Originally published in Uncut's February 2022 issue “What I miss most about Moebi,” explains Hans-Joachim Roedelius, “is his weird kind of humour. Our partnership was very special, and based on the same roots as my solo work: curiosity, interest, friendship, love.” ORDER NOW: Bob Dyl...

Originally published in Uncut’s February 2022 issue

“What I miss most about Moebi,” explains Hans-Joachim Roedelius, “is his weird kind of humour. Our partnership was very special, and based on the same roots as my solo work: curiosity, interest, friendship, love.”

Across 40 years, multiple albums and collaborations with the likes of Michael Rother, Conrad Schnitzler and Brian Eno, Roedelius and his creative partner Dieter Moebius crafted the music of Cluster and helped define the sound and aesthetic of kosmische synth music. Moebius passed away in 2015, but Roedelius, now 87 and still prolifically composing and releasing music, is the eager guardian of the duo’s legacy, answering Uncut’s questions from his home in Austria. “The last year or so has been rather exhausting because of all the bad and difficult circumstances within the Covid situation – but it has been very interesting working on music with [American collaborator] Tim Story from both sides of the ocean.”

Whatever the outside circumstances, the gentle channelling of inspiration “out of the belly” has been Roedelius and Cluster’s long mission. “Thought is only to control the whole process,” he explains. “I see my work as one long continuous thread, and it will continue until I have to leave the soil of this planet.”

TOM PINNOCK

_____________

KLUSTER

KLOPFZEICHEN

SCHWANN AMS STUDIO, 1971

The debut, created as a trio with Conrad Schnitzler, their music overlaid with various religious texts

HANS-JOACHIM ROEDELIUS: My musical experience started with me as a bush-drummer in the macchia of Corsica, when I lived there for some time. At the beginning, I got in a trance hitting an old iron oil barrel around midnight, ending with bloody fingers in the morning. There were no drugs at all, not even alcohol, just heavy interest and fun. Then I got involved in free improvisation in Berlin in the late ’60s and we went along this way until Conrad Schnitzler left Kluster, and Moebius and I continued in the same experimental way as Cluster. Did we have a strong bond from the start? Well, it was an adventurous journey from the first moment, because we wanted to do what was impossible to know in detail at the beginning. I was a physiotherapist and masseur and Moebius was a graphic designer, and we were very curious whether we would be able to become real musicians and artists. The situation in Berlin and the foundation of the [experimental arts club] Zodiak at the time was the best way to find out whether it would work and what it would bring us as human beings and artists in regards to awareness, consciousness, understanding. This album was our entrance into it all. The recording process consisted of sitting down, hitting a first key and waiting how it developed by ‘itself’. It was the first real production with Conny Plank in his studio in Godorf near Cologne. The spoken texts occurred after a priest heard us performing. Kluster just sat down there trying to create relevant soundscapes that pleased our ears, Conny recorded it and the composer Oskar Gottlieb Blarr listened through to find out what he liked as background for the text or poetry from the chosen artists of the ecumenic movement.

_____________

CLUSTER

CLUSTER 71

PHILIPS, 1971

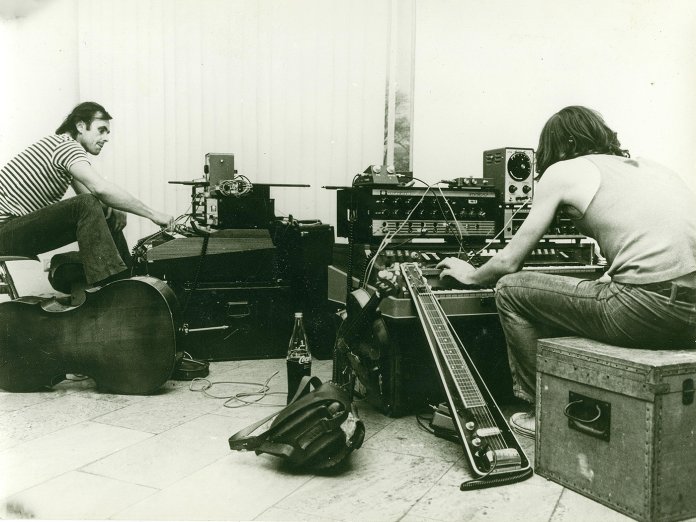

With Schnitzler departed, Conny Plank becomes the third, silent member of the renamed Cluster

