About ten years ago, I had a series of conversations with some people preparing a new edition of Harry Smith’s Anthology Of American Music. Their aim, it seemed, was to take the 84 tracks originally compiled from Smith’s collection of 78s, and subject them to a vigorous digital clean-up. How much better would these songs sound, was their reasoning, if all the grit and static was removed, leaving the performances unsullied and sharp? Would songs like Charley Patton’s “Mississippi Boweavil Blues” really sound better without their ancient blanket of fuzz, though? Wasn’t part of the charm of these recordings, memorably classified by Greil Marcus as relics of “the old, weird America”, that they actually sounded both old and weird? Perhaps this is a reason why the reupholstered Anthology was never released. The patina of age is easy and tempting to fetishise, and sometimes it can be used for dubious ends, not least when African-American musicians are patronised for the superficially “primitive” aura of their recordings. But crackle can make the simple act of listening to a song feel like a historical adventure. CDs and MP3s suddenly seem more tactile, less sterile. A frisson of rawness and unmediated authenticity is invested in even the most cynical of commercial endeavours. This, one suspects, is something Neil Young understands very well. In last month’s Uncut, he described the crackle-saturated A Letter Home as “an historic art project”: a collection of songs, by contemporaries like Dylan, Willie Nelson, Bruce Springsteen and Tim Hardin, performed and cut in a 1947 Voice-O-Graph recording booth. The booth is owned by Jack White, no stranger himself to conceptual art projects that take inspiration and mischief from our ideas about authenticity, about how we can tamper with, remake and at the same time still respect musical history. A Letter Home, though, is also part of a larger, all-encompassing project: Neil Young’s ongoing attempt to memorialise and catalogue his own past through a patchwork of new songs, covers, films, autobiographies and upgraded reissues. Sometimes it can all feel like ornery sport, a way for Young to avoid releasing the historical artefact that his fans actually want – the ‘70s motherlode of Archives Volume Two. This latest delaying tactic is very much in the marginalia of Neil Young’s discography, tossed-off by design. The suspicion remains that music, old or new, is not his greatest priority at the moment, falling some way behind the more pressing business of biofuel cars, science fiction novels and, of course, revolutionary new audio players (the key moment in Young’s last Uncut interview came when he cut short a discussion of music and barked, “More Pono questions!”). Nevertheless, this sequel of sorts to Americana is an endearing little document, made more interesting by Young’s decision to render a predominantly ‘60s playlist in a way that would’ve been anachronistically low-fi in the 1940s. “Recorded live to one-track, mono, the album has an inherent warm, primitive feel of a vintage Folkways recording,” the press release trumpets, and the unsteady sonics turn out to complement Young’s wavering voice rather well. Young’s schtick is to use the Voice-O-Graph like a time machine, mapping wild trajectories between eras and dimensions, so that each side of the vinyl edition begins with a hokey “letter home” to his mother in the afterlife, much like the sentimental vinyl missives that were the usual two-minute product of Voice-O-Graph machines. “I’ll be there eventually. Not for a while, though - I still really have a lot of work to do here,” he notes, pointedly. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6H47jI6xanA For the most part, the songs Young chooses are strong enough to withstand the rudimentary treatments. Bert Jansch’s “Needle Of Death”, transparent inspiration for “Ambulance Blues”, is as a consequence the ideal song to use in an exercise about how folk songs are curated and reinvented over time. Wedged into a studio the size of a telephone box with his acoustic guitar and harmonica, the tight focus gives an edge to “Girl From The North Country”, Gordon Lightfoot’s “Early Morning Rain” and “Crazy”. For Side Two, though, the team at Third Man in Nashville dragged a piano over to the Voice-O-Graph, leaving the booth’s door open. And while “Reason To Believe” comes out as odd, poignant honky-tonk, Willie Nelson’s “On The Road Again” and the Everlys’ “I Wonder If I Care As Much” are rickety, front parlour-style singalongs, with Jack White on piano and distant harmonies. It’s a lot of fun, but the prevailing air is one of reflection, and an understanding that – from the 18-year-old Elvis Presley recording “My Happiness” for his mother in a similar machine, to Young’s tremulous take on Springsteen’s “My Hometown” here – cheap novelties can have unexpected emotional valency. Like Tonight’s The Night and many other Neil Young albums, A Letter Home illustrates that vagaries of sound quality can sometimes enhance the drama of a record, and rarely undermine the potency of a good song. How strange, then, that it arrives at a time when so much of Young’s energy is concentrated on promoting Pono. While hyping the ultimate in studio-quality audio players, what else could such a seasoned contrarian do but release the most eloquent argument against their usefulness? Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

About ten years ago, I had a series of conversations with some people preparing a new edition of Harry Smith’s Anthology Of American Music. Their aim, it seemed, was to take the 84 tracks originally compiled from Smith’s collection of 78s, and subject them to a vigorous digital clean-up. How much better would these songs sound, was their reasoning, if all the grit and static was removed, leaving the performances unsullied and sharp?

