"My complete being is within those three albums." Rob Hughes and Stephen Dalton uncover the complete story of Bowie's life-saving escape to Berlin. How he turned Iggy Pop into a health freak, embraced Brian Eno's "oblique strategies", documented Tony Visconti's indiscretions, and made a fearless and...

By late 1977, Bowie’s globe-trotting curiosity was back to full strength. In the autumn he holidayed in Spain with Bianca Jagger and in Kenya with his young son, Joe (Duncan Jones). In November he flew to New York to narrate a version of Peter And The Wolf with the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra, ostensibly as a “present” for Joe. He was no longer a mere rock star, but a painter, actor, composer and “generalist” of the arts. Beneath its monochrome gravitas and jabbering hysteria, “Heroes” tells a tale of redemption and recovery.

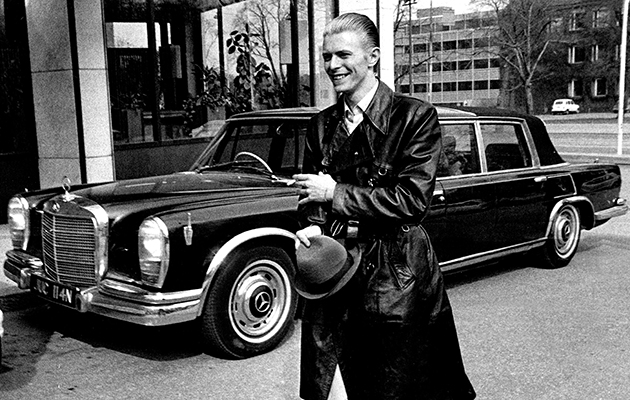

The new year began with yet more drama for Bowie. In early January 1978, his estranged wife Angie ended up in hospital after a couple of apparent suicide attempts. At the time, Bowie was in Berlin, shooting Just A Gigolo with director David Hemmings.

Hemmings had flown to Switzerland just before Christmas to persuade Bowie to star as Paul, an emotionally numb ex-soldier who becomes a gigolo in Berlin during Hitler’s rise. Intended as a black comedy, the film was released to widespread hostility a year later. Most reviewers singled out Bowie’s wooden performance for special punishment.

“They missed the point,” sighs Hemmings. “The point about that character is that he’s a sponge – he’s supposed to be cold and somewhat thick. You don’t get Ziggy Stardust if you want to see someone playing a German soldier who survived the war. That’s called acting.”

Bowie himself later disowned the film, dismissing it as “my thirty-two Elvis Presley movies contained in one”. Hemmings calls this judgement “massively unfair, and it does down himself, me and the film far more than it deserved. David thinks we didn’t take it seriously enough, but that’s not my directorial style. If we had taken it seriously, it would have been a very depressing shoot indeed.”

After the shoot, Bowie took another safari with his son, before starting rehearsals for the Stage extravaganza, his most ambitious world tour to date. It would bring Low and “Heroes” alive for the first time, as well as coating half of Ziggy Stardust in a shiny varnish of New Wave modernism.

Alongside stalwart sidemen Alomar, Davis and Murray, Bowie recruited new players, including twenty-eight-year-old Kentucky-born guitarist Adrian Belew. On Eno’s recommendation, Bowie poached Belew from Frank Zappa’s band during one of Frank’s own interminable guitar solos at a Berlin show. Spotting Bowie and Iggy over by the monitors, Belew strolled over for a surreptitious chat. “Later that night,” says Belew, “we tried real hard to sneak off and have a private talk, but inadvertently ended up in the same restaurant where Frank and some of the band were at. The jig was up. David tried to talk to Frank, but Frank wouldn’t have anything to do with him. He kept calling him ‘Captain Tom’. It was an ugly scene, really.”

Eventually, Belew got Zappa’s blessing and headed off to rehearsals in Dallas in March. Gathered at a hotel on the edge of town, the band crowded into Bowie’s room one night to watch Beatles spoof The Rutles. Kicking off in San Diego on March 29, Stage was a juggernaut which toured the globe for six months in ’78 filling arenas of twenty thousand people and more. With its neon backdrop and space-age jumpsuits, it received hugely positive reviews but translated into an oddly muted double live album, released in September.

The tour’s European leg ended with three shows at Earl’s Court in July, two of which were filmed by David Hemmings for a proposed movie. “We shot it with about ten cameras over two nights,” Hemmings recalls. “We put it all together in Majorca, where I had a house, and David came to stay. But at the end of it he didn’t like the cut, so he never released it.” Bowie confirms, “I simply didn’t like the way it had been shot. Now, of course, it looks pretty good and I suspect it would make it out some time in the future.”