This was recorded in Hamburg’s Starmusik Studio. I don’t recall much about it, only that we had great fun and were totally satisfied with the result, because it was our first real studio work. We had no synthesisers as such in the beginning – instead we used guitar, cello, keyboards, tone generators and little handmade electronic toys from our side, and then Conny was well aware at the time of the specifics of his grand studio mixer, as the artist that he was. We did a very collaborative job. Our interest in improvisation came purely from curiosity. There was no other way than practising it with whatever instrument or equipment we had to become aware whether we could do it and how. It was pure curiosity, just our interest in which way a piece developed by ‘itself’. The tracks on here are untitled, yes – we just didn’t want to give names to it at the beginning, perhaps because we thought that music evokes its own strengths and emotions. Did this album lay the groundwork for everything that came after? Of course.

_____________

CLUSTER

CLUSTER II

BRAIN, 1972

Six stunning pieces, less industrial and more melodic, with “Im Süden” prompting Michael Rother to suggest a collaboration between Cluster and Neu! – instead, Cluster and Rother formed Harmonia the following year

This feels like a breakthrough? Well, we were just getting more into it, and getting more experienced at being able to elaborate it. Conny was working with us again – as well as being a multi-talented artist, he was a very experienced sound master and great human being. He contributed as a fellow musician, adding sounds with his mixing table such as reverb, delay and other effects enriching the whole pieces so that they finally became somehow unique. I don’t remember much about the sessions, which were again at Hamburg’s Star Studio, but we were happy being allowed to try to work there the way we wanted to. It was a normal studio, so not as special as Conny’s studio later on, but it helped us a lot to open the doors to new sonic territories. Moebi and I interacted as a duo during the recordings in the same way we played live, it was usually a sort of Q&A.

_____________

CLUSTER

ZUCKERZEIT

BRAIN, 1974

With Rother on production duties, Roedelius and Moebius each created five solo tracks and pieced them together to create this up-tempo, beat-driven record

Moebi and I decided to work separately on this album, because we wanted to see what we would bring if we showed up individually. Michael Rother is listed as producer, yes, but what did that entail? Well, he provided some of his machinery that we used. We weren’t trying to create a ‘pop’ album, even though there are short track lengths, it was just another step on our way to learn how to create relevant music out of the moment. We were living in Forst [a rural community by the river Weser in Lower Saxony] by this point. When I moved with Moebius there, it seemed at first to be like paradise – dangerously idyllic! But we didn’t know that a plant up-river was broken and kids were dying nearby and down-river. In our community in Forst three people, one kid and two adults, died. As soon as we got to know about this fact, my family and I left Forst, but for some years it was our paradise, after travelling so much and having no real place to stay in peace and relax.

_____________

***UNCUT CLASSIC***

CLUSTER

SOWIESOSO

SKY, 1976

The ultimate kosmische album, Cluster’s fourth album bottles the essence of their rural home with its relaxing, quasi-ambient textures

It wasn’t our plan to capture the mood of Forst and the countryside – no intention, just reflection. But the influence came from the beauty of the place at Forst, of course, and the happiness to have been able to settle down after so many years of travelling. On a personal level, I had got together with my wife, and our first child was born in a homebirth in front of an open fireplace there. The sessions for Sowiesoso just happened when Moebi and I felt relaxed enough after a hard day’s work to go down to Harmonia’s studio. Were we collaborating fully again? I think so. And working in Harmonia with Michael Rother had definitely changed Cluster’s music – for sure, it had influenced us to take Cluster in a more harmonic direction. How were these tracks developed? Mostly in the Cluster way and direction – as I said before, out of the belly, that is the Cluster way.

