[From the July 2015 issue of Uncut] Southeast of the Texas State Capitol Building is a small four-block street called Jinx Ave. Pulling up to a Wedgewood blue frame house, tucked beneath leafy pecan, ash and mesquite trees, down a path of paving stones, you can’t avoid thinking that it’s far to...

[From the July 2015 issue of Uncut]

Southeast of the Texas State Capitol Building is a small four-block street called Jinx Ave. Pulling up to a Wedgewood blue frame house, tucked beneath leafy pecan, ash and mesquite trees, down a path of paving stones, you can’t avoid thinking that it’s far too apt an address for the 13th Floor Elevators – a band whose genius was thwarted by a string of near-constant bad luck until they dissolved into acid-rock legend. When they fell, they fell from a high altitude, one that seemed impossible to return to.

Yet here in Clockright Studios, as unlikely as it seems, the Elevators – under the auspices of their leader, Roky Erickson – are preparing for a 50th anniversary reunion show at this year’s Austin PsychFest. A long white outer building opens up to reveal a small economical space, panelled in good wood, with oriental rugs, smartly framed posters, and an inner sanctum that holds vintage analogue equipment as well as more recent state-of-the-art gear. The studio is owned by Jason Richards, a member of Erickson’s recent backup band the Hounds Of The Baskerville. It got its name after the power blew out in the studio for a few days: when it came back on, the analogue clock read exactly the right time.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Things like that are common occurrences in the Ericksonian universe. Yet everything seems remarkably normal on this warm spring day. Two of the original band members — Erickson and drummer John Ike Walton – sit under a canvas umbrella sipping sweet tea, shielded from the late afternoon Texas sun. They are accompanied by bassist Ronnie Leatherman, who joined the band in June 1966, straight after graduating from high school.

Together, they wait to begin rehearsal. But one of their number is conspicuously absent. Electric jug player Tommy Hall is still in San Francisco, although he’s assured his fellow bandmates he will be in Texas for the show. He later tells me he has sworn off any inebriants before a show – he only smokes medical marijuana these days since his LSD connection dried up back in 2009. And, pressingly, he has to get a new electric jug. It’s been almost five decades since the founding members shared a stage together; or kept in touch with more than the occasional Christmas card. While Walton and Leatherman live within shouting distance from each other near their hometown of Kerrville, Texas, but they haven’t seen Erickson or Hall in more than 45 years.

Dressed in a black T-shirt, with mirrored sunglasses, jeans and black-and-white Vans embellished with racing stripes, Erickson closes his eyes and leans back in a white wrought-iron lawn chair. His scrupulously clean hands and preternaturally white fingers are stretched across the girth of his stomach like a belt. Breathing deeply, but not asleep, he seems to be conserving power. At this stage of life, it appears he’s figured out what is important to him. And taking things easy is one of them.

“Are you ready to go in there and practice?” his son Jegar asks him, inclining his head toward the studio about 15 feet from where his father is sitting. Erickson opens his milky blue eyes and fixes his son with a look, but doesn’t answer. Instead he turns his head to look at his wife. “Are we having steak for dinner?” he asks Dana, whom he first married in 1974, then again in 2008. “If that’s what you want, honey,” she answers, fussing a little with a strand of hair that has escaped her long black braid. Jegar asks his father again. This time he answers: “We might as well get it over with.”

The 13th Floor Elevators are perhaps rock’s most improbable comeback story. Never mind that it was five decades in coming. But Roky Erickson had a further distance to travel back than most. The prodigious amounts of LSD the band used to imbibe before shows had a profound effect on the frontman. When the Elevators performed at San Antonio’s HemisFair in 1968, Erickson began speaking gibberish on stage. The latest in a long string of similar, equally bizarre incidents, it resulted in the singer being taken to a Houston psychiatric hospital, where he was subjected to electroshock therapy. The band dissolved shortly after. Then, in 1978, guitarist Stacy Sutherland was shot by his estranged wife, Bunni, in a domestic dispute in Houston.

