Consider this the last in a short series of encounters with somewhat cantankerous sorts, following accounts in this space over the couple of weeks of meetings with Lou Reed and Gordon Lightfoot, both of which have stirred some passing interest and lively comment. Today’s subject is Van Morrison, by reputation a notoriously tough assignment, as I would discover. The first time I try to interview him, in his trailer backstage at Knebworth in 1974, it ends badly after he mistakes me for someone who’s written unflatteringly about him and works himself up into a complete and unnecessary strop. Van’s almost pathologically rude, won’t listen to a word of explanation and the upshot is, we end up shouting at each other, loudly enough for people waiting outside to see how things go between us to start looking first worried, then aghast. I eventually storm out of his caravan, slamming a door behind me so hard its hinges nearly pop and the whole thing shakes like a small earthquake’s just hit the area, Van shouting something I don’t quite catch at my retreating back A few years later, I review Morrison at the Self-Aid concert in Dublin, which is headlined by Elvis Costello and U2. Van’s brilliant at the show, at which he previews material from his forthcoming new album, No Teacher, No Guru, No Method. Just before the album comes out, I get a call from an old friend named Kellogs, who I’d first met when he was tour managing the Be Stiff tour (the one on the train). This is June, 1986, by the way. Kellogs now manages Van, I’m surprised to learn. I’m even more surprised when Kellogs tells me Van is doing a day of press – mostly European – to promote the No Teacher. . . album and after being shown by Kellogs the Self-Aid review I’d written for what used to be Melody Maker, Van’s agreed to do it with me. This is both exciting and fairly terrifying news. Whatever, a few days later I’m scuffling nervously outside the door of the Phillipe Suite at the Chesterfield Hotel in central London, waiting to be ushered into the great man’s presence, Kellogs shortly introducing us. I offer my hand in nervous greeting. Van promptly ignores it. “You’ve got 30 minutes,” he says brusquely. “What’s your first question?” My mind of course goes immediately blank and all the finely-honed questions I’d prepared are suddenly vapour. I mumble something about the new album that isn’t on reflection even a question, but which anyway gets Van talking for which I am grateful. “It’s a struggle,” he says of the writing and recording process that even after 20 years he clearly finds difficult. “Always has been. I think when you get past your second album it all becomes something of a routine. So you have to struggle against that, find a way of making what you do sound fresh and new each time. “It’s more difficult now than ever,” he goes on. “I find it difficult to know what to say nowadays, or who I’m saying it to. When I started singing, you know, my audience, they were usually the same age as me and they had at least half the same problems I had. . .but now, I dunno. The 80s are such an extreme period for everybody. As far as what space I’m in, I can’t really find it. I deliberately try not to cater for the commercial market, so I can’t see myself in competition, you know, with second or third generation rock stars. I find myself at this point out on a limb, basically. A lot of people who were writing when I came through originally as a singer-songwriter have disappeared. A lot of them have ended up as MOR entertainers. So it’s kind of left people like myself without an obvious slot, you know. It’s like people don’t quite know what to make of me anymore, he says, shrugging his shoulders, moving uneasily in his chair.” At Self-Aid, he was introduced as a “living legend”, which made him sound like a relic. “I think that’s absolute rubbish,” he seethes. “I don’t feel that way about myself at all. It’s just something these silly little boys in the rock press come up with, this stupid thing about age. I think that’s just part of the mass stupidity that seems to have gripped people at the moment. It’s like, if you’re over 28, you should be singing ballads or you should be dead. It’s ridiculous.” How had he got involved with Self-Aid? “They asked me to do it and I said yeah,” he answers curtly. “See, I kept being asked why I didn’t do Live Aid, right? And the only reason I didn’t do Live Aid was because I wasn’t asked. I figured the next time someone asks me to do something like that, I’ll do it so I don’t have to answer a lot of stupid questions about why I didn’t do it” At Self-Aid, he’d prefaced one new song, “Town Called Paradise”, with this aside: “If Van Morrison was a gunslinger, there’d be a terrible lot of dead copycats out there. . .” “What provoked that?” Morrison snorts when I bring it up. “The constant frustration of people constantly asking me what I think about every Tom, Dick and Harry that’s sorta copied me - and what I think about that is that I’ve had enough of it. I mean, it’s OK if it happens, like, once. After that, after two, three, four albums, when after four albums people are still just ripping me off, it starts to get like a monkey on my back. “And you know, I’m carrying these Paul Brady monkeys and these Bruce Springsteen monkeys and these Bob Seger monkeys, and I’m just fed up with it. I just wish they’d find someone else to copy. In the old days, they’d have called it a form of flattery. But I don’t find it flattering at all. I mean, find someone else to copy, or else send me the royalties, you know.” And what did he think of Springsteen? “Not my scene, you know,” he says dismissively. “I’d rather listen to the source than the imitation. That’s where I’m at.” Was he merely miffed at Springsteen’s huge commercial success? “No,” he says firmly, “not at all. I’m perfectly happy with what I’ve got. At the same time, I don’t see why something I’ve invented, I’ve developed and worked hard to come by should be ripped off, year in and year out, by these people.” We go on to talk at some length about specific tracks on the new album, Van getting himself completely worked up when I ask if “Ivory Tower” is a reply to his critics. He rants almost incomprehensibly about window cleaners and brickies for I don’t know how long and mid-tirade suddenly stops in his tracks, as if he’s got so wound up he’s given himself a stroke. I ask him what the matter is, and why the inexplicable silence, mid-sentence. “Your 30 minutes,” Van says then. “It’s up.” He’s not wearing a watch and there isn’t a clock in the room, but on cue, incredibly, the door opens and Kellogs appears. “Your man there,” Van says, not really looking at me, “will show you out.” And he does.

