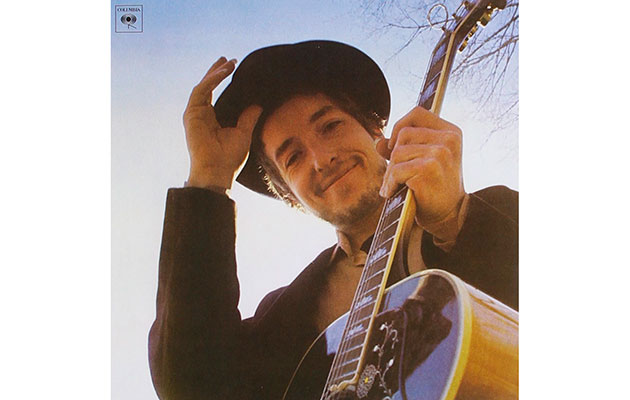

Some of Johnston’s key recordings – say Dylan’s Nashville Skyline – are indeed remarkable for their documentary veracity (vis, “…is it rolling, Bob?”). But staying out of the way doesn’t remotely cover the subtle placing of musicians together in environments, the ear for arrangement, and behind the scenes horse-fixing that goes into a Johnston recording. His emphatic fulfillment of the producer’s brief is a character game.

“When I first went in there for Highway 61,” he says, “I found a piece of paper on the floor. I said to Dylan, “What’s this?” and he said. ‘It’s something Al Kooper wrote down, it’s overdubs.’ I said, ‘If you keep doing that there won’t be anything left.’ ‘I’m gonna cut live. If we have to overdub, we’ll overdub. But not because Al Kooper wants 14 chances to be a little better.’”

Highway 61 was the last Dylan record that Johnston recorded in New York until he returned for New Morning in 1970. He had done impressive work there, but this was not his city. His natural environment was a place where his recording and business reputation still endures, a conservative town then in need of a shake-up.

“I was surprised Dylan came to Nashville,” says Charlie McCoy. “I’m not sure he was too keen on the idea – but I think Johnston used that session in New York as a way to have him convinced. Like, ‘Did you see how easy that was? That is how it would be in Nashville…’ Knowing Bob, I bet he was selling it bigtime.”

“I didn’t get him down there,” says Johnston today of Dylan’s appearance in Nashville. “You couldn’t make him do anything.”

Still, Bob Dylan’s arrival to record in Nashville in February 1966 conferred on Bob Johnston a role as change agent in the city: musically, culturally, even structurally. For him, the fabric of Columbia’s Studio A came to embody the intransigent attitudes to making music in the city.

“In Nashville they had little rooms,” he says of the isolation booths in the facility. “It looked like a toilet, with wooden earphones and one little lightbulb. You couldn’t hear what the other musicians were playing.

“So the next day, I took all that out,” he continues. “I had someone burn it all. I put Dylan in a glass booth so they could see him and play together – that’s how that music started, not in six little rooms.”

What he had done with Studio A (it wasn’t quite the sacrilegious act it sounds – Columbia’s Studio B, Owen Bradley’s original “Quonset Hut” was the home of most historic recordings in the city) Johnston and Dylan now did with Nashville’s traditional timetable.

“We were used to doing three or four songs in a three hour session,” says Charlie McCoy. “So when Dylan came in that first day and said, ‘I’m not finished writing yet’ and we didn’t start recording til 4am – that was a shock to us. But we were on the big clock, so it wasn’t all that bad!”