In September, Bowie and most of the Stage band took a break from touring to begin work on the last of the Berlin/Eno trilogy. Like Low, Lodger was not actually recorded in Berlin. Instead, it was started at Mountain Studios in Montreux, and eventually finished at New York’s Record Plant in March 1979.

Originally titled Planned Accidents, Lodger was constructed using more self-consciously disruptive methods than Low or “Heroes”, resulting in a kind of Dadaist collage effect. “It was a lot more mischievous,” says Bowie of the third Eno instalment. “Brian and I did play a number of ‘art pranks’ on the band. They really didn’t go down too well. Especially with Carlos, who tends to be quite ‘grand’… ”

Lodger overturned the monolithic minimalism of Low and “Heroes” with a cluttered pile-up of ethnic funk, sampled static and jarring musique concrète. In many ways, it was more experimental than its two siblings, but it lacked the emotional kick of either. A case could be argued that this is Bowie’s lost classic, but its listless mood and muddy sound are undeniable flaws.

“I think Tony and I would both agree that we didn’t take enough care mixing,” says Bowie. “This had a lot to do with my being distracted by personal events and I think Tony lost heart a little as it never came together as easily as Low and “Heroes” had. I’d still maintain, though, that there are a number of really important ideas on Lodger.”

Visconti calls it “a strange album, dark and light”, made in “two uncomfortable studios” at a time when “cocaine was ubiquitous and naively abused”.

Released soon after the critically savaged Just A Gigolo, in May ’79, Lodger was not well reviewed. RCA tried to pitch it as Bowie’s Sgt. Pepper, but Rolling Stone called it “a footnote to “Heroes”, an act of marking time”, while NME sniffed that Bowie was “ready for religion”.

Smartly drifting away from pure electronica just as synth-pop copycats flooded the UK charts, Lodger predicted a decade of Western pop flirtation with multi-cultural flavours. But it also alienated die-hard fans hoping for Bowie’s next bulletin from the depths of Teutonic despair. Siouxsie Sioux calls Lodger “the first of many to disappoint”, while Stephen Morris says, “It’s crap, everyone sounds bored…” Meanwhile, the demystification of Bowie continued. TV and radio appearances showcased droll, chatty, New Wave Dave. During a return match with The Daily Express, Jean Rook was amazed at the transformation from three years earlier, when Bowie had been “chalk-skinned, bloodless and apparently dying, if not undead. He looked like a cross between a stick insect and Dracula.” This time, a beaming, tweedily dressed Bowie reminded Rook of “Edward before he met Mrs Simpson… interviewing him is like coming across a daisy in hell.”

During his last months in Berlin, Bowie sensed an ugly new mood in the city. His local Turkish café was smashed up by neo-Nazis, and the owners attacked. Bowie began fretting about whether this was any longer a suitable place to bring up Joe, who was now in his father’s custody. Fascism may not have attracted Bowie to Berlin, but it was clearly a factor in his decision to leave.

By the time he completed Lodger in New York, Bowie’s Berlin therapy session was over. He moved into a Manhattan loft in spring ’79, plugging back into mainstream art-rock currents. He recorded and performed with John Cale and Blondie’s Jimmy Destri, attended shows by Talking Heads, Nico and The Clash.

He also began preparations to storm the post-punk high ground with his next album, Scary Monsters. Like Berlin, New York was an edgy melting pot of art and sleaze, music and sex. But it was also a fresh start, the next chapter, a blank page. A new career in a new town. “I had not intended to leave Berlin, I just drifted away,” Bowie now says. “Maybe I was getting better. It was an irreplaceable, unmissable experience and probably the happiest time in my life up until that point. Coco, Jim and I had so many great times… I just can’t express the feeling of freedom I felt there.”

With a quarter century of hindsight, Bowie eulogises his Berlin trilogy with a twinge of poetic nostalgia for the spooked chemistry and demonic depths which shaped them. “Tony, Brian and I created a powerful, anguished, sometimes euphoric language of sounds,” he says. “In some ways, sadly, they captured, unlike anything else in that time, a sense of yearning for a future that we all knew would never come to pass. It is some of the best work that the three of us have ever done.

“Nothing else sounded like those albums. Nothing else came close. If I never made another album it really wouldn’t matter now, my complete being is within those three. They are my DNA.”