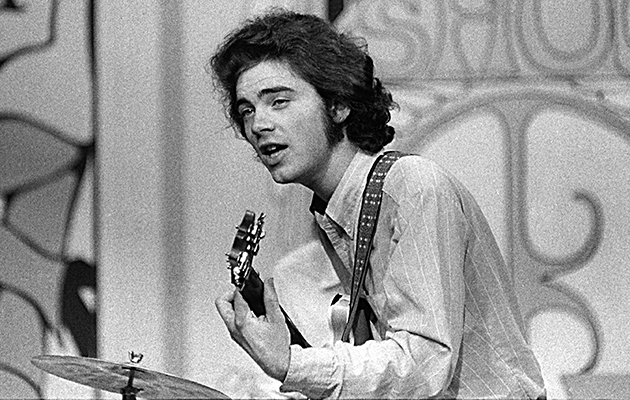

In their heyday, 13th Floor Elevators were bona fide rock stars: a little too good-looking for their own good, a little too dangerous-sounding, their hair a little too long, their pants pegged a little too much, their guitarist a little too brooding. Their debut single “You’re Gonna Miss Me” was a dissolute kiss-off to a love gone bad, with lyrics as beseeching as they were menacing. The song climbed halfway up the charts, landing the Elevators on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand twice in 1966. The song still looms large in Elevators’ lore.

“It is a really great pop song,” explains Patti Smith Band guitarist Lenny Kaye, who included it on his 1972 compilation, Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era, 1965–1968. “That song was the centerpiece of Nuggets. It’s got great hooky chords to start and it’s got that weird middle break with that kind of echo sound from Tommy Hall’s electric jug. I don’t think it has ever been used before or since. And those screams. They may be the best white screams. They’re on a par with Screaming Jay Hawkins.”

Kaye is not the only connoisseur to venerate either “You’re Going To Miss Me” or the Elevators themselves. ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons – whose Houston psych group Moving Sidewalks were contemporaries of the Elevators – confirms the band’s pioneering sensibilities. “Roky and the 13th Floor Elevators were creating something otherworldly,” he explains. “Sound in a scene that had no previous incarnation. Psychedelia!”

The Elevators were brought together by Tommy Hall, a proto-hippie shaman, acid visionary and Texas musician. His plan was to hook up Erickson, then lead singer with The Spades, with another Texas band, the Lingsmen – whose line-up included guitarist Sutherland, drummer Walton, and bassist Benny Thurman. In Erickson, Hall found a voice for his acid revelations. While for his part, Erickson – a former child actor – had already written two songs by the time he was 15: “You’re Gonna Miss Me” and “We Sell Soul”. Founding bassist Benny Thurman explains the origins of the Elevators’ name in suitably Spinal Tappish terms: “Everyone else had only gone to 12. The music was so new that we called it the 13th floor.”

In the sleevenotes accompanying their 1966 debut, The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators, the band advocated the use of LSD as a gateway to a higher state of consciousness. According to Billy Gibbons, they were “creating the vision of being able to go to an undiscovered space. Texas got bigger!”

“No rock band before or since ever delved as deeply into the idea of human consciousness being something that could be expanded into the higher evolution of the species,” says longtime supporter Bill Bentley, who co-ordinated the 1990 Erickson tribute album, Where The Pyramid Meets The Eye. “Tommy Hall worked in the world of psychedelics as a tool to help the progress of humanity. His song lyrics reflected what he learned while under the influence of LSD in a way that turned the band’s best songs, like ‘Slip Inside This House’ and ‘Postures (Leave Your Body Behind)’ into sonic sacraments for their acolytes.”

Almost from the first, Hall insisted that the band members ingest LSD before every show and “play the acid.” At first none of the members balked, embracing the spiritual, mind-expanding properties of the drug, but later there were dark rumblings that if they refused, Hall would sneak the substance into their drinks prior to shows. “The only way I could deal with it was pretend to take it and only take a quarter or half a tab at most instead of the whole,” explains bassist Ronnie Leatherman. Still slender as a boy, with graying hair, a baseball cap and a purple shirt, he has spent the past four decades working for a jewelry company. A perfect amethyst in his left ear will attest to the fact that he knows his gems. “If it was good, I might take some more later, but I really didn’t very often. Tommy was just real insistent, and I was young and wanting to experiment, of course. But we weren’t taking LSD to get blasted. It was spiritual. Stacy was very spiritual. He was a firm believer in God. I don’t have anything against Tommy. He could take all he wanted to. I just didn’t want to. But I don’t regret it a bit. And John Ike took it, but he just didn’t like it. And now he definitely doesn’t, and I wouldn’t ever again, that’s for sure.”

At 72, in his oversized white cowboy hat, Dockers, and striped shirt, John Ike Walton looks more like the manager of a neighborhood hardware store than a rock musician. When pressed, he admits he is reluctant to discuss the Elevators, preferring to save his memories for a book. “I’m tired of giving everything away. But for the record, I want to say, I did not take the LSD,” he huffs, contradicting much of what he has said in interviews over the years. Surprisingly, Erickson is more sanguine about his experiences with LSD. “I never really had a bad acid trip,” he confirms rather matter-of-factly. Admitting to more than 300 psychic excursions, he says, “You have to watch out for the way you view things and think it right. If you respected it, you would have a good trip; if you didn’t, you’d have a bad one.”

