibility between them musically. I think that while they had… there were certainly tensions here and there it wasn’t as relevant at that time as it became shortly thereafter.

Is there a lot of unused material?

We did 80 hours of interviews, and there’s probably 60 minutes in the film. It’s always a challenge documenting famous people while they’re alive. The daunting task is that you don’t want to fuck up the Rolling Stones history. I don’t mean you don’t want to get a fact wrong, I mean, you don’t want to make a boring film about the Rolling Stones. Part of the narrative has to do with the fact that those happen to be the years that I listen to them as I was growing up. So I was drawn to it. I had a huge affection for the music I was documenting. But being a fan goes out of the window as soon as you enter the room. I think maybe the first 10 or 15 minutes I was in a room with Mick, I was like ‘Oh, its Mick Jagger.’ But that goes pretty fast. I have a job to do. So hopefully there is a little love and affection underneath everything. But at the same time, I recall saying to Mick when we started, that I’m not a journalist. With a journalist, if a journalist asks a question and Mick doesn’t want to answer it, he could though the journalist out of the room. But I had to have the safety net that I can ask anything I wanted and I was not going to get fired or kicked out of the room or shut down. So there was nothing that was off-limits in terms of what I could ask. But I do think it’s important to be slightly provocative, to push a little bit, because you end up getting some interesting things. But as much as we like to undress out celebrities, or demystify them, that’s not what I wanted to do in two hours. I really felt that this story, it’s 50 years, there’s a lot of people who may have limited knowledge of the band and this was a time to try and get the story of how we became the most dangerous band in the world, where did that come from, why were they sold to the world as the anti-Beatles, how did that affect them, how did that affect the music? That was leading the charge.

Do Mick and Keith address this in the film?

The age-old story is that Andrew Loog Oldham saw the band and decided to market them as the anti-Beatles. As Mick and Keith say in the film, you had to have that in you. Paul McCartney would have had a hard time playing the role that the Rolling Stones did. It was very easy for them to play the bad boys from the get go. I don’t think they realised they were doing it, at the beginning. They would just show up and they weren’t wearing matching outfits, and I don’t think they realised at that moment how scandalous that was. I think they embraced it, certainly in their song writing in terms of the image they were projecting into the world, and then I think it all turns when Mick and Keith get busted at Redlands. What Keith says in the film, which I think is relatively true, is 62, 63, there’s a line in the film when he says, “The Beatles got the white cap, so what was left was the black cap.” Then when we get to Redlands, he says, “Looking back on it, it was more like a grey cap, then after Redlands it was definitely black.” And I think what he was trying to say, was that there was a real innocence to those first three or four years as a scruffy, downtrodden underbelly of society – but really it was because their hard was a 16th of an inch longer than The Beatles. Looking back on it, it’s all silly and innocent. But in part, because they were put out there in that role, it certainly attracted attention from all sides, and part of that was The News Of The World, who decided to use the Stones as the centrepiece of their ‘pop stars and drugs’ exposes, tipped off Scotland Yard who arrested them in February, 1967 at Redlands. At that point, it was not a joke any more. It’s one thing to play the role, it’s another thing to be facing 10 years in prison. As Mick says, this wasn’t just a slap on the hands, there were people who really wanted to send them to jail for really nothing. As they tell you in the movie, they were all on acid that day, and they didn’t even get busted for acid – Keith got busted for having someone smoke pot in his house and was facing 10 years in prison as a result. And I think that not only took their eyes off the prize – meaning, instead of spending all their time in the studio, they’re dealing with lawyers and there’s courtroom stuff – I sensed, this is my own conclusion, that there was a major shift in Mick when that happened. There was more of a mistrust of the media when that happened. They realised they needed to… Keith felt from that moment on the cops were on his tail. In this film, he says, ‘If you want me to be an outlaw, I’ll be a fucking outlaw. I’ll be your fucking Jesse James. I’ve got myself a six shooter.’ It was cowboys and Indians. So then you have this shift in Redlands… where I think that Keith… and a musical shift, of course, where they went from Satanic Majesties to ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’, they really come in to their own musically in a big way coming out of Redlands. They hadn’t been on the charts for 18 months, and they come back and they kill it with ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash” which takes it into a new sound for them. They were never really a hippie band, they were like a Seventies band in the Sixties. It’s got to be a lot more fun to be in the Stones, to be in the band where anything you do you’re celebrated for – no matter how bad or deviant your behaviour it just helps you. Keith told me that John Lennon used to say to him in the early days when The Beatles were a little more buttoned down, ‘I wish I was in your band, it’d be a lot more fun.’ So in a sense, the movie is about these guys who play this role then become this role, then the role almost kills them – it’s a survivors tale, in a way. If one is looking for an arc which is rife with drama, there’s few bands that provide that more than the Stones in the first 20 years of their career, where at any point they could have been derailed but they persevered and that’s what the drama is. I know Mick doesn’t like to talk about this, he’s in it so he can’t look at it this way, so he often says to me things like, ‘You’re the filmmaker, so you have to find these threads that to me that’s not what I was thinking at the time, it’s how you interpret it.’ I think in may ways their story is like a hero myth, that someone is plucked out of obscurity, thrown into the fire, tested, and they come out immortals. They were five guys, ordinary gents, and have to survive battles both external and internal. I think the first four or five years was all of the external battles, meaning the forces of oppression, and the quote unquote establishment, and then later it becomes more of the battles, after Altamont are internal – whether it be their addictions or in-fighting – then they come out the other side and they are truly as close to immortals as you can get.