Would songs like Charley Patton’s “Mississippi Boweavil Blues” really sound better without their ancient blanket of fuzz, though? Wasn’t part of the charm of these recordings, memorably classified by Greil Marcus as relics of “the old, weird America”, that they actually sounded both old and weird? Perhaps this is a reason why the reupholstered Anthology was never released. The patina of age is easy and tempting to fetishise, and sometimes it can be used for dubious ends, not least when African-American musicians are patronised for the superficially “primitive” aura of their recordings. But crackle can make the simple act of listening to a song feel like a historical adventure. CDs and MP3s suddenly seem more tactile, less sterile. A frisson of rawness and unmediated authenticity is invested in even the most cynical of commercial endeavours.

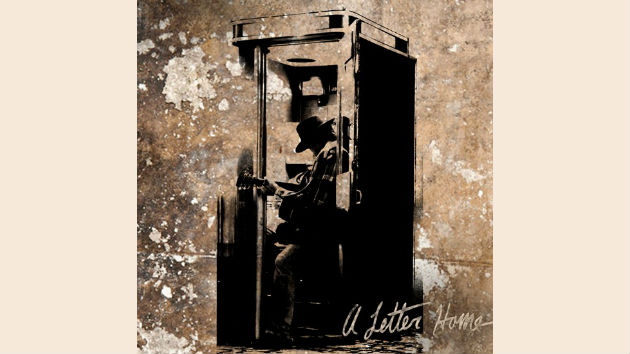

This, one suspects, is something Neil Young understands very well. In last month’s Uncut, he described the crackle-saturated A Letter Home as “an historic art project”: a collection of songs, by contemporaries like Dylan, Willie Nelson, Bruce Springsteen and Tim Hardin, performed and cut in a 1947 Voice-O-Graph recording booth. The booth is owned by Jack White, no stranger himself to conceptual art projects that take inspiration and mischief from our ideas about authenticity, about how we can tamper with, remake and at the same time still respect musical history.

A Letter Home, though, is also part of a larger, all-encompassing project: Neil Young’s ongoing attempt to memorialise and catalogue his own past through a patchwork of new songs, covers, films, autobiographies and upgraded reissues. Sometimes it can all feel like ornery sport, a way for Young to avoid releasing the historical artefact that his fans actually want – the ‘70s motherlode of Archives Volume Two.

This latest delaying tactic is very much in the marginalia of Neil Young’s discography, tossed-off by design. The suspicion remains that music, old or new, is not his greatest priority at the moment, falling some way behind the more pressing business of biofuel cars, science fiction novels and, of course, revolutionary new audio players (the key moment in Young’s last Uncut interview came when he cut short a discussion of music and barked, “More Pono questions!”).

Nevertheless, this sequel of sorts to Americana is an endearing little document, made more interesting by Young’s decision to render a predominantly ‘60s playlist in a way that would’ve been anachronistically low-fi in the 1940s. “Recorded live to one-track, mono, the album has an inherent warm, primitive feel of a vintage Folkways recording,” the press release trumpets, and the unsteady sonics turn out to complement Young’s wavering voice rather well. Young’s schtick is to use the Voice-O-Graph like a time machine, mapping wild trajectories between eras and dimensions, so that each side of the vinyl edition begins with a hokey “letter home” to his mother in the afterlife, much like the sentimental vinyl missives that were the usual two-minute product of Voice-O-Graph machines. “I’ll be there eventually. Not for a while, though – I still really have a lot of work to do here,” he notes, pointedly.

For the most part, the songs Young chooses are strong enough to withstand the rudimentary treatments. Bert Jansch’s “Needle Of Death”, transparent inspiration for “Ambulance Blues”, is as a consequence the ideal song to use in an exercise about how folk songs are curated and reinvented over time. Wedged into a studio the size of a telephone box with his acoustic guitar and harmonica, the tight focus gives an edge to “Girl From The North Country”, Gordon Lightfoot’s “Early Morning Rain” and “Crazy”. For Side Two, though, the team at Third Man in Nashville dragged a piano over to the Voice-O-Graph, leaving the booth’s door open. And while “Reason To Believe” comes out as odd, poignant honky-tonk, Willie Nelson’s “On The Road Again” and the Everlys’ “I Wonder If I Care As Much” are rickety, front parlour-style singalongs, with Jack White on piano and distant harmonies.

It’s a lot of fun, but the prevailing air is one of reflection, and an understanding that – from the 18-year-old Elvis Presley recording “My Happiness” for his mother in a similar machine, to Young’s tremulous take on Springsteen’s “My Hometown” here – cheap novelties can have unexpected emotional valency. Like Tonight’s The Night and many other Neil Young albums, A Letter Home illustrates that vagaries of sound quality can sometimes enhance the drama of a record, and rarely undermine the potency of a good song. How strange, then, that it arrives at a time when so much of Young’s energy is concentrated on promoting Pono. While hyping the ultimate in studio-quality audio players, what else could such a seasoned contrarian do but release the most eloquent argument against their usefulness?

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey