Reading a little about the whole Beyoncé lipsynching controversy the other day, I was tangentially reminded of an interview I did with Jim O’Rourke in, I think, 1999 (bear with me…). It was around the time of O’Rourke’s excellent “Eureka”, and we were sat in a Brixton pub, talking about his reluctance to play these scrupulously crafted songs live. His reasons, it turned out, boiled down to the fact that he felt a fraud in some way when he revisited any finished song. If I remember rightly, he wasn’t interested in playing something more than once, privileging spontaneity and improvisation rather than the pantomime of trying to recreate the emotional state and the rough arrangement of the song at its moment of creation. A pretty hardline attitude, clearly, and one that might be admirable more than desirable. Not long after, I saw a duo show with Loren Connors, in which O’Rourke parried audience requests, jerked around for half an hour or so, and didn’t even manage to play much of interest in terms of free improvisation, let alone anything like the chamber pop most of the crowd were demanding. To perform actual finished songs would have been dishonest cheating by O’Rourke’s own restless avant-garde standards. It would have been an inauthentic performance, but most of us there would’ve enjoyed it more. Now, I don’t for one moment believe that Beyoncé Knowles had come to a similar decision when she decided to mime – if that’s what she did; the plot is probably thickening even as I type – at the presidential inauguration earlier in the week. But for most any performer getting on any stage, there’s typically a calculation to be made – subsconsciously, perhaps – about realness, and what that means, and what that means especially to their audience. If Beyoncé was miming, does that make it “an insult not only to her audience but to every singer who ever had to perform The Star-Spangled Banner on stage” (as this piece vigorously argues)? Or is it the work of someone who understands that what most of her audience are interested in are certain powerful signifiers of authenticity, rather than what some people might consider a more ‘real’ performance? Maybe a lot of that audience want to hear her sing the anthem as near perfectly as is possible, and whether she does that on a cold day in DC or in a studio is less important? And maybe the signifiers of authenticity for them are to do with the way they equate certain melismatic flourishes as signs of emotional engagement and commitment, and as a consequence that’s the only kind of ‘realness’ they need? There are more complicated issues at play when the show is a presidential inauguration, of course, where one assumes that it is in the general interest to avoid any overt suspicions of illusion and deception. Nevertheless, the decisions that may or may not have been made by Beyoncé are doubtless very calculated ones, that would’ve factored in the potential repercussions of being found out. This morning I was reading David Foster Wallace’s Rolling Stone essay about being on the campaign trail with John McCain in 2000 (a piece, incidentally, that shows all those complaining music journalists on the Rihanna plane were just experiencing what is commonplace for political hacks). Foster Wallace spends a lot of time trying to work out the difference between a great salesman and a great leader, and which one – or which combination of both – McCain might be. “The only thing you’re certain to feel about John McCain’s campaign,” he decides, “is a very modern and American type of ambivalence, a sort of interior war between your deep need to believe and your deep belief that the need to believe is bullshit.” And maybe this is something like the way plenty of us try and make sense of the music that appeals to us, and why it appeals to us. That Beyoncé’s extraordinary voice has an emotional heft and resonance that might transcend – that might be enhanced by - any trickery that goes on in the vicinity of the mixing desk. That it might be OK even for adventurous musicians like Jim O’Rourke to repeat themselves when they perform. And that the power of so much music from a notional singer-songwriter/folk/roots tradition might not be undermined by a lack of authenticity and realness that its audience often craves, but actually intensified by it. Which is why the infinite yarn-spinning and game-playing and bullshit of Bob Dylan remains so compelling and perhaps magical; that the mystique he has sustained to a greater and lesser extent for 50 years is critical to his art and his appeal, making it so much more effective than the allegedly straight-up confessionals (that are never straight-up confessionals, of course, but something more mediated) of so many songwriters who’ve tried to follow in his wake (his live rethinks of old songs maybe put him closer to O’Rourke’s position, by the by). It’s why I’ll usually be more interested in a performer like Will Oldham and his obtuse fictions, than one like, say Josh T Pearson, who makes such a great play – to some degree disingenuous – out of his own backstory, as if that somehow validates his music and makes it more satisfying. Or one like Gillian Welch, whose understanding of the music she loves, its sense of place and history, is far more important than whether or not she grew up in that place and lived through that history. Or one like Jack White, whose whole career has been an inexhaustible, playful tussle with concepts of realness. I always quote the same thing when I get on this hobbyhorse, but when I first interviewed The White Stripes in 2001, White told me, “I like things to be as honest as possible, even if sometimes they can only be an imitation of honesty. A good impression is interesting if you can’t get the real thing.” What White has subsequently shown is that a “good impression” is usually better than “the real thing”, not least because “the real thing” doesn’t really exist. I spoke with White again last year (the full interview is here), and he recommended a book generally predicated on that idea; Faking It: The Quest For Authenticity In Popular Music by Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor. He also became slightly annoyed with my multiple questions about how he’s screwed around with the truth, not least with regard to his relationship to Meg White. What he didn’t understand, I think, is that I didn’t care whether Meg was his sister or not. What was more fascinating was how and why he chose to manipulate fact and fiction; what compelled him to make those decisions. That trying to unpick the mystery was part of the game, for journalists at least, in much the same way that Beyoncé’s performance has provoked so much delighted hand-wringing and posturing (this piece included, of course). Maybe the truth is that each great artist gives their audience the specific signifiers of authenticity that they need, and, for most people in, well, the real world, everything else is irrelevant? Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

Reading a little about the whole Beyoncé lipsynching controversy the other day, I was tangentially reminded of an interview I did with Jim O’Rourke in, I think, 1999 (bear with me…).

It was around the time of O’Rourke’s excellent “Eureka”, and we were sat in a Brixton pub, talking about his reluctance to play these scrupulously crafted songs live. His reasons, it turned out, boiled down to the fact that he felt a fraud in some way when he revisited any finished song. If I remember rightly, he wasn’t interested in playing something more than once, privileging spontaneity and improvisation rather than the pantomime of trying to recreate the emotional state and the rough arrangement of the song at its moment of creation.

A pretty hardline attitude, clearly, and one that might be admirable more than desirable. Not long after, I saw a duo show with Loren Connors, in which O’Rourke parried audience requests, jerked around for half an hour or so, and didn’t even manage to play much of interest in terms of free improvisation, let alone anything like the chamber pop most of the crowd were demanding. To perform actual finished songs would have been dishonest cheating by O’Rourke’s own restless avant-garde standards. It would have been an inauthentic performance, but most of us there would’ve enjoyed it more.

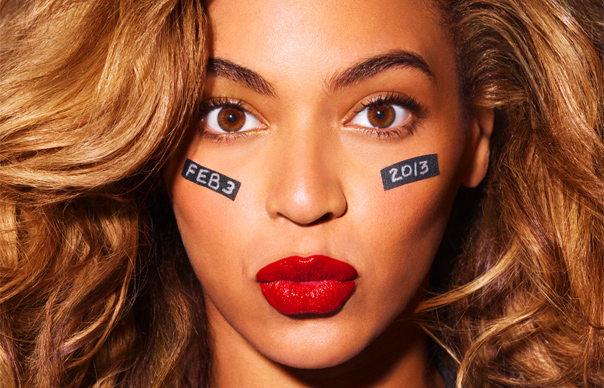

Now, I don’t for one moment believe that Beyoncé Knowles had come to a similar decision when she decided to mime – if that’s what she did; the plot is probably thickening even as I type – at the presidential inauguration earlier in the week. But for most any performer getting on any stage, there’s typically a calculation to be made – subsconsciously, perhaps – about realness, and what that means, and what that means especially to their audience.