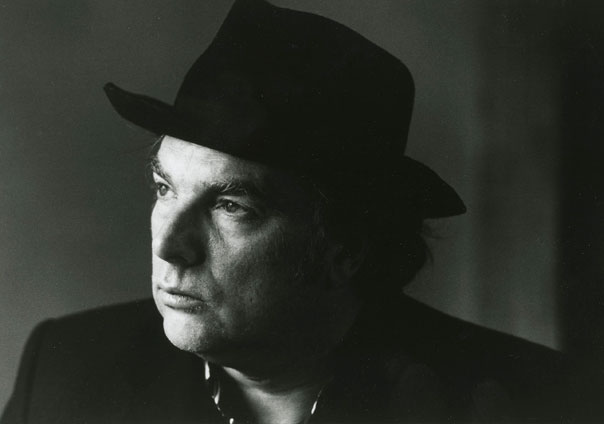

Consider this the last in a short series of encounters with somewhat cantankerous sorts, following accounts in this space over the couple of weeks of meetings with Lou Reed and Gordon Lightfoot, both of which have stirred some passing interest and lively comment. Today’s subject is Van Morrison, by reputation a notoriously tough assignment, as I would discover.

The first time I try to interview him, in his trailer backstage at Knebworth in 1974, it ends badly after he mistakes me for someone who’s written unflatteringly about him and works himself up into a complete and unnecessary strop. Van’s almost pathologically rude, won’t listen to a word of explanation and the upshot is, we end up shouting at each other, loudly enough for people waiting outside to see how things go between us to start looking first worried, then aghast. I eventually storm out of his caravan, slamming a door behind me so hard its hinges nearly pop and the whole thing shakes like a small earthquake’s just hit the area, Van shouting something I don’t quite catch at my retreating back

A few years later, I review Morrison at the Self-Aid concert in Dublin, which is headlined by Elvis Costello and U2. Van’s brilliant at the show, at which he previews material from his forthcoming new album, No Teacher, No Guru, No Method. Just before the album comes out, I get a call from an old friend named Kellogs, who I’d first met when he was tour managing the Be Stiff tour (the one on the train). This is June, 1986, by the way.

Kellogs now manages Van, I’m surprised to learn. I’m even more surprised when Kellogs tells me Van is doing a day of press – mostly European – to promote the No Teacher. . . album and after being shown by Kellogs the Self-Aid review I’d written for what used to be Melody Maker, Van’s agreed to do it with me. This is both exciting and fairly terrifying news.

Whatever, a few days later I’m scuffling nervously outside the door of the Phillipe Suite at the Chesterfield Hotel in central London, waiting to be ushered into the great man’s presence, Kellogs shortly introducing us. I offer my hand in nervous greeting. Van promptly ignores it.

“You’ve got 30 minutes,” he says brusquely. “What’s your first question?”

My mind of course goes immediately blank and all the finely-honed questions I’d prepared are suddenly vapour. I mumble something about the new album that isn’t on reflection even a question, but which anyway gets Van talking for which I am grateful.

“It’s a struggle,” he says of the writing and recording process that even after 20 years he clearly finds difficult. “Always has been. I think when you get past your second album it all becomes something of a routine. So you have to struggle against that, find a way of making what you do sound fresh and new each time.

“It’s more difficult now than ever,” he goes on. “I find it difficult to know what to say nowadays, or who I’m saying it to. When I started singing, you know, my audience, they were usually the same age as me and they had at least half the same problems I had. . .but now, I dunno. The 80s are such an extreme period for everybody. As far as what space I’m in, I can’t really find it. I deliberately try not to cater for the commercial market, so I can’t see myself in competition, you know, with second or third generation rock stars. I find myself at this point out on a limb, basically. A lot of people who were writing when I came through originally as a singer-songwriter have disappeared. A lot of them have ended up as MOR entertainers. So it’s kind of left people like myself without an obvious slot, you know. It’s like people don’t quite know what to make of me anymore, he says, shrugging his shoulders, moving uneasily in his chair.”

At Self-Aid, he was introduced as a “living legend”, which made him sound like a relic.

“I think that’s absolute rubbish,” he seethes. “I don’t feel that way about myself at all. It’s just something these silly little boys in the rock press come up with, this stupid thing about age. I think that’s just part of the mass stupidity that seems to have gripped people at the moment. It’s like, if you’re over 28, you should be singing ballads or you should be dead. It’s ridiculous.”

How had he got involved with Self-Aid?

“They asked me to do it and I said yeah,” he answers curtly. “See, I kept being asked why I didn’t do Live Aid, right? And the only reason I didn’t do Live Aid was because I wasn’t asked. I figured the next time someone asks me to do something like that, I’ll do it so I don’t have to answer a lot of stupid questions about why I didn’t do it”

At Self-Aid, he’d prefaced one new song, “Town Called Paradise”, with this aside: “If Van Morrison was a gunslinger, there’d be a terrible lot of dead copycats out there. . .”

“What provoked that?” Morrison snorts when I bring it up. “The constant frustration of people constantly asking me what I think about every Tom, Dick and Harry that’s sorta copied me – and what I think about that is that I’ve had enough of it. I mean, it’s OK if it happens, like, once. After that, after two, three, four albums, when after four albums people are still just ripping me off, it starts to get like a monkey on my back.

“And you know, I’m carrying these Paul Brady monkeys and these Bruce Springsteen monkeys and these Bob Seger monkeys, and I’m just fed up with it. I just wish they’d find someone else to copy. In the old days, they’d have called it a form of flattery. But I don’t find it flattering at all. I mean, find someone else to copy, or else send me the royalties, you know.”

And what did he think of Springsteen?

“Not my scene, you know,” he says dismissively. “I’d rather listen to the source than the imitation. That’s where I’m at.”

Was he merely miffed at Springsteen’s huge commercial success?

“No,” he says firmly, “not at all. I’m perfectly happy with what I’ve got. At the same time, I don’t see why something I’ve invented, I’ve developed and worked hard to come by should be ripped off, year in and year out, by these people.”

We go on to talk at some length about specific tracks on the new album, Van getting himself completely worked up when I ask if “Ivory Tower” is a reply to his critics. He rants almost incomprehensibly about window cleaners and brickies for I don’t know how long and mid-tirade suddenly stops in his tracks, as if he’s got so wound up he’s given himself a stroke.

I ask him what the matter is, and why the inexplicable silence, mid-sentence.

“Your 30 minutes,” Van says then. “It’s up.”

He’s not wearing a watch and there isn’t a clock in the room, but on cue, incredibly, the door

opens and Kellogs appears.

“Your man there,” Van says, not really looking at me, “will show you out.”

And he does.