Did you film the rehearsals in Weehawken, New Jersey?

We filmed the rehearsals in May. It’s not in the movie, unfortunately. I think some of that has to do with the fact the band; they were dubious of me filming rehearsals to begin with. What the Rolling Stones are today, they’re probably the greatest show on the planet, certainly over the last 30 years, and this is where my film ends and the next film begins, so to speak. They become one of the greatest – and they’ve always been great entertainers – but I think the showman in Mick has really blossomed since the Steel Wheels tour. So seeing them in rehearsals is not really the way they feel best represents them. For me, as a fan, it was the single greatest moment of my career.

How did that come about?

What happened was, we were shooting them… I’ve spent all this time with these guys individually interviewing them; I’ve never been in a room with them altogether at this point. So I felt as friendly, whatever… we’re supposed to shoot on a Friday so I needed to scout the day before and we went out to this rehearsal space in Weehawken, New Jersey and it was just… Ronnie, Mick, Keith, Charlie and Chuck on keys and Don Was filling in on bass. There were no managers in the room, there were no assistants in the room, and I went in there so I could see how they were moving around and they went into “All Down The Line”. And I’m literally in the room by myself, three feet from Mick, and I remember thinking to myself, I was so self-conscious, it was one of those moments where you’re like, ‘I want to remember every second of this.’ First of all, they sounded amazing. They hadn’t played together for six or seven years, and so someone would mention the name of a song, someone would say, “Gimme Shelter”, and they would go and throw on the album version or an old live version just to remind themselves of how the song went, and then they would break into it. Literally, in the first run, not having played together in seven years, to my ears it sounded better than I’d ever heard it. They did a “Gimme Shelter” that, having seen all their tours of the last 48 years on film; I’d never experienced anything like it. It was awesome. There are those moments… and then of course you’re sitting there and you’re the only one in the room and you’re like, Should I be dancing? Or is that unprofessional? I don’t want to sit here all professorial, with this certain face on like I’m holding my fingers up to frame a shot or some egghead who doesn’t know how to feel the music. Literally, it hard not to be self-conscious. But I will say the beauty of watching them there is that the essence of the guys is that whatever shit they’re dealing with internally or externally, the music has always been the glue. From my experience, Mick and Keith are as different as any two men I’ve ever met.

How are Mick and Keith currently getting on?

I think musically they get along. They always have, I guess. Listening to, I had access to pretty much all the recording sessions, and listening to how these great songs came to be, and you hear some of that in the film, I think you hear early versions of “No Expectations”, “Prodigal Sun”, “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”, of “Loving Cup”, these are all versions that I’m fairly confident don’t exist on bootlegs that no one’s ever really hard, so I’ve heard all those work up and even from the audio you can hear the camaraderie, compatibility between those guys. It’s hard to articulate, but they share the same ear. It’s not academics here, it’s music, it’s rock and roll and it’s just what sounds good to one person doesn’t sound good to another. Well, with Keith and Mick you have two guys who are completely different from one another who happen to hear with the same ear and really complement each other that way. When I listen to The Beatles, I can always go, ‘That’s a Lennon song, that’s a McCartney song.’ I find that to be much more challenging with the Rolling Stones, to be able to identify this as a Keith song and this as a Mick song. And at the same time, they couldn’t be more different from one another. All the public perceptions of their differences are rather true. They’ve been under the microscope for 50 fucking years so there’s no mystery there, they’re just very different people.