Last year, I interviewed the film director Peter Strickland about Berberian Sound Studio, his tribute to the Heath Robinson-style endeavours of analogue sound designers. Strickland and I chatted about the influences for his main character, a tweedy sound engineer called Gilderoy; Strickland mentioned pioneering figures like Adam Bohman, Vernon Elliott and Basil Kirchin. “That whole garden shed thing, which leant towards the dark side sometimes,” he explained. “It’s a very English thing. Like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop characters had this dark streak, alcoholism and so on. If you look at the old tape designs from the period, the actual boxes, the commercial blank tapes, they look like sigils or some kind of pagan symbol, so you can imagine if your eyesight goes a little wonky up late and night looping again and again… you might flip somehow. The weird thing about analogue, it’s a very ritualistic thing. The idea of splicing with razor blades and so on.” Strickland was referring to the earliest version of the Radiophonic Workshop, established in the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios in 1958 by former studio managers Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe. Oram and Briscoe came with a lofty vision, envisaging the Workshop as the British equivalent to the French GRMC, where Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry devised tape-editing techniques in their electroacoustic music studio. Certainly, once it was up and running, the accomplishments of the Workshop were formidable, from sound effects, jingles and music for radio dramas, TV series, educational programming and – of course – their work for Doctor Who. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75V4ClJZME4 True to their questing spirit, many of their most famous achievements were created by surprising means: the sound of the TARDIS materialising and dematerialising was made by running a door key along the bass string of a piano then treating the sound electronically. The score for the 1968 Doctor Who story The Krotons – described to me over the weekend as “the sound of a computer getting wasted” – is full of electronic drones, glitches and bleeps that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Boards Of Canada album. The only surviving original member of the Radiophonic Workshop is Dick Mills, a sprightly 77 years old whose credits run from Quatermass And The Pit to The Goon Show and The Two Ronnies. Mills is currently captaining a live version of the Radiophonic Workshop, whose performance at LEAF, the London Electronic Arts Festival, alongside such luminaries as Giorgio Moroder and New Order is indicative of their pioneering status. Indeed, Paul McCartney, Yoko Ono, Hendrix and Pink Floyd all sought out the Radiophonic Workshop at various times. Mills, dressed in a white lab coat and a sailor’s hat with what look like a pair of early 80s Sony Walkman headphones round his neck, takes centre stage at today’s lunchtime performance. He has the honour of operating the reel-to-reel machine that sits centre stage, a proud reminder of the Workshop’s exploratory roots. Mills’ fellow conspirators are from the Seventies’ incarnation of the Workshop – Roger Limb, Paddy Kingsland, Peter Howell and Mark Ayers, a resilient greyhaired Radiohead slipped through the space time continuum. While Mills operates his beloved reel-to-reel, his colleagues are behind Korg, Roland and Yahama keyboards. There are some who would claim that the day the Workshop took hold of an EMS Synthi 100 modular system was the day they said goodbye to the culture “razor blades and Chinagraph pencils”, as Mills describes it. The magic of the Sixties’ era of ramshackle ingenuity and inquisitiveness, where having “nothing recognisable that could produce music” as Mills remembers it, was replaced by a keyboard. Certainly, there is some distance between the freakbeat electronica of “Ziwzih Ziwzih OO- OO-OO” (written by the Workshop’s most famous alumni, Delia Derbyshire, and “sung” by robots in a Sixties’ anthology series called Out Of The Unknown) and the more conventionally recognisable piece of music they play later from the Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy. It’s apparent in the “Doctor Who Suite”, too, which opens with the original theme and morphs into the Eighties’ version: what once sounded genuinely strange and unsettling became less so once the synths moved in. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jetzY-W78gg But broadly this is a terrific show. Look! Here’s Mark Ayers jamming on an electronic clarinet! Watch Paddy Kingsland and Peter Howell duel on Thermin and voice modulator! Here’s Roger Limb’s fantastic rainbow-striped jumper! There are unexpected moments, too, like "Vespucci", an improbably funky track that sounds like the theme tune to a lost TV series. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7QbmZDG_0B8 These gentleman are craftsmen, working to the highest standards possible. Soak up the wonderful noises and effects created here – strange synthesized ululations, the sound of machines chattering and oscillators firing up. At the end of the performance, a crowd of people make their way to the front of the stage, camera phones on, taking pictures of equipment. A very particular form of worship. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFznOcOOSec Incidentally, the Radiophonic Workshop are playing Rough Trade East on November 25. You can find more details about the event here. There's also two vinyl reissues due, BBC Radiophonic Music and BBC Radiophonic Workshop which come highly recommended. Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.