Unfortunately, the Elevators‘ existence proved to be a bad trip for the Texas establishment. The band were busted in a televised raid; although most of the charges were subsequently dropped, Hall and Sutherland struggled to find gigs in Texas under the terms of their parole. In 1969, meanwhile, Erickson was busted by the Austin police. In an attempt to avoid a prison sentence, he pled insanity and was sentenced to the Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Austin. There, he was subjected to Thorazine treatments and electroshock therapy. He wrote a book of poetry and befriended a fellow convict, Jimmy Wolcott, an Elevators fan who had murdered his family while high on glue. Critically, Erickson also continued to write songs, forming a band called The Missing Links with his fellow inmates. “I would write these songs on my guitar,” he explains today, as he continues to recline in his lawn chair. “I was writing songs constantly there. I had them stored away in a box.”

++++++

There have been previous attempts to reunite the 13th Floor Elevators stretching back to 1972, when Erickson was finally discharged from Rusk. Did he miss the band?

“Yeah, sometimes I did.”

Did he ever think about putting it back together again?

“Yeah, I thought about it,” he allows. “They wanted us to do a get together of the Elevators when I came back. To regroup the band. It didn’t really work out.”

It’s not clear whether Erickson is entirely concerned with his band’s its 50th anniversary. Does he think their music still holds up today?

“They haven’t played in a long time, but the albums are still out there,” he says a little peevishly, with an odd choice of pronoun, which may prove revealing. “When I was in Philadelphia [actually Pittsburgh, living with his younger brother Sumner after leaving Rusk] I’d listen to the Elevators a little and they’re very exciting. I enjoyed listening to the words. They were talking about metaphysical stuff and things like leaving your body. But I think that’s a hard thing to do.”

So does it feel different being a member of the 13th Floor Elevators in 2015 than it did in 1965?

“Oh, I feel like I have it more down. See, you study, you know certain things,” he says mysteriously. “Things you didn’t know before. I’m studying trying to mingle fiction with existentialism, psychology. That sort of thing. You keep going and you get to where you can identify with what people are trying to teach you.”

Still, there are uncertainties and changes. Tommy Hall is no longer calling the shots from his hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, where he lives on government assistance (and the “thousand a year or so” he claims to earn from Elevators royalties) and watches German television programs all day. More important, there are no drugs any more, save blood-pressure medicine for these 60-somethings. The band have also needed to find a suitable replacement for Sutherland, whose reverb-drenched guitar work was as critical to the band’s sound as Erickson’s unnerving scream and Hall’s electric-jug sorcery. In fact, it’s taking two guitarists: Fred Mitchim and Eli Southard. Southard, who had been playing in the Hounds Of The Baskerville since 2012, observes that Sutherland’s role in the band was crucial, and that the other guys “looked to him for all the cues.

“I really love the records,” he adds. “I wanted to sound as close to the record as I can get but still throw down a genuine-like vibrant performance. I can’t learn all those solos verbatim, mainly because he was just vamping out a lot of it anyway, and it’d kinda go against the spirit of it to just learn what he played that one time verbatim.”

While Southard is talking, Erickson gets up and walks into the air-conditioned studio. The band members — new and old — join him inside, taking their places around their instruments. Erickson settles himself in a chair in the centre of the room, while Walton squeezes in behind his drum kit which is pushed into the far corner. There is an awkward silence while they attempt to get the mics working properly. Jegar Erickson swoops in and swiftly resolves the problem. He removes a roll of black tape out of his pocket, pulls off a piece and puts it over a stray wire in front of his father and then steps back. Without hesitation the band start playing as one – as if they’d been doing this every day for the last 50 years, in fact – “Splash 1”, from their debut album. The song is one of their rare ballads. Southward begins proceedings picking out the song’s minimalist guitar lines before the rest of the band join in. Then Erickson starts singing; he co-wrote the song with Hall’s former wife Clementine, about what happened when the two of them met: “The neon from your eyes is splashing into mine / It’s so familiar in a way I can’t define. If anything, Erickson’s voice is more refined than it was those five decades ago, sounding a bit like the Airplane’s Marty Balin with a bit more tremor, a little more ache. His timing is impeccable, his pitch superb; the rest of the band are impressively tight.

