Neil Young is evidently a man who still likes surprises. Patrons at the SLO Brewing Co. in San Luis Obispo, California, found themselves enjoying an unbilled show by Young in April this year. There, he not only unveiled a new album – The Monsanto Years – but a new backing band, too: The Promise Of The Real, fronted by Willie Nelson’s son Lukas, with his brother Micah. Ardent Neil watchers will have already spotted that Young previously played with the Nelsons at last year’s Farm Aid, the Harvest For Hope benefit in Nebraska and the Bridge School event. But despite this influx of new blood, much of The Monsanto Years itself finds Young pursuing familiar goals. Ostensibly, he is championing the ecologically aware message of Greendale, Fork In The Road and “Who’s Gonna Stand Up”, delivered with the urgency of Living With War.

Click here to read Neil Young on the stories behind his greatest songs

The Monsanto Years was recorded in six weeks between January and February at Teatro Studios, a converted movie theatre in Oxnard, California owned by Daniel Lanois. The album’s nine songs share their rough-hewn, country punk qualities with Young’s liveliest studio recordings, while Promise Of The Real resemble a less expansive Crazy Horse. There is, perhaps, an understandable pragmatism on Young’s part in hooking up with these younger players, particularly since Billy Talbot’s stroke and the deaths of Rick Rosas and Tim Drummond last year depleted his pool of regular musicians – the last time Young engaged a group of musicians outside his regular collaborators was with Pearl Jam on 1995’s Mirror Ball: another bunch of eager acolytes sympathetic to Young’s cause.

Click here to read the story of Neil Young’s remarkable year

The result of their endeavours, The Monsanto Years is occasionally rambling, frequently sentimental and sometimes moving. Young opens the rough-and-tumble “New Day For Love” on a positive note – “It’s a new day for the planet/It’s a new day for the sun” – but soon allies himself with those fighting to “keep their lands away from the greedy”. The warm acoustic tones and discrete pedal steel on “Wolf Moon” recall the bucolic charms of Harvest Moon as Young grieves for the “thoughtless blundering” the “seeds of life” endure. “People Want To Hear”, meanwhile, criticises a general lack of engagement with Big Issues like – deep breath – political corruption, environmental disaster, civil liberties violations, world poverty, pesticides and voter apathy. It is a long list, and The Monsanto Years doesn’t entirely benefit from such a broad strokes approach: the album is at its strongest when telescoping in on specifics. Admittedly, Young gets close on “Big Box” – which comes with 8 minutes of thundering Old Black action. The lyrics itself cleave close to “Ordinary People”, Young’s attempt to frame the plight of working Americans against the hostile challenges of living with late-’80s Reaganomics. Here we learn of “main streets boarded up”, “display windows and broken glass/Not a car on the street” and “people working part time at Walmart/Never getting the benefits”.

Click here to read a long interview with Crazy Horse guitarist Poncho Sampedro

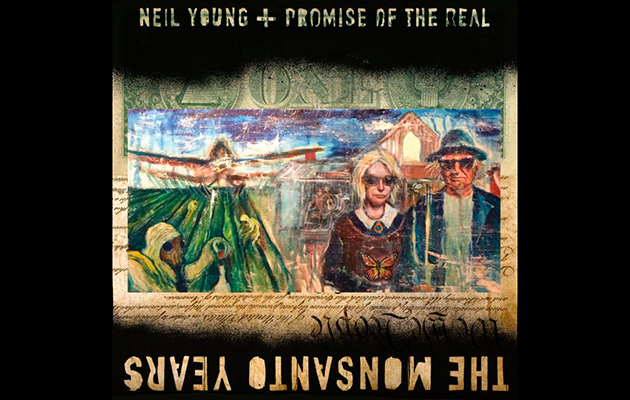

Despite its lighter tone – there is whistling, no less – for “A Rock Star Bucks A Coffee Shop” Young draws our attention to ongoing events in Vermont, where industrial food companies are challenging a legislation requiring the labelling of genetically modified food products. “Mothers want to know what they feed their children”, insists Young. Over a raucous backing track, “Workin’ Man” follows the case of Vernon Bowman, an Indiana farmer who was accused of infringing on Monsanto’s patent for its GM soyabeans. Such social commentary adds immediacy to The Monsanto Years; but Young drops this tenacious approach for the gentler “Rules Of Change”, where he sings wistfully of the “sacred seeds”. Incidentally, the sleeve for The Monsanto Years appears to depict Young and his partner Daryl Hannah as farmers in a psychedelicised take on Grant Wood’s painting American Gothic. Young further aligns himself with the farming community on the title track, which charts the lifecycle of a GM soyabean from soil to store. Grinding away on Old Black, Young laments, “The seeds of life are not what they once were/Mother Nature and God don’t own them any more”. The album closes with the melancholic “If I Don’t Know”, which features some strong free-roaming guitar interplay between himself and the Nelson brothers.

To gauge the strength of Young’s commitment to his cause, it’s instructive to look at where he was this time last year, veering between different projects: ongoing solo acoustic shows, a lo-fi covers album, a new audio system and an impending Crazy Horse tour among them. By comparison, this year seems relatively focused: his intentions clear. Indeed, Young’s message on this album is hardly subtle; after 28 mentions of Monsanto, you suspect he is keen to make his point as simply as possible. “If the melodies stay pretty and the songs are not too long,” he sings on “If I Don’t Know”, “I’ll try and find a way to get them back to you, the earth’s blood”.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

The Monsanto Years is currently streaming on NPR: click here to listen to it

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – goes on sale in the UK on July 9. Click here for more details.

Meanwhile, the August 2015 issue of Uncut is in shops on Tuesday, June 23 – featuring David Byrne, Sly & The Family Stone, BB King and the death of the blues, The Monkees, Neil Young, Merle Haggard and more