"My complete being is within those three albums." Rob Hughes and Stephen Dalton uncover the complete story of Bowie's life-saving escape to Berlin. How he turned Iggy Pop into a health freak, embraced Brian Eno's "oblique strategies", documented Tony Visconti's indiscretions, and made a fearless and...

Bowie’s headlong rush into Trans Europe Excess actually began in Hollywood in the early part of 1975. Residing at North Doheny Drive in Bel Air, after a disastrous move from New York, the artist formerly known as David Jones began a crazed downward spiral into rock’n’roll damnation. Amid the detritus of an ugly split with management company MainMan, the gradual dissolution of his marriage and mushrooming hordes of pushers and hangers-on, an increasingly fragile Bowie started to implode.

Fuelled by lack of sleep and a raging appetite for what wife Angie described as “fat packages of best Peruvian flake”, Bowie became obsessed with the Kaballah and magick. Snow-blinded by cocaine, he convinced himself that two female fans wanted his sperm for impregnation on the Witches’ Sabbath, thus bringing the spawn of Satan into the world. He later explained, “There was something horrible permeating the air in LA in those days. The stench of Manson and the Sharon Tate murders…”

His days were spent scrawling huge pentagrams on the walls, storing his urine in the fridge to protect him from spells, sculpting vast monoliths in front of the TV and looking for coded messages in Rolling Stones album sleeves. Most terrifying of all was the exorcism of his swimming pool, the waters churning and boiling until an image of the devil was seared into the bottom of the pool. “I drew gateways into different dimensions,” Bowie has said, “and I’m quite sure that, for myself, I really walked into other worlds and saw what was on the other side.”

Besides cocaine, the exiled star lived on a diet of peppers and milk, the curtains closed as he “didn’t want the sun spoiling the vibe of eternal now”. A walking skeleton, he was spoon-fed ice-cream just to maintain his weight. David Bowie was alive, but only just, and very unwell.

“I blew my nose one day and half my brains came out,” he would later recount.

John Lennon and Elton John visited and became convinced that Bowie was close to death. He told friends his phone was bugged and he was being tailed. At the Grammies, Aretha Franklin refused to shake his hand, quipping, “I’m so happy, I could even kiss David Bowie,” as she accepted her award. Even during the subsequent LA sessions for Station To Station, Bowie burned black candles to dispel “unwanted visitors” who’d come over from the other side. To make matters worse, he was falling out bitterly with his latest manager, Michael Lippman, after just a few months.

The grim irony of it all was that Bowie was now enjoying huge success in a land that had proved naggingly elusive for most Brit-rockers to crack. Young Americans had been huge, spawning a US Number 1 single in Fame. His vampiric visage was plastered across every entertainment weekly, and he became one of the first white artists ever to appear on ABC’s prestigious Soul Train. He was also about to make his fêted acting debut in Nic Roeg’s surreal sci-fi flick, The Man Who Fell To Earth. Station To Station would be another smash, eventually hitting Number 3 in the US. But by then, Bowie would be long gone and past caring.

Bowie was so addled during the Station To Station sessions in late ’75, he barely remembers them: “I know it was in LA because I’ve read it was,” he said recently. But it was on this LP that he began to create the brave new world that would lead him to Berlin and, eventually, to sanity. Homesick and bored with the MOR “plastic soul” of his Young Americans phase, Bowie became spellbound with the Teutonic electronica of Kraftwerk and Neu!.

“It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine,” Bowie growled on Station To Station’s title track. Though still infused with US R’n’B, this shuddering rock juggernaut explicitly signposted his new direction: “The European canon is here,” he shrieked over steam-driven, Krautrock-leaning machine rhythms. But any sonic similarities with Kraftwerk’s 1977 classic Trans-Europe Express were coincidental. “Station To Station preceded Trans-Europe Express by quite some time,” says Bowie, speaking exclusively to Uncut in January 2001, arguing that his synthetic fusion of R’n’B and electronica was poles apart from Kraftwerk’s ordered machine symphonies. But he does salute Kraftwerk’s “determination to stand apart from stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music.”

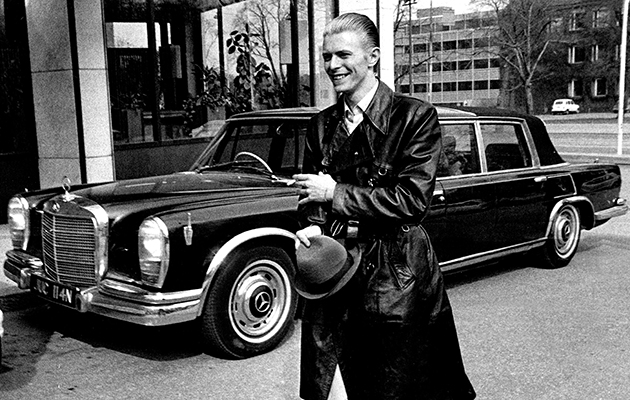

Bowie certainly demonstrated his fondness for Kraftwerk on his White Light [Isolar] tour in 1976, using tapes of their music to set the pre-show mood. Iggy Pop was a permanent fixture on the tour, having discharged himself from UCLA’s Neuro Psychological Institute and had made a pact with Bowie to kick drugs. They were chemical brothers, overdosing on America, rushing headlong into Europe’s embrace. Ironically, both would be arrested on the tour’s East Coast leg for possession of cannabis. “Rest assured the stuff was not mine,” Bowie snapped a few months later. “I can’t say much more, but it did belong to others in the room that we were busted in. Bloody potheads. What a dreadful irony, me popped for grass. The stuff sickens me. I haven’t touched it in a decade.”