They move quickly on to “(I’ve Got) Levitation,” an out-and-out rocker written by Hall and Sutherland. This version, which barely stretches beyond the two minute mark, is dirty garage rock at its best, as Erickson narrows his odd-shaped eyes and punctuates the song’s breaks with an appropriate “All right” that bring to mind a young Jagger. As soon as it starts, it stops. The silence in the studio is suddenly broken by the piercing scream that kicks off “You’re Gonna Miss Me”. What’s truly odd is that Erickson’s face doesn’t change expression at all when he emits the scream, almost as if it doesn’t come from him. In this version, Erickson comes in behind the beat; it seems slower, more sure-footed, yet more of a lament than the original version. After it closes, Walton takes off his big Texan 10-gallon hat and wipes his brow before they start in on “Roller Coaster”. Based on Hall’s recitation of the acid experience, the song on record is compressed and anxious but today it picks up steam as they play it. There is a palpable sense of tension dissipating when it finishes.

++++++

When Roky Erickson left Rusk Hospital in 1972, it was claimed he had forgotten all the words to the Elevators songs – but he could remember every single Dylan lyric. Six years ago, Erickson admitted to Uncut that was true. Evidently, things have changed in the intervening years. Jegar has assiduously printed off lyric sheets for the songs the band practice during rehearsal, and Erickson hasn’t needed to consult a single one, instead reeling off the words as if he’d written them only yesterday. In a break during the rehearsals, Southard explains that for quite some time, Erickson would regularly perform only two Elevators songs – “Splash 1” and “You’re Gonna Miss Me” during Hounds Of The Baskerville shows. But Southard noticed a change of attitude over the last couple of years.

“We started incorporating a lot of the Elevators tunes into the set, because Roky was really into it,” he reveals “We didn’t really expect that. I don’t know because I wasn’t around, but as I understand it he wasn’t really into playing those tunes with previous bands, for whatever reason. So when we just kind of pitched the idea, ‘Rok, would you want to try playing “Levitation” sometime, or “Fire Engine”? He was, “Well, yeah, I love those songs.’”

Back in Clockright Studios, Walton whoops, “We’re raising hell now!” Erickson nods in agreement. “Yup. It sounds good,” he adds. “Let’s do ‘Reverb’ next.” The song – actually titled “Reverberation” – was a co-write between Hall, Erickson and Sutherland. Thankfully, the lyric “You start to fight against the night that screams inside your mind/When something black, it answers back and grabs you from behind” no longer has the sway over them it once did. “Take it easy with that one,” reminds Erickson, then he says, “Was that four or five?” It transpires that this is code: asking about the time usually signifies that Erickson has had enough. “Want to take a break, Roky?” asks Jegar, who never calls his father “Dad”.

“Nope,” comes the reply. “We can do one more.”

After a little adjustment to his chair, Erickson is ready to go again, tapping his foot even though no music is currently being played. The band ease into “Tried To Hide”, a song Sutherland wrote about burying joints in the sandy beach. Erickson emits soft, approving “Yeahs” during the song. Three minutes later they’re done, which seems to thrill Erickson. “It was good today,” he enthuses. “Nice and easy. That big old cup of hot tea helped.” Although I didn’t see him have one. Yet for all his gnomic aspects, Erickson is clearly the band’s driving force. According to Jason Richards, the studio owner, “Roky is a workhorse. The more we put him to work and the more he sings every day, you’ll watch the rest of us get weary and tired, [but] Roky’s a machine. He just keeps going.”

Southard adds, “He’s got his own set of quirks. It’s not easy to learn them. He always likes to say, ‘Well, you guys are taking it easy on me.’ Which is his way of saying, ‘Please don’t make me play too many songs,’ or ‘Hey, I’m tired.’ I also think he wants it to be cool with everybody. Probably in the past he’s had a lot of contentious relationships with his bandmates. So he’s just like, ‘Let’s all just take it easy.’ He speaks his own kind of weird language, but he’s a lot sharper than I thought he was going to be. He’s really on point most of the time, and he can be the anchor on tour sometimes because he’ll be like, no, no, let’s all calm down. Or when things get tense he’ll make a joke.”

The key, according to Jegar, is not to be careful around him and “have straight conversations with him. He’s very deliberate in what he chooses to say and the messages he wants to put across. But he’s comfortable in his skin and he doesn’t have to overcompensate, so I just found [it’s best to be] really direct and always 100 percent honest, never misleading, because he knows if you’re not telling the full truth. He’s probably at a point where it’s like. ‘If you want to talk to me that way, I’ll respond back to you that way.’”

What’s the best way to communicate with Erickson Snr, then? Jegar considers his answer. “He doesn’t like pussyfoot conversations.” He says eventually. “He wants to be talked to like a dude. That’s what he likes about getting out with the band, now that he knows the band. It’s like, ‘Hey, Rok, how you doing?’ And game on. He likes getting out of the house and hanging out with his brothers and playing some music.”

And, of course, he likes steak.