Ditching the intricately staged theatrics of previous stage shows, the White Light tour was a Euro-fixated extravaganza, with Bowie steeped in banks of white light, offset with harsh black backdrops. Inspired by German Expressionist cinema, Brechtian theatre and the photography of Man Ray, these live shows cast Bowie as his last and cruellest “character” – The Thin White Duke. Uniformed in pleated black pants, waistcoat and white shirt, fire-blonde hair scraped back, Bowie calls the Duke “a very Aryan, fascist type – a would-be romantic with absolutely no emotion.”

The description proved chillingly apt, as Bowie’s obsession with occultism and Germanic culture had evolved into an unhealthy fascination with The Third Reich, Arthurian Grail mythology, and Hitler himself. He gave unguarded interviews warning of a fascist backlash and sneering that “people aren’t very bright, you know. They say they want freedom, but when they get the chance, they pass up Nietzsche and choose Hitler, because he’d march into a room to speak, and music and lights would come on at strategic moments. It was rather like a rock’n’roll concert.”

While the British press fiercely debated Bowie’s fascist fixation, the White Light tour rumbled on towards Europe. Bowie emptied his Hollywood house during a three-night residency in LA, packing the contents off to the Clos des Mésanges, the new home that his wife Angie had found in Blonay, Switzerland. The backstage guests in LA included Christopher Isherwood – the original Berlin-exiled Brit whose writings inspired the film Cabaret. At the same shows, Bowie dropped hints about his future direction: “I quite like Eno. I’d like him to be in Iggy’s band. How gauche. No, actually, I’m getting Iggy an all black-band of ex-basketball players…”

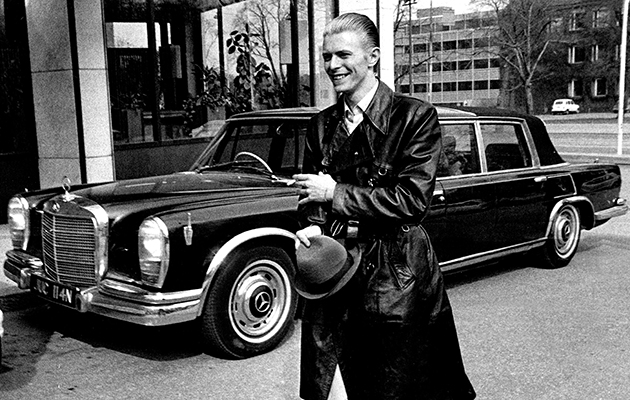

In April, the White Light tour enjoyed an extended layover in Berlin. Bowie and Iggy were smitten, sampling the city’s clubs and transvestite bars. Tour photographer Andrew Kent recalls, “We went through Checkpoint Charlie and drove around East Berlin in David’s limo. It was the President of Sierra Leone’s old Mercedes 600 and it had one of those windows where you could stand and wave to the crowd. He had a great driver, Tony Mascia, and we went out at night and drove real fast. David and Iggy loved it, they were out all the time.”

Following the Zurich show on April 17, with a week before the tour resumed, train tickets were arranged to take Bowie, his longtime PA Coco Schwab, Iggy, Andrew Kent and a handful of others up to Helsinki via Warsaw and Moscow. It was an eventful trip.

In Brest, on the Polish-Russian border, they were detained while books on Goebbels and Albert Speer were seized. Bowie claimed they were “research” materials for a film he was planning about Hitler’s propaganda minister.

“Oh man, we didn’t know what was going to happen,” recalls Kent. “The train stops and an albino KGB man comes in! He takes us off the train, we go into this huge Russian inspection place and an interpreter comes up and says, ‘We weren’t expecting you.’ We were all separated. Iggy and David got strip-searched. I think they took some books away, that was all. I don’t know what they took from David, but they took a Playboy away from me.”

Further complications lay ahead. “They said they’d have somebody to meet us in Moscow,” says Kent, who organised tickets and transit visas. “There was nobody there. So when we got off the train we hired a military truck to take us to the Metropole hotel. We went to Red Square and the GUM department store, then back to the Metropole for caviar, then we met the next train in a different train station and left. We were in Moscow for seven hours, that’s where all those pictures came from. And then in Helsinki they thought we were lost, as the train schedules were wrong. There were headlines saying we were lost in Russia.”

As reports of this incident filtered back to Britain, plus further inflammatory comments about Hitler from a Swedish press conference, concern about Bowie’s political leanings shook the UK music press. It was in this incendiary climate that Bowie finally arrived on home soil at Victoria Station in his open-topped Mercedes in May 1976. Here the notorious “heil and farewell” incident took place, a stiff-armed wave that no-one present took to be a Nazi salute. Only in subsequent press reports did Bowie’s gesture turn sinister. “That did not happen,” Bowie later fumed. “I just waved. Believe me. On the life of my child, I waved. And the bastard caught me. In mid-wave, man… as if I’d be foolish enough to pull a stunt like that. I died when I saw the photo.”

According to one biographer, however, Bowie threw a genuine Nazi salute in Berlin for photographer Andrew Kent on the promise that the picture would never be made public. “I don’t want to talk about it,” says Kent. “I never felt David was a Nazi sympathiser. I’m Jewish, so if anybody would be sensitive to that and have bad feelings… I just think it was what I’d call an adolescent attraction.”

Whether or not he struck the pose, Bowie’s interest in fascism was clearly never a serious flirtation. He’s spent twenty-five years explaining and apologising for the “glib theatrical observations” he made in ’75 and ’76. His band at the time, mostly black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers, never took the comments seriously. Eno now dismisses them as pure posturing. Only the boneheads of the NF, who praised Bowie’s “Aryan” sound in their literature, and the equally dim FBI, who reportedly listed Bowie as an “apparent Nazi sympathiser”, could miss the illogical irony of his public statements.

What is clear is that Bowie’s mental state was wracked and ravaged in the mid-’70s. Before the White Light shows at Wembley in May, he protested to Fleet Street journalist Jean Rook that The Thin White Duke was not so much a rock’n’roll Hitler as “pure clown… the eternal clown putting over the great sadness of 1976.” Rook noted that Bowie “looks terribly ill. Thin as a stick insect. And corpse pale, as if his lifeblood had all run up into his flaming hair.”