Last year, I interviewed the film director Peter Strickland about Berberian Sound Studio, his tribute to the Heath Robinson-style endeavours of analogue sound designers. Strickland and I chatted about the influences for his main character, a tweedy sound engineer called Gilderoy; Strickland mentioned pioneering figures like Adam Bohman, Vernon Elliott and Basil Kirchin. “That whole garden shed thing, which leant towards the dark side sometimes,” he explained. “It’s a very English thing. Like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop characters had this dark streak, alcoholism and so on. If you look at the old tape designs from the period, the actual boxes, the commercial blank tapes, they look like sigils or some kind of pagan symbol, so you can imagine if your eyesight goes a little wonky up late and night looping again and again… you might flip somehow. The weird thing about analogue, it’s a very ritualistic thing. The idea of splicing with razor blades and so on.”

Strickland was referring to the earliest version of the Radiophonic Workshop, established in the BBC’s Maida Vale Studios in 1958 by former studio managers Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe. Oram and Briscoe came with a lofty vision, envisaging the Workshop as the British equivalent to the French GRMC, where Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry devised tape-editing techniques in their electroacoustic music studio. Certainly, once it was up and running, the accomplishments of the Workshop were formidable, from sound effects, jingles and music for radio dramas, TV series, educational programming and – of course – their work for Doctor Who.

True to their questing spirit, many of their most famous achievements were created by surprising means: the sound of the TARDIS materialising and dematerialising was made by running a door key along the bass string of a piano then treating the sound electronically. The score for the 1968 Doctor Who story The Krotons – described to me over the weekend as “the sound of a computer getting wasted” – is full of electronic drones, glitches and bleeps that wouldn’t sound out of place on a Boards Of Canada album.

The only surviving original member of the Radiophonic Workshop is Dick Mills, a sprightly 77 years old whose credits run from Quatermass And The Pit to The Goon Show and The Two Ronnies. Mills is currently captaining a live version of the Radiophonic Workshop, whose performance at LEAF, the London Electronic Arts Festival, alongside such luminaries as Giorgio Moroder and New Order is indicative of their pioneering status. Indeed, Paul McCartney, Yoko Ono, Hendrix and Pink Floyd all sought out the Radiophonic Workshop at various times.

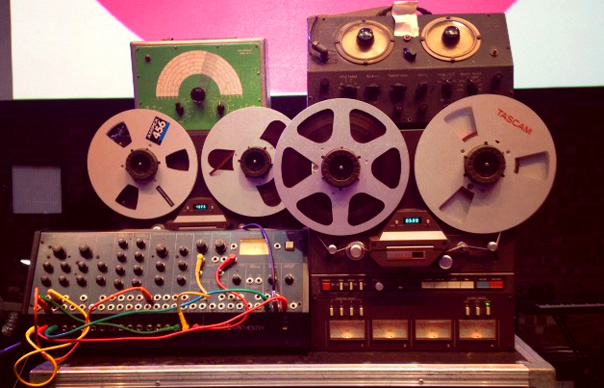

Mills, dressed in a white lab coat and a sailor’s hat with what look like a pair of early 80s Sony Walkman headphones round his neck, takes centre stage at today’s lunchtime performance. He has the honour of operating the reel-to-reel machine that sits centre stage, a proud reminder of the Workshop’s exploratory roots. Mills’ fellow conspirators are from the Seventies’ incarnation of the Workshop – Roger Limb, Paddy Kingsland, Peter Howell and Mark Ayers, a resilient greyhaired Radiohead slipped through the space time continuum. While Mills operates his beloved reel-to-reel, his colleagues are behind Korg, Roland and Yahama keyboards. There are some who would claim that the day the Workshop took hold of an EMS Synthi 100 modular system was the day they said goodbye to the culture “razor blades and Chinagraph pencils”, as Mills describes it. The magic of the Sixties’ era of ramshackle ingenuity and inquisitiveness, where having “nothing recognisable that could produce music” as Mills remembers it, was replaced by a keyboard. Certainly, there is some distance between the freakbeat electronica of “Ziwzih Ziwzih OO- OO-OO” (written by the Workshop’s most famous alumni, Delia Derbyshire, and “sung” by robots in a Sixties’ anthology series called Out Of The Unknown) and the more conventionally recognisable piece of music they play later from the Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy. It’s apparent in the “Doctor Who Suite”, too, which opens with the original theme and morphs into the Eighties’ version: what once sounded genuinely strange and unsettling became less so once the synths moved in.

But broadly this is a terrific show. Look! Here’s Mark Ayers jamming on an electronic clarinet! Watch Paddy Kingsland and Peter Howell duel on Thermin and voice modulator! Here’s Roger Limb’s fantastic rainbow-striped jumper! There are unexpected moments, too, like “Vespucci”, an improbably funky track that sounds like the theme tune to a lost TV series.

These gentleman are craftsmen, working to the highest standards possible. Soak up the wonderful noises and effects created here – strange synthesized ululations, the sound of machines chattering and oscillators firing up. At the end of the performance, a crowd of people make their way to the front of the stage, camera phones on, taking pictures of equipment. A very particular form of worship.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFznOcOOSec

Incidentally, the Radiophonic Workshop are playing Rough Trade East on November 25. You can find more details about the event here. There’s also two vinyl reissues due, BBC Radiophonic Music and BBC Radiophonic Workshop which come highly recommended.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.