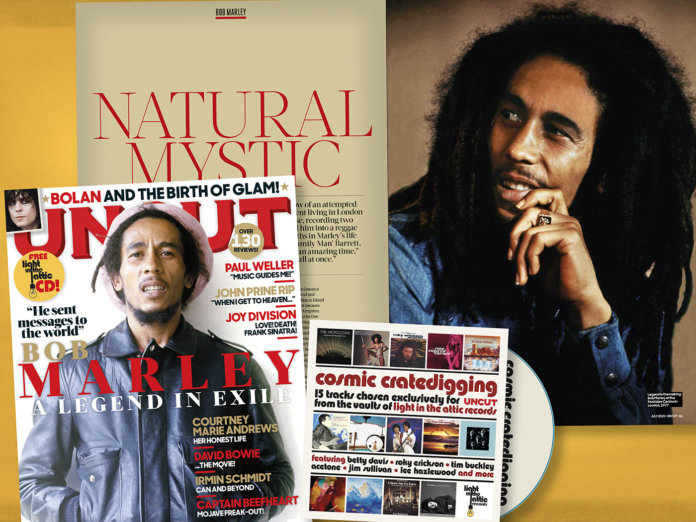

The new issue of Uncut – in shops now or available to buy online by clicking here – features a fascinating and comprehensive account of Bob Marley’s 1977, the year he spent in exile in London creating his landmark albums Exodus and Kaya. In it, Graeme Thomson revisits a whirlwind 12 months in Marley’s life with help from Chris Blackwell, Marcia Griffiths, Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett, Don Letts, Junior Marvin and other eyewitnesses.

Marley arrived in London in early January 1977, shortly before turning 32, following the most tumultuous few weeks of his life. On December 3, two days before he had been due to perform at the Smile Jamaica concert, seven gunmen entered his compound at 56 Hope Road in Kingston. Marley was shot in the chest and the arm but escaped without serious injury. His wife, Rita, was shot in the head, though miraculously she made a full recovery, while his manager, Don Taylor, was struck in the legs and body.

“He didn’t talk about the shooting much, but he was very upset that people would come to shoot him,” says Chris Blackwell. “Bob wasn’t at all someone who was boastful or thought he was the greatest thing ever – he was a very natural person – but I think he was shocked that people would want to shoot him, and it took him a while to work through that.”

The reggae superstar had chosen to deal with the fallout from the shooting in London, where his recent brush with mortality infused his life and music with a new sense of purpose. On the one hand, it was business as usual. “Bob set up his Rasta camp here,” says Don Letts, at the time a budding DJ, entrepreneur and “baby dread” who was befriended by Marley. “It was like he had picked up a bit of Kingston and transplanted it to Chelsea.”

The cultural exchange worked both ways, however. In London, Marley integrated with young punks and Rastas, visited West End nightclubs and dingy shebeens, played football in his local park, recorded with his wife, conceived a son with his girlfriend, and fell prey to the injury that eventually led to his death four years later. “It was an amazing time,” says Marcia Griffiths, a member of his vocal group, The I-Threes. “Everything was happening all at once.”

The duality of Marley’s year in exile is most clearly reflected in the music he created during that time. In London he made two albums, Exodus and Kaya, in a matter of months. They feature some of his deepest and most spiritually resonant music, from the lowering “Natural Mystic” to the declamatory “Exodus”. Yet it was also the year in which Marley recorded the songs that transformed him from a roots reggae star to a pop pin-up. “Three Little Birds”, “One Love”, “Jamming”, “Waiting In Vain” and “Is This Love?” were all released during this remarkably fertile period. “He was sending messages to the world,” says Griffiths. “Those two albums cover everything.”

At the heart of it all is Exodus, perhaps Marley’s most ambitious and universal statement. “It was very advanced, very progressive – almost futuristic,” says his eldest son Ziggy, who remastered the album in 2017. “Exodus took reggae to the next level in terms of instrumentation, beats and musicianship. It made reggae a more international and accessible thing, with elements people could relate to in their world.” Blackwell puts it more succinctly: “Exodus was a huge record for Island – and a revolutionary record for reggae.”

You can read much more about Bob Marley’s year in exile in the July 2020 issue of Uncut, out now.