_____________

CLUSTER & ENO

CLUSTER & ENO

SKY, 1977

The duo’s first collaboration with Brian Eno, also featuring appearances from Can’s Holger Czukay and synthesist Asmus Tietchens

What drew us and Eno together? A friendship that had started a long time before we finally worked together. We had met Eno two years earlier at a concert in Hamburg, and had come to like him because of his friendly nature and his companionship, and appreciated him because of his sensitive jamming with us at one of our concerts, and we invited him to join us in Forst for a joint production. Because we had many daily tasks in our quasi-commune in Forst – for example, gathering firewood from the forest for the winter, taking care of our recently born child, tending the garden – Eno, who would have rather spent all day in the studio, agreed to help with some work, but apart from occasionally carrying around our baby Rosa, he didn’t really do much. But he found how we mastered our life in Forst appealing, how we made music together. We recorded with him as Harmonia, which was released decades later [as 1997’s Tracks & Traces]. [We then made] music as Cluster with him at Conny Plank’s about a year after his visit to Forst. We shared curiosity, an eagerness to experiment, love for nature and love for people. The song “By This River” [released on Eno’s Before And After Science, 1977] became one of Brian’s most famous songs – I wrote the basic music, Brian the melody and words.

_____________

CLUSTER

CURIOSUM

SKY, 1981

The final album before Cluster’s decade-long break, a bizarre but compelling experiment in cartoonish, absurd synths and electronics

We recorded this on a four-track machine in a monastery in the north of Austria. It was, though it might now have changed, an old building in the midst of a big forest. The owner gave it to artists to stay and work there as long as needed – what a splendid gift! A normal studio in a city is something, but doing ‘it’ in places like this monastery, for example, makes it special. It was inspiring to be in this religious environment, of course, we never denied to be religious. I don’t remember us having any new gear for this. We always were Cluster as character and trademark, two guys together in a deep friendship on their own way in life. I have lived in Austria for many years now; my Austrian-born wife got me there, but I believe [my destiny to live there] was already fixed hundreds of years ago by my ancestors. One of them, preacher and cantor Johann Christian Roedelius, was a contemporary of the godfather of classical music, Johann Sebastian Bach, and the two of them played the same organ in St Thomas Church in Leipzig.

_____________

CLUSTER

ONE HOUR

PRUDENCE/MÚSICA SECRETA, 1994

The second album produced from Cluster’s reunion, an ambitious hour-long soundscape

Why did we decide to get back together for [1991’s] Apropos Cluster and this album? Cluster is Cluster is Cluster is Cluster is Cluster ad infinitum. The story is that this album came from hours of improvisation, but it didn’t come from ‘hours’, it came from one hour. We used two keyboards, tone-generators, self-made little electric toys, a knee-viola, a cello and a guitar. What were we listening to at the time? I remember Hapshash And The Coloured Coat, Captain Beefheart and Jimi Hendrix. But certainly Cluster is always unmistakeable, at least to my ears. Did Moebi and I disagree much over the years? As we began in 1969 to stay and work with each other, there was of course an expiration date for something that was so unique and extra at the time as Cluster or Kluster. The creative air was running out after more than 40 years. It was a normal process of getting tired doing always the same thing.

_____________

CLUSTER

QUA

NEPENTHE/KLANGBAD, 2009

The final album by the duo, 17 assorted miniatures and epics recorded in Maumee, Ohio

This is Cluster’s swansong, the most relevant contemporary electronic music of all time ever. This was recorded in Ohio in Tim Story’s studio, it was another station in the Cluster journey, and in Tim we had another silent member of the group once again. He is the grandmaster of sound design – a Grammy nominee once for his music for The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow narrated by Glenn Close. How had the spark and musical connection between Moebi and me changed? We were flexible all the time, we did what we did with no other purpose than ‘we want to do what we want to do what we want to do’ out of the moment, and fortunately we were able to. As long as one is able to keep his interests fresh, to stay authentic from the beginning, to show up with understanding and love, why shouldn’t he be loved and appreciated by his audience forever?