BUY THE LEONARD COHEN ULTIMATE MUSIC GUIDE HERE “It’s just the way it is” It’s been a while now, but mention of 2016 can still prompt an involuntary shudder in music fans. The passing of so many legendary artists and top-class musicians in that year didn’t only prompt sadness and ret...

BUY THE LEONARD COHEN ULTIMATE MUSIC GUIDE HERE

“It’s just the way it is”

It’s been a while now, but mention of 2016 can still prompt an involuntary shudder in music fans. The passing of so many legendary artists and top-class musicians in that year didn’t only prompt sadness and retrospective admiration; on isolated occasions it also led to talk of achieving a kind of perfection.

For some artists, their death came to seem like their latest meticulously planned creative step. David Bowie’s Blackstar album, for example, was released on his 69th birthday – just two days before he died on January 10. The passing later in the year of Leonard Cohen (at 82, though his gravitas made him seem far older) might well be thought of as confronting a finality for which his whole life had been a preparation.

Cohen began life as a poet and novelist, pragmatically became a musician, and – as Richard Williams points out in his review of the posthumous 2019 album Thanks For The Dance, in which Cohen’s final song sketches are spoken softly over a newly tracked backing – ultimately returned to poetry. You might choose to see that as completion of a perfect circle.

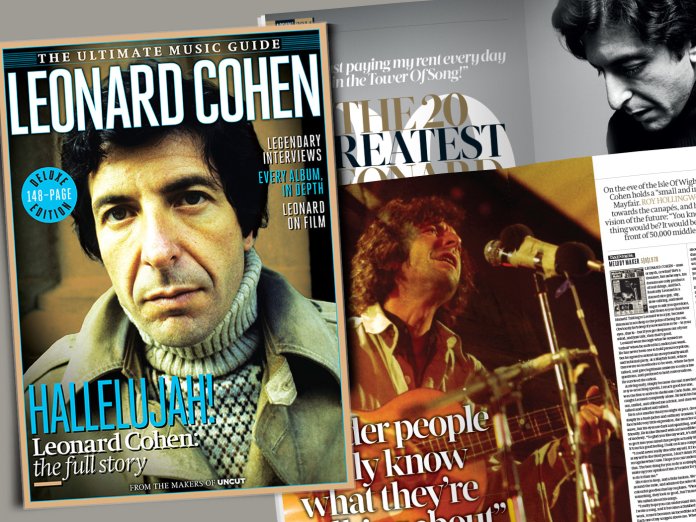

As you’ll read in this Deluxe, 148-page Ultimate Music Guide, what occurred between those points was often turbulent, but Cohen seemed to take it all in his stride. His private life is sometimes portrayed as an eventful itinerary of romances, but was founded on longstanding complex relationships and deep self-questioning, which all found a place in his songs.

Nor were things uneventful professionally. Cohen’s recording life often seemed a battle: a historic conflict between artistic achievement and commercial expectations. One of the features we have added to this new edition is Stephen Troussé’s forensic investigation of Leonard’s tumultuous early 1970s, when he thought he was all washed up – and leading a band, not uncoincidentally, called the Army.

How all this manifested itself in the work, from the self-lacerating Songs Of Love And Hate to the deranged Phil Spector collaboration Death Of A Ladies’ Man you can read about in greater depth in the reviews collected here. What emerges in the longer feature articles, meanwhile, is a picture of a person who made not much attempt to conceal what he was going through (“Make this your last interview,” he says to Roy Hollingworth in 1973, “and let’s quit together”). There were trials, but there were also lessons, however bitter they may have been.

For his fans, Leonard Cohen is a poet, a songwriter, a tunesmith (Bob Dylan particularly praised his melodies). Those who worked closely with him seem more impressed by an artist at the peak of his powers, but who achieved a rare equanimity. Hattie Webb, one of his backing singers, recalled how he behaved during a worrying mid-air incident during Leonard’s 2008 tour.

“All the people around me were very frightened,” she recalled. “I was gripping hold of my drink and seeing my life flashing before my eyes, and I looked over at Leonard. He was completely and utterly calm, and said: ‘Don’t worry, darling, nothing can happen to you – it’s just the way it is.’ That’s what we take from Leonard. He worries about the small things and deals with those. And with the big things, he lets nature take its course.”

Enjoy the magazine.

Buy a copy of the magazine here. Missed one in the series? Bundles are available at the same location…