If Beyoncé was miming, does that make it “an insult not only to her audience but to every singer who ever had to perform The Star-Spangled Banner on stage” (as this piece vigorously argues)? Or is it the work of someone who understands that what most of her audience are interested in are certain powerful signifiers of authenticity, rather than what some people might consider a more ‘real’ performance? Maybe a lot of that audience want to hear her sing the anthem as near perfectly as is possible, and whether she does that on a cold day in DC or in a studio is less important? And maybe the signifiers of authenticity for them are to do with the way they equate certain melismatic flourishes as signs of emotional engagement and commitment, and as a consequence that’s the only kind of ‘realness’ they need?

There are more complicated issues at play when the show is a presidential inauguration, of course, where one assumes that it is in the general interest to avoid any overt suspicions of illusion and deception. Nevertheless, the decisions that may or may not have been made by Beyoncé are doubtless very calculated ones, that would’ve factored in the potential repercussions of being found out. This morning I was reading David Foster Wallace’s Rolling Stone essay about being on the campaign trail with John McCain in 2000 (a piece, incidentally, that shows all those complaining music journalists on the Rihanna plane were just experiencing what is commonplace for political hacks).

Foster Wallace spends a lot of time trying to work out the difference between a great salesman and a great leader, and which one – or which combination of both – McCain might be. “The only thing you’re certain to feel about John McCain’s campaign,” he decides, “is a very modern and American type of ambivalence, a sort of interior war between your deep need to believe and your deep belief that the need to believe is bullshit.”

And maybe this is something like the way plenty of us try and make sense of the music that appeals to us, and why it appeals to us. That Beyoncé’s extraordinary voice has an emotional heft and resonance that might transcend – that might be enhanced by – any trickery that goes on in the vicinity of the mixing desk. That it might be OK even for adventurous musicians like Jim O’Rourke to repeat themselves when they perform. And that the power of so much music from a notional singer-songwriter/folk/roots tradition might not be undermined by a lack of authenticity and realness that its audience often craves, but actually intensified by it.

Which is why the infinite yarn-spinning and game-playing and bullshit of Bob Dylan remains so compelling and perhaps magical; that the mystique he has sustained to a greater and lesser extent for 50 years is critical to his art and his appeal, making it so much more effective than the allegedly straight-up confessionals (that are never straight-up confessionals, of course, but something more mediated) of so many songwriters who’ve tried to follow in his wake (his live rethinks of old songs maybe put him closer to O’Rourke’s position, by the by). It’s why I’ll usually be more interested in a performer like Will Oldham and his obtuse fictions, than one like, say Josh T Pearson, who makes such a great play – to some degree disingenuous – out of his own backstory, as if that somehow validates his music and makes it more satisfying. Or one like Gillian Welch, whose understanding of the music she loves, its sense of place and history, is far more important than whether or not she grew up in that place and lived through that history.

Or one like Jack White, whose whole career has been an inexhaustible, playful tussle with concepts of realness. I always quote the same thing when I get on this hobbyhorse, but when I first interviewed The White Stripes in 2001, White told me, “I like things to be as honest as possible, even if sometimes they can only be an imitation of honesty. A good impression is interesting if you can’t get the real thing.”

What White has subsequently shown is that a “good impression” is usually better than “the real thing”, not least because “the real thing” doesn’t really exist. I spoke with White again last year (the full interview is here), and he recommended a book generally predicated on that idea; Faking It: The Quest For Authenticity In Popular Music by Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor. He also became slightly annoyed with my multiple questions about how he’s screwed around with the truth, not least with regard to his relationship to Meg White.

What he didn’t understand, I think, is that I didn’t care whether Meg was his sister or not. What was more fascinating was how and why he chose to manipulate fact and fiction; what compelled him to make those decisions. That trying to unpick the mystery was part of the game, for journalists at least, in much the same way that Beyoncé’s performance has provoked so much delighted hand-wringing and posturing (this piece included, of course). Maybe the truth is that each great artist gives their audience the specific signifiers of authenticity that they need, and, for most people in, well, the real world, everything else is irrelevant?

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey